Content

- The struggle to count women’s labour

- No one talks about the slow emergency of Kolkata smog

The struggle to count women’s labour

Why in News ?

- Recent discourse highlights that women’s unpaid domestic, care, and emotional labour remains structurally invisible and economically undervalued, despite its central role in sustaining households, productivity, and social reproduction.

- A 2023 UN report shows women worldwide spend 2.8× more time than men on unpaid care and domestic work, reinforcing persistent gender inequities in labour recognition and policy design.

Relevance

GS-II | Welfare, Social Justice, Gender & Labour Policy

- Recognition of unpaid care, domestic and emotional labour as a core pillar of social reproduction and economic productivity.

- Highlights policy invisibility, gender bias in labour valuation, and structural inequality in welfare and social-security frameworks.

GS-III | Economy, Inclusive Growth & Human Capital

- Shows how unpaid care work acts as a hidden subsidy to the economy and suppresses female labour-force participation.

- Links GDP-centric accounting bias with undervaluation of non-market work and unequal growth outcomes.

Practice Question

- “Unpaid care and emotional labour constitute the invisible backbone of the economy, yet remain structurally excluded from policy and national accounting.” Discuss with examples. (250 Words)

Basics — What is “Unpaid & Emotional Labour”?

- Unpaid Domestic Labour

Cooking, cleaning, childcare, elderly care, household management — non-market work essential for household functioning. - Care Work / Social Reproduction

Activities that maintain and reproduce the labour force — health, caregiving, nurturing, emotional support. - Emotional & Mental Labour

Managing relationships, conflict mediation, planning, invisible coordination, ensuring social harmony — rarely measured or compensated.

Core Issue: This labour enables the economy to function but is excluded from GDP, budgets, labour law, and social security frameworks.

What the Scholars Argue ?

- Economic systems privilege “productive” paid labour (male-breadwinner bias).

- Care labour is feminised, informalised, and devalued in policy and accounting.

- Biological framing of reproduction hides the social-historical power imbalance in gendered division of labour.

- Separation of production vs. social reproduction maintains women’s subordination.

Analytical takeaway: The invisibility of women’s labour is not accidental — it is structural and ideological.

Structural Causes of Invisibility

- GDP-centric policy bias — only market output counted; unpaid labour excluded.

- Infrastructure > Social Investment — childcare, eldercare, mental health underfunded.

- Male-breadwinner employment priority — reinforces women’s unpaid care role.

- Cultural norms — care framed as “duty” or “love”, not work.

- Lack of labour law coverage & social security — unpaid workers remain unprotected.

Global Evidence — Patchy Legal Recognition

- Bolivia (Art. 338 Constitution) — Home-based work recognised as economic activity, housewives entitled to social security.

- Trinidad & Tobago (Counting Unremunerated Work Act, 1996) — Mandates measurement and valuation of unpaid work by gender.

- Argentina — Pension credits for unpaid care work performed while raising children.

- Gap: Even where unpaid domestic work is recognised, emotional and mental labour remains unacknowledged.

India — Status & Emerging Legal Signals

- No statutory framework recognising unpaid or emotional labour in economic terms.

- Judicial development

- Kannaian Naidu vs Kamsala Ammal (Madras HC, 2023)

- Household and caregiving contribution = indirect contribution to family assets → wife entitled to equal property share.

- Kannaian Naidu vs Kamsala Ammal (Madras HC, 2023)

- Policy challenge: Without redistribution of care responsibilities, unpaid work remains feminised and unequal.

Economic & Social Implications

- Reduces women’s labour-force participation & career mobility.

- Double burden on poor & marginalised women — they sustain reproductive labour for households of others.

- Hidden subsidy to the economy — unpaid care absorbs costs the State/market should bear.

- Inter-generational inequality reproduction — reinforces gender hierarchies.

Data-Backed Insights

- UN (2023): Women perform 2.8× more unpaid care work than men globally.

- In many countries, unpaid care work is estimated to equal 10–39% of GDP equivalents (time-use valuation studies, various economies).

- Time-use surveys consistently show care labour is the single largest block of women’s work hours.

Key Gaps in Current Frameworks

- Fragmented or symbolic recognition; no comprehensive valuation mechanisms.

- Emotional & mental labour completely invisible in law and statistics.

- Limited male participation in household care roles.

- Weak integration of time-use data into budgets and policy design.

Way Forward — Policy & Institutional Reforms

- Time-Use Surveys → Satellite National Accounts for Care Work

Integrate valuation into budgets and policy appraisal. - Social-infrastructure investment — childcare, eldercare, community care, mental-health services.

- Shared-care norms & incentives — parental leave for men, workplace flexibility.

- Legal & social-security recognition — pension credits, recognition of caregiving spells.

- Public discourse shift — recognise emotional labour as economic and social value.

Conclusion

Women’s unpaid, care, and emotional labour sustains households, markets, and social stability, yet remains structurally invisible due to economic accounting biases, gender norms, and policy priorities. Meaningful recognition requires redistribution of care, institutional valuation, social-infrastructure investment, and normative change, moving from symbolic acknowledgment to systemic inclusion in law, budgets, and welfare frameworks.

No one talks about the slow emergency of Kolkata smog

Why in News ?

- Winter 2024–25 air-quality readings in Kolkata showed dangerous, recurring PM2.5 spikes, with AQI repeatedly slipping into the “very poor” category — signalling a slow-moving public-health emergency that receives limited political or policy attention compared to Delhi.

- The editorial highlights how urban smog in Kolkata is normalised, despite health-threatening exposure levels crossing WHO limits multiple times over.

Relevance

GS-III | Environment, Pollution & Public Health

- Demonstrates PM2.5-driven chronic pollution as a slow-onset public-health emergency.

- Highlights gaps in urban environmental governance, enforcement, and real-time risk communication.

Practice Question

- “Air pollution in Indian cities represents a slow emergency rather than a sudden disaster.” Analyse with reference to the Kolkata experience. (250 Words)

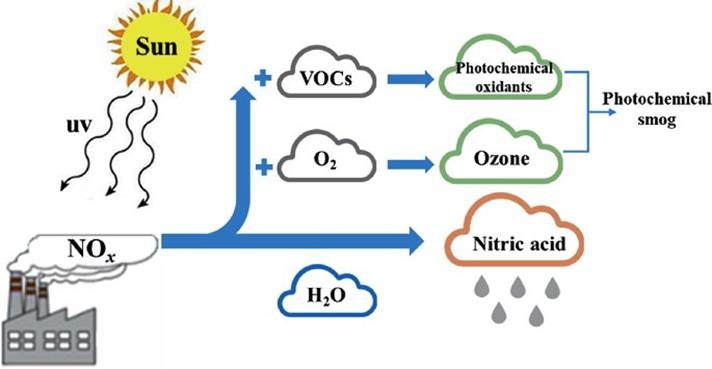

Basics — What is Smog & PM2.5?

- Smog = smoke + fog → mixture of particulate matter + pollutants trapped under winter inversion conditions.

- PM2.5 = fine particles ≤2.5 microns; enter lungs & bloodstream → causes cardio-respiratory disease, stroke, cancers.

- WHO recommended mean PM2.5 level: 5 μg/m³ annually.

- India’s National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS): 40 μg/m³ annually (much higher tolerance than WHO).

Kolkata’s winter PM2.5 levels frequently exceed even India’s relaxed threshold.

Facts & Data from the Editorial

- Real-time monitors (e.g., Victoria Memorial) repeatedly recorded AQI in “very poor” range in December.

- IQAir’s 2024 annual report:

- Kolkata’s PM2.5 mean ≈ 46 µg/m³ — ~9× WHO guideline and close to India’s limit.

- Urban exposure thresholds breached repeatedly — but treated as routine, not emergency.

- Sources of spikes highlighted:

- Vehicular emissions, diesel-run buses/trucks, construction dust, roadwork, open waste burning, industrial emissions, winter inversion trapping pollutants.

- Political response remains performative — sprinklers, bans, campaigns — without structural mitigation.

Why It Matters — Nature of the “Slow Emergency” ?

- Unlike sudden disasters, air pollution harms slowly and invisibly:

- chronic lung disease

- cardiovascular stress

- reduced productivity & life expectancy

- Health crisis becomes socially normalised, delaying accountability.

Governance & Policy Dimensions

- Under-recognition of air pollution as a public-health crisis.

- Weak enforcement of emission norms & transport policy.

- Lack of transparent real-time risk communication.

- Infrastructure bias (flyovers, roadbuilding) over clean-mobility investments.

- Fragmented institutional responsibility — municipal vs. state vs. central agencies.

Key critique: Pollution persists because it is politically invisible and not electorally salient.

Urban Risk Drivers — Kolkata Context

- Old diesel vehicle fleet & mixed-traffic congestion

- Rapid construction + poor dust control

- Informal burning practices

- Port activity & freight corridors

- Limited public-transport electrification

- Meteorological inversion during winter

Health & Economic Impacts

- Long-term PM2.5 exposure linked to:

- ↑ asthma, COPD, stroke, ischemic heart disease

- ↓ worker productivity & cognitive performance

- Studies estimate air pollution costs 2–3% of India’s GDP equivalent (health + lost output).

Kolkata’s “routine smog” therefore implies hidden public-health expenditure & welfare losses.

Comparative Insight

- Delhi receives policy & media spotlight; Kolkata represents India’s second-tier pollution crisis where harm is equally real but poorly discussed.

- The article argues for parity in attention, monitoring, and accountability.

Policy Priorities — Way Forward

- Clean Transport Transition

- phase-out old diesel vehicles; electrify buses & taxis

- strengthen public transport + last-mile connectivity

- Construction & Road-Dust Controls

- strict site-covering, mechanised sweeping, debris regulation

- Real-time Risk Communication

- heat-wave–style health advisories for high-AQI days

- Emission Inventory & Source Apportionment

- science-based targeting of top contributors

- Urban Planning Reforms

- low-emission zones, congestion pricing, walkable corridors

- Health-system readiness

- respiratory clinics, surveillance of pollution-linked morbidity

Conclusion

Kolkata’s winter smog illustrates a “slow emergency” — a case where chronic pollution crosses scientific risk thresholds but remains politically invisible. The crisis stems from transport-construction-inversion dynamics, weak institutional prioritisation, and normalisation of health risk. Effective response requires data-led urban governance, transport decarbonisation, social risk communication, and sustained regulatory enforcement — not symbolic measures.