Content

- Recent digs in T.N.’s Tenkasi reveal presence of Iron Age culture

- The mountains mourn

- Do cash transfers build women’s agency?

- Case Study: Natural farming gains traction in Himachal

- The grain of ethanol production

- Quantum leap by Indian researchers in boosting digital security

- In Morocco, Madagascar now: what unites ‘Gen Z’ protests across countries

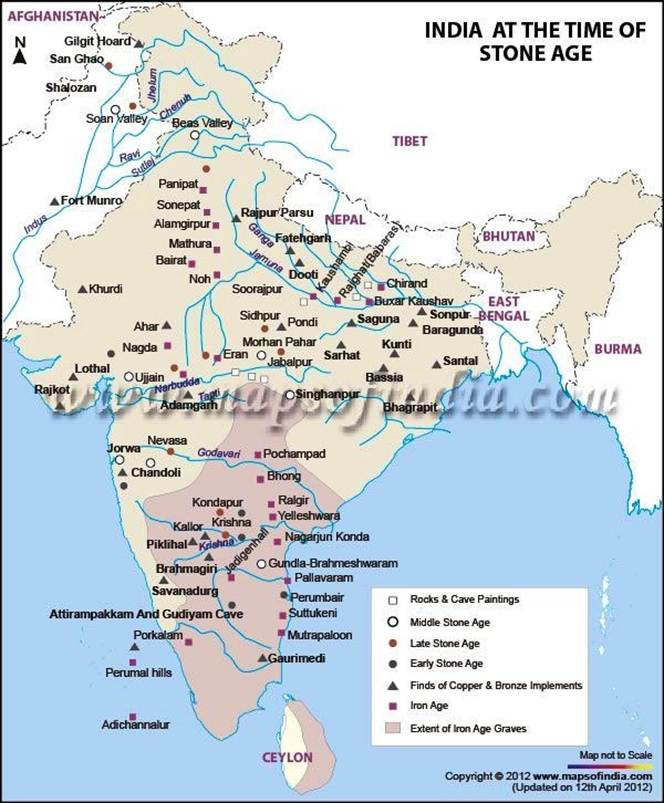

Recent digs in T.N.’s Tenkasi reveal presence of Iron Age culture

Why in News

- The Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology (TNSDA) conducted its first season of excavations at Thirumalapuram in Tenkasi district.

- Excavations revealed Iron Age cultural remains near the Western Ghats in Tamil Nadu.

- Discovery includes urn burials, a stone slab chamber, and various ceramics, marking a first-of-its-kind finding in the state.

Relevance

- GS 1 – Ancient history : Iron Age in South India, archaeological methodology.

Basic Overview

- Location: Thirumalapuram, ~10 km northwest of the present-day village, between two seasonal streams from the Western Ghats.

- Site Area: Approximately 35 acres.

- Dating: Tentatively dated to early to mid-3rd millennium BCE (Iron Age).

- Excavation Method: 37 trenches dug during the first season.

Key Findings

- Burial Structures

- A rectangular chamber constructed with 35 stone slabs, filled with cobblestones up to 1.5 m depth.

- Contains urn burials, unique in Tamil Nadu.

- Ceramics

- Variety of pottery found: black-and-red ware, black ware, black-slipped ware, red ware, red-slipped ware.

- Some ceramics featured white-painted designs, a unique feature for the region.

- Grave Goods

- Pottery included symbols on urns, considered among the most striking discoveries.

- Grave goods reflect ritualistic and cultural practices.

- Comparison with Other Sites

- Similar symbols and ceramic types seen in Adichanallur, Sivagalai, Thulukkarpatti, Korkai.

- Helps in understanding regional continuity and spread of Iron Age culture in Tamil Nadu.

Historical and Archaeological Significance

- First-of-its-kind discovery in Tamil Nadu: Urn burials with stone slab chambers were not previously reported in the state.

- Indicates Iron Age cultural presence close to the Western Ghats, expanding knowledge beyond coastal or plains-based settlements.

- Helps reconstruct funerary practices, ritualistic life, and material culture of early communities in southern India.

- Adds to the body of evidence on ceramic technology, burial practices, and symbolism in South Indian Iron Age archaeology.

Scientific and Methodological Insights

- Excavations employed systematic trenching and scientific analyses.

- Artifact study allows chronological placement, typology classification, and comparative analysis with other Iron Age sites.

- Provides a baseline for further multidisciplinary studies, including geoarchaeology, archaeobotany, and material science.

Broader Implications

- Cultural: Reveals regional variation in Iron Age practices and expands understanding of social hierarchies and ritual practices.

- Tourism & Heritage: Potential for archaeological tourism and heritage awareness in Tenkasi.

- Academic: Opens avenues for research on Iron Age trade, migration, and technology in peninsular India.

- Preservation: Emphasizes the importance of protecting newly discovered archaeological sites from encroachment or looting.

Value Addition

Chronology & Periodization

- Iron Age in South India: ~1200 BCE – 300 BCE (regional variations exist).

- Characterized by the introduction of iron tools, agriculture intensification, and settled village life.

- Coexisted with megalithic practices, including elaborate burials, indicating complex social structures.

Settlement Patterns

- Location: Predominantly near rivers, fertile plains, and foothills of the Western Ghats.

- Sites include Adichanallur, Sivagalai, Korkai, Thirumalapuram, Thulukkarpatti, T. Kallupatti.

- Suggests agriculture-based economy, supplemented by pastoralism and trade.

Material Culture

- Pottery: Black-and-red ware (BRW), black-slipped ware, red-slipped ware, coarse red ware; often decorated with white-painted motifs.

- Iron Tools: Axes, chisels, sickles, indicative of farming, woodwork, and craft specialization.

- Symbolic Artefacts: Ceramics with symbols on urns reflect ritual and religious symbolism, possibly linked to ancestor worship.

Burial & Funerary Practices

- Megalithic urn burials: Stone slab chambers, cobblestone-filled graves, cist burials.

- Contained urns with human remains, pottery, and grave goods.

- Indicates belief in life after death and hierarchical social structures.

- Regional uniqueness: Thirumalapuram urn burials are the first slab-chamber type in Tamil Nadu, unlike earlier southern urn burials.

Socio-Economic Insights

- Agriculture: Iron tools enabled intensification of cultivation, supporting population growth.

- Trade & Craft: Evidence of beads, metal ornaments, and distinctive ceramics suggests local and inter-regional trade.

- Social Stratification: Variation in grave goods implies emerging hierarchies and differentiated social status.

Cultural & Ritual Aspects

- Symbols on urns indicate early literacy of symbols or proto-writing systems, possibly for clan or identity markers.

- Ancestor worship and ceremonial burial rituals show complex belief systems.

- Continuity with later Tamil culture and religious practices, e.g., reverence for hills and rivers.

The mountains mourn

Why in News

- Torrential rainfall on the night of October 4–5, 2025 triggered over 110 major landslides in Darjeeling district and other parts of north Bengal.

- At least 32 dead, 40 injured, thousands stranded, with many missing.

- Areas like Mirik, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Jalpaiguri, and Alipurduar were severely affected.

- The disaster coincided with Dashain festival, during which many families had gathered for celebrations, worsening human impact.

Relevance

- GS 1 – Geography: Landslide-prone Himalayan terrain, hydrology of Teesta and Balason rivers, impact of rainfall on soil stability.

- GS 3 – Disaster Management: Floods, landslides, NDRF operations, disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies.

- GS 3 – Environment & Climate Change: Extreme rainfall, climate change impact, hydropower projects and river management.

Basic Overview

- Rainfall: ~261 mm in 12 hours caused soil instability, river overflow, and landslides.

- Geography: Darjeeling and Mirik are hilly regions cradled between Western Himalayan ranges and alpine forests.

- Infrastructure Damage: Roads vanished under mud; Balason river iron bridge collapsed, temporarily cutting off connectivity.

- Tourism Impact: Mirik and surrounding areas rely heavily on tourism, now disrupted, affecting livelihoods.

Human Tragedy & Social Impact

- Personal accounts reveal loss of children and relatives due to sudden landslides during sleep.

- Many families lost entire households, highlighting vulnerability during extreme weather.

- Psychological trauma and grief compounded by the festival season, which is usually associated with celebration.

- Community displacement: Families moved to temporary shelters like Dudhia community hall.

Geological & Environmental Factors

- Terrain: Steep slopes, unstable soil, and heavy rainfall combine to create high landslide risk in Darjeeling hills.

- Hydropower Projects: Tala hydropower dam and other projects contributed to flooding after dam gates failed to open.

- River Systems: Teesta and Balason rivers played a role in rapid water flow, contributing to soil erosion and infrastructure collapse.

- Climate Dimension: Increased frequency of extreme rainfall events linked to climate change may exacerbate such disasters.

Economic & Livelihood Impact

- Tourism-dependent communities lost income due to road closures and suspended travel to hill destinations like Mirik and Sandakphu.

- Infrastructure damage disrupted local trade and access to essential services.

- Additional costs for restoration, temporary shelters, and compensation added to government expenditure.

Humanitarian & Social Implications

- Highlighted vulnerability of hilly populations to flash floods and landslides.

- Exposed the need for early warning systems, flood forecasting, and community awareness.

- Emphasized importance of resilient infrastructure in disaster-prone regions.

- Psychological impact on children, families, and displaced populations.

Broader Implications

- Governance: Need for proactive disaster management and coordination between central, state, and local bodies.

- Environment & Climate Policy: Importance of sustainable land use, forest cover maintenance, and hydropower regulation.

- Disaster Preparedness: Integration of early warning systems, evacuation plans, and local community training.

- Socio-Economic Resilience: Strengthening tourism, agriculture, and infrastructure to withstand natural disasters.

Landslide Basics

Definition & Types

- Landslide: Downward and outward movement of rock, soil, or debris on slopes due to gravity.

- Types of Landslides:

- Rockfalls: Sudden free-fall of rocks from steep cliffs.

- Debris Flows: Rapid movement of loose soil, rocks, and water.

- Slumps: Rotational sliding of soil along a curved surface.

- Creeps: Very slow downward movement of soil or rock.

- Complex Landslides: Combination of types (e.g., slump followed by debris flow).

Causes of Landslides

A. Natural Causes

- Heavy rainfall / Snowmelt: Saturates soil, reduces cohesion.

- Earthquakes: Trigger slope failure in hilly regions.

- Volcanic activity: Lava and ash destabilize slopes.

- Steep slopes and unstable geology: Common in Himalayas, Western Ghats.

B. Anthropogenic / Human-Induced Causes

- Deforestation: Removes root structures stabilizing slopes.

- Construction & urbanization: Roads, buildings, and terrace cuts destabilize slopes.

- Mining / Hydropower projects: Excavation weakens natural slope stability.

- Poor drainage & irrigation: Waterlogging increases pore pressure in soil.

Regions Prone to Landslides in India

- Himalayas: Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Darjeeling, Sikkim.

- North-Eastern Hills: Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya.

- Western Ghats: Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra.

- Other Regions: Nilgiris (Tamil Nadu), parts of Andaman & Nicobar Islands.

Do cash transfers build women’s agency?

Why in News

- Despite near-universal Jan Dhan accounts and rise of Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) schemes, women’s economic agency in India remains incomplete.

- Recent initiatives like Bihar’s Mukhyamantri Mahila Rojgar Yojana (2025) aim to provide seed capital to 75 lakh women for self-employment.

- The issue has policy and socio-political dimensions: cash transfers act as both welfare instruments and electoral strategies.

Relevance

- GS 1 – Social Issues: Women’s empowerment, gender inequality, digital divide.

- GS 2 – Governance: DBT schemes, JAM trinity, policy implementation, and evaluation.

- GS 2 – Social Justice: Access to resources, property rights, social inclusion.

- GS 3 – Economy: Financial inclusion, self-employment, women-led entrepreneurship, impact on household welfare.

Basic Overview

- Goal: Move beyond placing money in women’s accounts to genuine financial empowerment.

- Current Status:

- 56 crore Jan Dhan accounts opened; women hold 55.7%.

- Despite 38 crore RuPay cards issued, women’s usage of debit cards and digital payments lags behind men.

- Challenges: Low digital literacy, limited mobile phone access (19% less than men), patriarchal norms, distance from banks, and lack of privacy.

Key Issues & Barriers

1. Financial Access vs Agency

- Accounts exist but are often dormant or used only to withdraw cash transfers.

- Women rarely control assets, take loans, or make independent financial decisions.

2. Digital Divide

- Women’s low mobile phone ownership restricts access to digital banking.

- Reliance on shared devices erodes privacy, autonomy, and independent decision-making.

3. Socio-Cultural Constraints

- Patriarchal norms often restrict women’s financial participation.

- Social attitudes limit women from leveraging their bank accounts, savings, or credit opportunities.

4. Structural & Policy Gaps

- Less than 10% of banking correspondents are women, reducing trust and accessibility.

- Lack of tailored financial products for women’s informal, seasonal, or sporadic incomes.

- Insufficient financial and digital literacy programs.

Recent Policy Initiatives

- Bihar’s Mukhyamantri Mahila Rojgar Yojana: ₹10,000 seed capital for self-employment, with potential additional ₹2 lakh support.

- Other women-focused DBT programs include:

- Karnataka: Gruha Lakshmi

- West Bengal: Lakshmir Bhandar

- Madhya Pradesh: Ladli Behna

- Telangana: Mahalakshmi

- Programs rely on JAM trinity (Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, Mobile) for direct and transparent delivery.

Path to Economic Empowerment

1. Asset Ownership

- Women must have tangible control over land, property, or business assets to leverage credit and sustain enterprises.

2. Digital & Financial Literacy

- Providing subsidized smartphones, affordable data, and training.

- Establish community-based advisory networks (digital banking sakhis, WhatsApp/UPI groups).

3. Agency-Building

- Beyond receiving money, women should be able to:

- Grow and reinvest funds.

- Engage with markets and participate in new forms of commerce.

- Exercise decision-making in household and community economic matters.

4. Institutional Support

- Co-create financial products reflecting women’s informal and seasonal income patterns.

- Expand female banking agents to enhance trust and access.

Socio-Economic & Political Implications

- Household Welfare: Increased income in a woman’s name improves child and elderly outcomes.

- Social Justice: Strengthens women’s role as economic actors, not just welfare recipients.

- Political Economy: Cash transfer schemes often have electoral significance, influencing political participation and accountability.

- Macro-Level: Empowering women financially can boost entrepreneurship, market participation, and inclusive growth.

Case Study : Natural farming gains traction in Himachal

Why in News

- Himachal Pradesh farmers are increasingly adopting chemical-free natural farming, supported by state policies and incentives.

- The push aligns with India’s broader national focus on sustainable and chemical-free agriculture.

- Farmers are benefiting from higher yields, better prices, and reduced input dependence, creating both economic and environmental advantages.

Relevance

- GS 3 – Agriculture: Natural farming, MSP, productivity, input management, organic agriculture.

- GS 3 – Environment & Biodiversity: Soil conservation, reduction in chemical inputs, eco-friendly practices.

- GS 2 – Governance: State-supported schemes, policy interventions, implementation of PK3Y.

- GS 3 – Economy: Market linkages, price support, rural income enhancement.

- GS 1 – Society: Women’s participation in agriculture, livelihood improvement.

Basic Overview

- Natural/Organic Farming: Agricultural practices without synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, relying on farm-produced inputs and ecological balance.

- Key Government Support:

- Prakritik Kheti Khushhal Kisan Yojana (PK3Y): Launched 7 years ago to promote natural farming in Himachal Pradesh.

- Minimum Support Prices (MSP): Turmeric ₹90/kg, wheat ₹60/kg, maize ₹40/kg.

- Training & Certification: Farmers are trained and certified via CETA–ARA–NF (Certified Evaluation Tool for Agriculture – Natural Farming).

Current Adoption & Outcomes

- Over 3.06 lakh farmers trained, with 2.22 lakh practicing partially or fully across 38,437 hectares.

- Farmers report:

- Higher profits: E.g., turmeric price rose from ₹60/kg (local market) to ₹90/kg (government procurement).

- Health benefits: Reduced chemical exposure reduces farmer illness.

- Independence: Farmers produce their own inputs, lowering market dependence.

- Women farmers are increasingly participating, expanding wheat and turmeric cultivation.

Drivers of Adoption

- Economic Incentives: MSP support encourages market creation for natural produce.

- Training & Certification: PK3Y provides knowledge and credibility for natural farming practices.

- Health & Environmental Awareness: Chemical-free methods protect soil health, biodiversity, and human health.

- Government Backing: Policies create a structured ecosystem including procurement, pricing, and extension services.

Benefits of Natural Farming

A. Economic

- Higher yield and better prices due to government support.

- Reduced dependency on chemical inputs, lowering production costs.

- Opens market for premium, organic products nationally and potentially internationally.

B. Environmental

- Enhances soil fertility and biodiversity.

- Reduces groundwater contamination and chemical runoff.

- Promotes long-term sustainability of hill agriculture.

C. Social

- Empowers women farmers and smallholders.

- Builds community knowledge networks and reduces dependency on corporate agro-inputs.

Challenges

- Initial yield fluctuations during transition from chemical to natural farming.

- Need for efficient marketing and supply chains to prevent price disparities.

- Labor-intensive practices require skill and training.

- Limited awareness and adoption in remote villages due to digital and extension service gaps.

Policy & Institutional Support

- PK3Y (Prakritik Kheti Khushhal Kisan Yojana): Training, input support, MSP, and market integration.

- CETA–ARA–NF Certification: Validates natural farming practices and encourages market trust.

- State Government Procurement: Government agencies procure at higher prices to incentivize adoption.

Broader Implications

- Sustainability: Demonstrates a model for eco-friendly hill agriculture in India.

- Health: Chemical-free produce is safer for consumers and reduces occupational health hazards.

- Replication Potential: Successful model can be adapted for other hill states and tribal regions.

- Women Empowerment: Promotes economic participation and decision-making among rural women farmers.

The grain of ethanol production

Why in News

- India’s ethanol blending programme, initially meant to support sugarcane growers, has increasingly benefited standalone grain-based ethanol producers.

- Investment of ₹40,000 crore in ethanol distilleries has shifted the focus from sugarcane to grains like maize and surplus rice, due to sugar shortages and policy incentives.

- Ethanol blending in petrol aims to reduce oil import dependence, support farmers, and promote cleaner fuels.

Relevance

- GS 3 – Economy: Ethanol blending programme, agro-industrial investment, rural economy, food vs fuel policy.

- GS 3 – Agriculture: Crop diversification, sugarcane economics, grain utilization, government procurement.

- GS 3 – Energy & Environment: Biofuels, renewable energy, emission reduction, energy security.

- GS 2 – Governance & Policy: Implementation of National Biofuel Policy, coordination between OMCs, distilleries, and agricultural stakeholders.

Basic Overview

- Ethanol Blending Programme (EBP): Launched to blend ethanol in petrol, initially targeting sugar mills to provide extra revenue via ethanol production.

- Feedstock Sources:

- Sugarcane (C-heavy molasses, B-heavy molasses, cane juice/syrup)

- Grains (maize, surplus/damaged rice from FCI)

- Government Incentives: Higher prices for ethanol from B-heavy molasses, cane juice/syrup, and grains; excise-duty exemptions for grain-based ethanol.

- Production Mechanism:

- Molasses/cane juice: Sucrose fermentation → ethanol

- Grain: Starch conversion → sugar → fermentation → ethanol

Trends in Ethanol Production

- Supply Increase: Ethanol supplied to OMCs rose from 38 crore litres (2013-14) to 189 crore litres (2018-19).

- Blending Ratio: Increased from 1.6% to over 4% in petrol.

- Grain-Based Ethanol Dominance:

- 2023-24: 672.4 crore litres procured; <40% from sugarcane, >60% from grains.

- 2024-25: 920 crore litres requirement projected; 520 crore litres from grains, 400 crore from sugarcane-based feedstock.

- Maize contributes the majority of grain-based ethanol (~420 crore litres).

Reasons for Grain Dominance

- Sugar Shortage: Plummeting sugarcane output (423.8 lakh tonnes in 2023-24; 331 lakh tonnes projected in 2024-25) limits sugarcane ethanol production.

- Policy Neutrality: Government procurement policy does not distinguish feedstock, so distilleries can supply grains or sugarcane.

- Higher Returns: Ethanol price (₹71–86/litre) exceeds market value of rice, maize, or cane juice.

Economic & Policy Implications

- Investment & Capacity: 499 distilleries with ₹40,000 crore investment, annual capacity 1,822 crore litres; OMCs procurement limited to 1,050 crore litres → potential overcapacity.

- Food vs Fuel Debate: Grain-based ethanol uses maize and rice that could feed humans or livestock, raising concerns about food security.

- Supply Constraints: Ethanol from sugarcane is capped by domestic sugar consumption, while grain ethanol can expand but may affect feed prices for poultry/livestock.

- Market Dynamics: Potential to create new markets for surplus grain but requires careful balancing of agricultural production and domestic consumption.

Wider Implications

A. Energy & Environment

- Supports National Biofuel Policy and petrol blending targets (20%), reducing fossil fuel dependence.

- Ethanol use reduces vehicular emissions and greenhouse gases.

B. Agricultural

- Provides an alternative revenue stream for farmers, especially in surplus grain-producing states (Punjab, Haryana, Bihar, MP, UP, Maharashtra).

- Could influence crop choice and production patterns, with more maize/rice diverted to ethanol.

C. Economic

- Encourages private investment in distilleries and rural industrial growth.

- Risk of oversupply and price volatility if ethanol output exceeds OMCs’ procurement capacity.

D. Policy Challenges

- Need to balance sugarcane, grain, and food security interests.

- Must ensure efficient procurement, blending, and storage infrastructure.

- Managing ethanol pricing and feedstock allocation to avoid inflationary pressures on food and livestock feed.

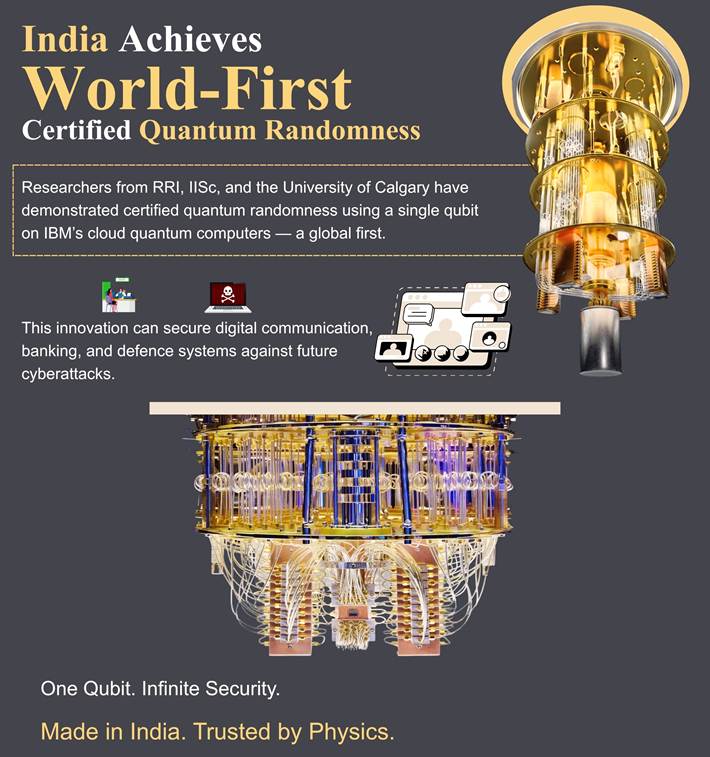

Quantum leap by Indian researchers in boosting digital security

Why in News

- Indian researchers at Raman Research Institute, Bengaluru, led by Urbasi Sinha, have developed quantum techniques to generate and certify truly random numbers.

- The breakthrough has major implications for digital security, potentially enabling hack-proof encryption.

- It is a globally significant achievement under India’s National Quantum Mission.

Relevance

- GS 3 – Science & Technology: Quantum computing, quantum cryptography, cybersecurity, National Quantum Mission.

- GS 3 – Security: Digital security, encryption, quantum-proof technologies.

- GS 2 – Governance: Government support in quantum research and technology commercialization.

- GS 3 – Economy & Industry: Potential for startups, innovation, and technology exports in quantum security.

Basics

- Random Numbers in Digital Security:

- Foundation of encryption, passwords, and secure authentication systems.

- Must be truly random (not predictable) for high security.

- Pseudorandom Numbers:

- Currently used in computers, generated via algorithms.

- Adequate for today’s security but vulnerable to quantum computing attacks.

- Quantum Random Numbers:

- Derived from inherently random quantum processes (e.g., electron behavior, photon states).

- Device-independent methods ensure numbers cannot be predicted or manipulated.

Key Scientific Concepts

- Quantum Random Number Generation (QRNG):

- Uses quantum phenomena such as superposition and entanglement.

- Example: Measurement of electrons/photons to produce random sequences of 0s and 1s.

- Certification Challenge:

- Even quantum devices may be hacked or malfunction, so output must be certifiable as truly random.

- Certification ensures randomness is not from device fault or external manipulation.

- Entanglement & Bell’s Inequality:

- Two entangled particles behave as substitutes across distance.

- If measurement results violate Bell’s inequality, the randomness is quantum in origin.

- Leggett-Garg Inequality:

- Used to certify true randomness at the single-particle level.

- 2024: RRI generated random numbers violating this inequality in a lab setting.

The Breakthrough

- First demonstration of device-independent QRNG using a commercially available quantum computer.

- Significance:

- Moves beyond controlled lab experiments to real-world noisy environments.

- Enhances practical applicability of quantum random numbers for digital security.

- Potential Applications:

- Hack-proof encryption

- Secure communication channels

- Authentication systems resistant to quantum attacks

- Strategic & Commercial Implications:

- Boosts India’s capabilities in quantum technologies.

- Opens avenues for startups and research commercialization.

- Reinforces India’s position in the global quantum security landscape.

Challenges Ahead

- Scaling up commercial applications while ensuring security in real-world conditions.

- Continued research and funding required for robust device-independent QRNG systems.

- Integration into national digital security infrastructure and financial networks.

In Morocco, Madagascar now: what unites ‘Gen Z’ protests across countries

Why in News

- Youth-led ‘Gen Z protests’ have erupted in Morocco and Madagascar, following earlier similar movements in Indonesia, Nepal, and the Philippines.

- These are social media–driven mass agitations centered around inequality, poor governance, and quality-of-life issues, reflecting a global pattern of youth disillusionment in developing economies.

Relevance

- GS 2: Governance, accountability, political participation, comparative politics.

- GS 1 (Society): Youth aspirations, social change, inequality.

Basic Context

- Gen Z refers to the generation born between mid-1990s and early 2010s, now in their 20s or early 30s.

- They are digitally connected, socially conscious, and politically assertive, often using online platforms like Discord, TikTok, and Facebook for mobilisation.

- These protests represent a new form of political participation, less reliant on formal organisations and more driven by networked activism.

Triggers and Contexts

1. Morocco

- Trigger: Death of a young woman during childbirth in a public hospital (Agadir, Sept 2024).

- Symbolism: Protesters contrasted poor healthcare with billions spent on FIFA World Cup 2030 infrastructure.

- Slogan: “Stadiums are here, but where are the hospitals?”

- Organisers: Collective called Gen Z 212 (country code for Morocco) using Discord for coordination.

- Socioeconomic context:

- Unemployment (15–24 yrs): 36%

- Per capita GDP (2024): USD 3,993 (global avg: > USD 13,000)

- >50% population under 35; frustration with inequality and elite privilege.

- Political backdrop: Constitutional monarchy; visible inequality between ruling elite and youth masses.

2. Madagascar

- Trigger: Government repression of youth protests (Sept 2024) leading to 20+ deaths.

- Escalation: Youth-led movement (Gen Z Madagascar) evolved into a wider anti-establishment uprising, leading to President Andry Rajoelina’s resignation.

- Organisation: Initially youth movements on Facebook & TikTok, later supported by civil society groups.

- Economic distress:

- Per capita income declined 45% since independence (1960–2020).

- Widespread poverty and public anger at elite capture of resources.

Common Threads Across Gen Z Movements

- Digital mobilisation: Social media as the main tool for organisation and message amplification.

- Economic frustration: Youth unemployment, inequality, and declining purchasing power.

- Perceived elite capture: Anger against “nepo kids” (nepotism, privilege, and dynastic elites) — seen in Nepal, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

- Quality-of-life concerns: Health, education, job security, and state accountability.

- Erosion of trust: Young citizens view traditional political structures as unresponsive and corrupt.

- Short-lived intensity: Movements gain traction rapidly but often fizzle out due to lack of long-term coalition building.

Structural Causes

- Economic:

- Shrinking industrial jobs due to automation and globalisation.

- Middle-income trap in developing economies.

- Inflation and cost-of-living crisis post-pandemic.

- Social:

- Rising educational aspirations unmet by job opportunities.

- Social media exposure magnifies global comparisons and resentment.

- Political:

- Weak democratic accountability; dominance of entrenched elites.

- Repressive state responses erode legitimacy further.

Global Dimensions

- Similar Gen Z uprisings seen in:

- Indonesia (2020–21): Labour law reforms.

- Nepal (2023): Corruption and nepotism.

- Philippines: Inequality and political dynasty protests.

- Reflects a transnational generational shift in political participation, often leaderless but connected online.

Scholarly Insight

- As per Dr. Janjira Sombatpoonsiri (German Institute for Global & Area Studies):

- These movements stem from a “crisis of expectations” — youth promised prosperity through education but facing structural stagnation.

- Social media enables rapid mobilisation but weak organisational endurance, limiting tangible outcomes.

Implications

- Governance Challenge: States must address youth aspirations through inclusive growth and service delivery.

- Political Reforms: Need for democratic responsiveness and youth engagement.

- Security Dimension: Online radicalisation or unrest risk if grievances persist.

- Developmental Focus: Investment in education-to-employment linkages, digital literacy, and job creation.