Content

- 2nd India–Arab Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, 2026

- Is India prepared for the end of globalisation?

2nd India–Arab Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, 2026

Overview

- Ministers and delegates of the Arab League are meeting in New Delhi on January 30–31, 2026, marking a significant diplomatic outreach amid global and regional instability.

Why in news ?

- The second India–Arab Foreign Ministers’ Meeting is being held in Delhi at a time of escalating West Asian conflicts, shifts in global power balance, and heightened strategic relevance of the Arab region for India.

Relevance

- GS 1 (Geography – Resources & Location):

West Asia–North Africa region as a strategic energy, trade-route, and diaspora geography influencing India’s external relations. - GS 2 (International Relations):

India–Arab League institutional diplomacy, strategic partnerships, energy security, counter-terrorism cooperation, and engagement amid West Asian instability.

Practice Question

- In the backdrop of instability in West Asia and a changing global order, examine the strategic significance of the Arab League for India’s energy security, connectivity, and regional diplomacy. (250 words)

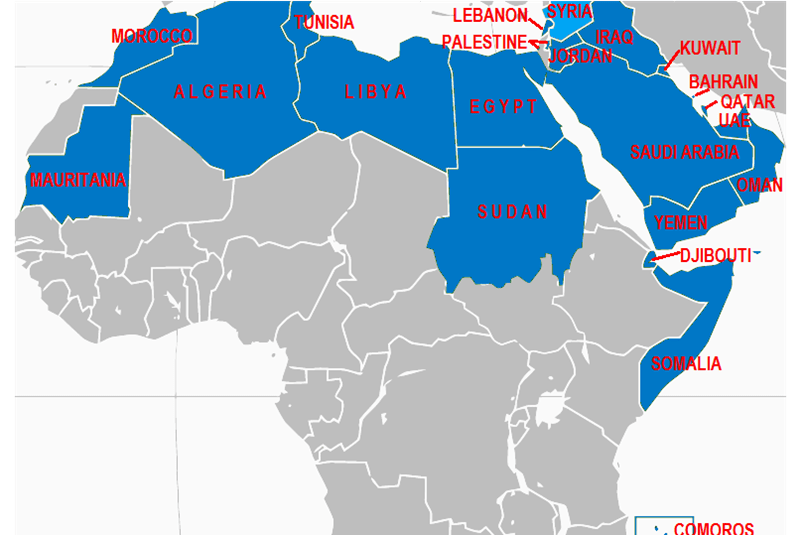

Arab League members (22 countries)

- Arab League consists of 22 member states spanning West Asia and North Africa, formed to promote political, economic, and cultural coordination among Arab countries.

West Asia (Middle East)

- Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Palestine

North Africa

- Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, Sudan, Somalia, Djibouti, Comoros

HQ

- Egypt (Cairo) hosts the headquarters of the Arab League.

- Palestine is a full member.

- Comoros is the only island nation in the Arab League.

Regional and global context

Changing global order

- The contemporary global order is under strain due to unilateral actions by major powers, including the United States under Donald Trump, weakening the rules-based international system and state sovereignty norms.

West Asian security situation

- Persistent tensions involving Iran, fragile ceasefires in Syria and Gaza, and uncertainty over long-term peace underscore the volatility shaping diplomatic calculations of Arab states and external partners like India.

- Emerging fault lines between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, particularly over Yemen and regional influence, raise risks of competing security alignments.

India and the Arab League: background

Institutional evolution

- The Arab League, founded in 1945, today comprises 22 West Asian and North African states, with India formalising engagement through a 2002 MoU enabling structured political dialogue.

- The Arab–India Cooperation Forum was established in 2008, followed by designation of India’s Ambassador to Egypt as Permanent Representative to the Arab League in 2010.

Pillars of India–Arab League engagement

Political and strategic convergence

- India has expanded strategic partnerships with key Arab states since 2008, reflecting convergence on regional stability, counter-terrorism, and long-term development visions.

- Shared strategic outlooks between India’s Viksit Bharat 2047 and Arab national visions such as Saudi Vision 2030 reinforce long-term political alignment.

Trade, investment, and connectivity

- Bilateral trade between India and Arab League countries exceeds USD 240 billion, with the UAE alone crossing USD 115 billion, highlighting deep economic interdependence.

- Major investment commitments include USD 75 billion from the UAE, USD 100 billion from Saudi Arabia, and USD 10 billion from Qatar, largely targeting infrastructure and logistics.

- The India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor enhances strategic connectivity through the Red Sea and Suez routes, critical for India’s external trade flows.

Energy security

- The Arab region supplies about 60% of India’s crude oil, 70% of natural gas, and over 50% of fertiliser imports, making it indispensable for India’s energy and food security.

- Long-term LNG agreements, including a USD 78 billion deal with Qatar for 7.5 million tonnes annually over 20 years, significantly strengthen India’s energy security framework.

Digital and financial cooperation

- Financial technology cooperation has expanded through RuPay card deployment, UPI acceptance across multiple Arab countries, and operationalisation of rupee–dirham settlement mechanisms.

- Acceptance of the Indian rupee at Dubai airports since 2023 reflects growing confidence in India’s digital public infrastructure and currency settlement systems.

Defence and security cooperation

- Defence partnerships with Oman, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Qatar cover joint exercises, maritime security, and defence manufacturing collaboration.

- India’s access to Oman’s Duqm port enhances Indian Navy operational reach and maritime domain awareness in the western Indian Ocean.

- Arab League countries have consistently supported India’s stance against cross-border terrorism, condemning major terror attacks and backing India in multilateral forums.

Strategic significance for India

- The Arab League region is central to India’s energy security, diaspora interests, trade routes, and maritime security, making sustained engagement a strategic imperative.

- India’s growing defence exports, including platforms like Tejas, BrahMos, and Akash, open new dimensions of strategic-industrial cooperation with Arab states.

Way forward outlook

- The 2026 meeting offers an opportunity to deepen political trust, manage emerging regional fault lines, and expand cooperation in cyber, space, drones, and advanced manufacturing.

- Strengthening institutional dialogue with the Arab League positions India as a reliable partner in an increasingly fragmented and uncertain global order.

Value Addition

1st India–Arab Foreign Ministers’ Meeting

- The first India–Arab Foreign Ministers’ Meeting was held in New Delhi in 2018, marking the first collective ministerial-level engagement between India and the Arab League.

- It institutionalised regular political dialogue between India and the 22-member Arab League beyond bilateral country-level interactions.

Is India prepared for the end of globalisation?

Why is it in news?

- In January 2026, U.S. President Donald Trump openly linked tariffs and bilateral pressure to India’s oil import decisions, signalling transactional diplomacy and erosion of the rules-based global trade order.

Relevance

- GS 2 (Governance & Global Order):

Erosion of rules-based international order, decline of multilateralism, and assertion of national sovereignty. - GS 3 (Economy & Development):

Return of mercantilism, industrial policy, supply-chain fragmentation, state capacity, and limits of export-led growth.

Practice Question

- “Globalisation as a political system is giving way to mercantilism.” Explain the implications of this shift for developing countries like India. (150 words)

Context: end of the globalisation era

Globalisation as a political system

- Globalisation was not merely free trade expansion but a political framework governing markets, state behaviour, and multilateral institutions, anchored in liberalism, cooperation, and rule-based international engagement.

- This system relied on assumptions like open markets, free capital mobility, enforceable contracts, and negotiated management of shared global resources, which are now increasingly violated by major powers.

Shift towards mercantilism

- The emerging order treats trade as an instrument of state power, where trade surpluses signal strength and deficits weakness, replacing cooperation with coercive bilateralism and protectionist industrial policies.

Background: evolution of the global economic order

Pre-liberal globalisation

- Early globalisation was built on force and asymmetry, with industrialised nations accumulating wealth through domestic resource extraction and colonial exploitation, producing unequal and non-reciprocal trade structures.

Post–World War II order

- After mid-20th century decolonisation and war devastation, multilateral institutions emerged to manage sovereignty, conflict, and cooperation under a normative framework, even when power was exercised unilaterally.

- The legitimacy of this order depended on restraint and multilateral justification, often framed around democracy, stability, or humanitarianism, rather than explicit national self-interest.

Why the system is breaking down ?

Economic consequences of deep integration

- Deep global integration caused returns to capital to outpace wage growth, intensifying inequality, deindustrialisation in some regions, and over-concentration of manufacturing in others.

- Rising migration pressures and job losses in advanced economies created fertile ground for populist, inward-looking politics, hostile to free trade and multilateral cooperation.

China’s rise as a structural disruptor

- China integrated into global markets while retaining strong state control over capital, labour, and information, benefiting from openness without fully adhering to multilateral liberal norms.

- Persistent Chinese trade surpluses and excess industrial capacity constrained industrialisation prospects of developing economies, including India, altering geopolitical and economic power balances.

Collapse of multilateral cooperation

- Global cooperation is increasingly viewed as a strategic cost, with countries prioritising sovereignty, industrial policy, and domestic political gains over shared global solutions.

- International aid has become conditional on donor national interests, while multilateral institutions struggle to coordinate collective action on climate change and illicit financial flows.

India’s position in the emerging order

Structural contradictions

- India is simultaneously too large to ignore and not large enough to shape rules, limiting its ability to influence a mercantilist global order dominated by major economic powers.

- Over the past decade, India has failed to fully convert its demographic advantage into productive capacity, weakening its leverage in a competitive global economy.

Domestic political economy constraints

- Economic growth has not been matched by broad-based public investment in health and education, resulting in a sharply stratified social structure and weak social mobility.

- Low state capacity and uneven social cohesion reduce India’s ability to compete in a world where economic power increasingly depends on internal resilience and coordination.

Areas of potential Indian strength

- India retains credible potential in digital public infrastructure, renewable energy, services exports, and democratic decentralisation, offering selective pathways to relevance in a fragmented global economy.

- However, realising these advantages requires sustained institutional reform, skill development, and redistribution of growth benefits, rather than reliance on market forces alone.

Way forward: preparedness for a post-globalisation world

- In a mercantilist global order, state capability becomes decisive; weak administrative capacity risks long-term irrelevance regardless of market size or diplomatic rhetoric.

- India needs a renewed social contract focused on shared growth, public investment, and social cohesion to sustain economic competitiveness and political legitimacy.

Core takeaway

- The end of liberal globalisation shifts the burden of success from global cooperation to domestic capability, making state capacity, social cohesion, and equitable growth the decisive determinants of India’s global relevance.

Data points to use in answer writing

- Global trade growth has lagged global GDP growth since 2019, reversing the long-standing globalisation pattern where trade expanded faster than output.

Source: WTO, World Trade Statistical Review. - Geoeconomic fragmentation could reduce global GDP by 2–7% in the medium term due to trade barriers, sanctions, and supply-chain bifurcation.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook. - China accounts for nearly 30% of global manufacturing output, creating excess capacity and crowding out late-industrialising economies.

Source: World Bank; UNIDO Industrial Statistics. - Since 2018, G20 countries have introduced thousands of trade-restrictive measures, signalling structural protectionism rather than temporary shocks.

Source: Global Trade Alert; WTO monitoring reports. - India’s exports-to-GDP ratio remains below 25%, far lower than East Asian manufacturing economies, limiting leverage in a fragmented global trade order.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators. - Manufacturing employs less than 18% of India’s workforce, constraining large-scale job absorption as global value chains fragment.

Source: ILO; Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS). - India’s public expenditure on health and education combined remains below 5% of GDP, weakening long-term productivity and state capacity.

Source: Economic Survey of India; World Bank. - Over 65% of India’s population is of working age, but insufficient job creation risks turning demographic dividend into demographic stress.

Source: UN Population Division; Economic Survey of India. - Services contribute over 50% of India’s total exports, providing partial resilience as manufacturing-led globalisation weakens.

Source: RBI; WTO trade profiles. - Capital remains globally mobile while labour mobility is increasingly restricted, intensifying inequality and political backlash against globalisation.

Source: IMF; World Bank migration and capital flow studies.