Content

- Uttarakhand opens Nanda Devi, 82 other peaks

- Turtle Trails

- SC questions WhatsApp, Meta on personal data

- SC has not upheld death penalty in 3 years

- Solid Fuel Ducted Ramjet (SFDR) technology

- AMR Dipstick Test

- Preventable Cancers in India

- Sundarbans Tourism & Climate Loss

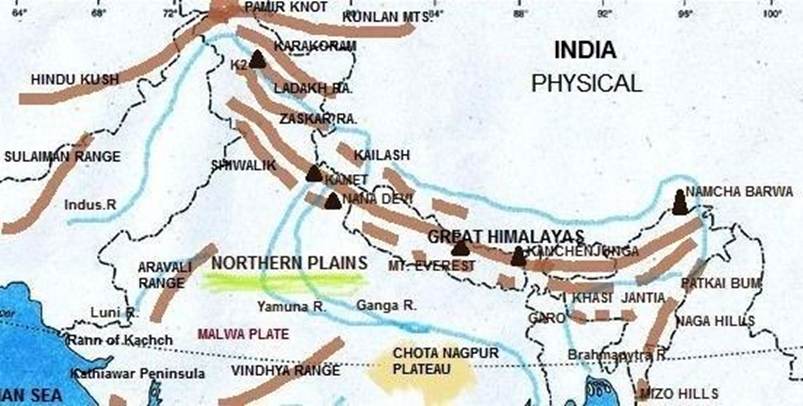

Uttarakhand opens Nanda Devi, 82 other Himalayan peaks for mountaineering

Why in news ?

- Uttarakhand government opened 83 Himalayan peaks (5,700–7,756 m) for mountaineering to promote adventure tourism, expand high-value tourism segments, generate livelihoods, and attract domestic and foreign climbers.

- Iconic peaks like Mount Kamet (7,756 m), Nanda Devi East, Chaukhamba, Trishul, Shivling, Neelkanth included, signalling policy shift toward regulated access to technically challenging high-altitude mountains.

- State waived peak, camping, and environmental fees, and launched a fully digital permission system, reducing entry barriers, improving transparency, and positioning Uttarakhand as a competitive mountaineering destination.

Relevance

- GS1 (Geography): Himalayas, mountain ecology, disasters

- GS2 (Polity/Governance): Environmental regulation, Centre–State roles

- GS3 (Economy/Environment): Sustainable tourism, climate vulnerability

Basics and background

- Adventure tourism involves risk, physical exertion, and natural terrains; includes mountaineering, trekking, rafting, skiing; recognised globally as a fast-growing, high-spending, niche tourism segment.

- Indian Himalayas stretch ~2,500 km across northern India; Uttarakhand’s Garhwal–Kumaon Himalayas host major glaciers, steep relief, and technically demanding peaks attractive to elite climbers.

- Earlier, many peaks remained restricted due to ecological fragility, border proximity, and complex permits, limiting India’s share in global mountaineering compared to more open regimes like Nepal.

Constitutional and legal dimensions

- Tourism is a State subject, but forests and wildlife fall in Concurrent List, requiring coordination between Union and State governments while permitting mountaineering in ecologically sensitive landscapes.

- Activities near protected areas must comply with Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 and Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, ensuring expeditions do not degrade notified ecosystems or wildlife habitats.

- Article 48A and Article 51A(g) impose duties on State and citizens to protect environment, requiring mountaineering policies to integrate conservation safeguards and sustainable use principles.

Governance and administrative aspects

- Shifting financial burden from climbers to government reduces bureaucratic friction, potentially increasing participation, but demands strong regulatory oversight to prevent misuse and ensure environmental compliance.

- The digital mountaineering permission portal improves transparency, real-time tracking, and data availability, enabling better regulation, safety monitoring, and evidence-based policy adjustments.

- Effective implementation requires coordination among Tourism, Forest, Disaster Management authorities, ITBP, and district administrations, especially for rescue operations and environmental monitoring.

Economic dimension

- Adventure tourists spend significantly higher per capita, supporting guides, porters, transporters, equipment rentals, and homestays, creating strong local economic multiplier effects in remote mountain districts.

- Tourism contributes roughly 7–8% of Uttarakhand’s GSDP (estimates), and diversification into mountaineering reduces overdependence on seasonal pilgrimage tourism like Char Dham.

- Opening premium peaks can position Uttarakhand as a high-value, low-volume destination, aligning with sustainable tourism models prioritising quality revenue over mass footfall.

Social and ethical dimension

- Mountaineering promotion can empower local youth with skills, certifications, and employment, reducing distress migration from hill districts and strengthening local mountain economies.

- Ethical concerns include ensuring fair wages, insurance, and safety protections for porters and guides who face disproportionate risks during high-altitude expeditions.

- Some Himalayan peaks hold cultural and spiritual significance, requiring sensitive tourism models that respect local beliefs and traditional relationships with sacred landscapes.

Environmental and disaster dimension

- Himalayas are geologically young, tectonically active mountains, highly prone to landslides, earthquakes, avalanches, and flash floods, making large-scale mountaineering inherently risky.

- Expedition-related waste, campsite pressure, and human disturbance can degrade fragile alpine ecosystems with slow natural regeneration rates and low carrying capacity.

- Past disasters like 2013 Kedarnath floods and 2021 Rishi Ganga flood highlight cumulative risks from climate change, glacial instability, and unplanned human activity.

Data and evidence

- India hosts ~9,500+ glaciers, many concentrated in Uttarakhand, making it hydrologically crucial but also highly vulnerable to climate-induced glacial retreat and hazards.

- Global adventure tourism market exceeds $300 billion, growing around 15–20% annually, indicating strong demand for regulated, high-quality mountain tourism destinations.

- High-altitude ecosystems exhibit low resilience and slow recovery, meaning even small-scale disturbances can have long-lasting ecological impacts.

Challenges and criticisms

- Weak enforcement of waste-return rules and Leave No Trace principles risks accumulation of non-biodegradable waste in pristine high-altitude zones.

- Limited high-altitude rescue infrastructure, weather forecasting, and trauma care reduce safety margins for climbers and local support staff.

- Fee waivers may reduce dedicated conservation funds unless government ensures compensatory environmental financing mechanisms.

- Risk of overtourism and route crowding if promotion outpaces regulation and carrying-capacity assessments.

Way forward

- Conduct scientific carrying-capacity studies for each peak and cap annual expeditions based on ecological and safety thresholds.

- Implement strict waste buy-back policies, eco-certification, and environmental bonds refundable upon compliance with green norms.

- Provide mandatory insurance, training, and safety standards for guides and porters, institutionalising mountain labour welfare.

- Strengthen mountain rescue systems, early-warning networks, and climate monitoring, integrating technology and local knowledge.

- Promote community-based eco-tourism models ensuring revenue sharing, local stewardship, and alignment with SDGs 8, 12, 13, and 15.

Turtle Trails

Why in news ?

- Union Budget announced ‘turtle trails’ along nesting coasts of Odisha, Karnataka, Kerala, triggering concerns among conservationists about tourism pressure on ecologically sensitive marine turtle nesting habitats.

- Focus areas include Gahirmatha, Rushikulya, Devi river mouths in Odisha, globally known for Olive Ridley mass nesting (arribada) events involving hundreds of thousands of turtles.

- Conservationists warn poorly regulated tourism could disturb nesting females, hatchlings, and beach ecology, undermining decades of protection efforts and community-based conservation successes.

Relevance

- GS1 (Geography): Himalayas, mountain ecology, disasters

- GS3 (Economy/Environment): Sustainable tourism, climate vulnerability

Basics and background

- Olive Ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) are small marine turtles famous for arribada, where thousands of females synchronously nest on specific beaches over short periods.

- Odisha hosts one of the world’s largest arribada sites, making India globally significant for Olive Ridley conservation and marine biodiversity protection.

- Turtles exhibit natal homing, returning to the same beaches to nest, making disturbance at key sites capable of disrupting long-established reproductive cycles.

Constitutional and legal dimensions

- Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 (Schedule I) gives Olive Ridley turtles highest legal protection, prohibiting disturbance, hunting, or habitat damage at nesting sites.

- Coastal areas fall under CRZ (Coastal Regulation Zone) Notification, restricting construction and tourism infrastructure near ecologically sensitive coastal stretches.

- Article 48A and 51A(g) mandate environmental protection, requiring tourism projects to align with ecological sustainability and precautionary principles.

Governance and administrative aspects

- Turtle conservation involves MoEFCC, State Forest Departments, Coast Guard, local communities, requiring coordinated regulation of tourism, fishing, and coastal development.

- Budget announcements without detailed carrying-capacity studies or management frameworks raise concerns about implementation clarity and ecological safeguards.

- Effective governance needs clear guidelines on visitor limits, timing restrictions, and lighting controls near nesting beaches.

Economic dimension

- Eco-tourism around turtles can generate local livelihoods for guides, homestays, and conservation workers, especially in coastal rural areas with limited income sources.

- However, unregulated tourism risks short-term gains but long-term ecological losses, ultimately undermining sustainable tourism potential and biodiversity-based economies.

- Global wildlife tourism shows that species decline directly reduces tourism value, linking conservation with long-term economic returns.

Social and ethical dimension

- Local fishing communities often act as frontline turtle protectors, and tourism must not marginalise their traditional livelihoods or knowledge systems.

- Ethical wildlife tourism requires non-intrusive viewing, strict codes of conduct, and awareness, avoiding stress to animals during sensitive nesting periods.

- Over-commercialisation risks turning conservation into spectacle, diluting intrinsic ecological and cultural value of nesting sites.

Environmental dimension

- Turtles are vital for marine ecosystem balance, helping maintain healthy seagrass beds and controlling jellyfish populations, supporting broader ocean productivity.

- Artificial lighting, beach furniture, and human presence can disorient hatchlings, leading them away from sea and increasing mortality.

- Coastal ecosystems already face stress from erosion, pollution, and climate change-driven sea-level rise, compounding threats to nesting habitats.

Data and evidence

- Odisha records lakhs of Olive Ridley nesters during arribada seasons in peak years, making it among the largest global aggregations.

- IUCN lists Olive Ridley as Vulnerable, indicating high risk without sustained conservation interventions.

- Marine turtle survival rates are naturally low, with only a fraction of hatchlings reaching adulthood, increasing importance of undisturbed nesting.

Challenges and criticisms

- Absence of clear definition of ‘turtle trails’ creates ambiguity about scale, infrastructure, and tourism intensity planned at nesting beaches.

- Risk of tourism coinciding with peak nesting season, when disturbance causes maximum ecological damage.

- Weak enforcement capacity in coastal zones can allow illegal construction, noise, and lighting violations.

- Conservationists fear policy signals may prioritise tourism optics over science-based conservation.

Way forward

- Develop science-based eco-tourism protocols with strict visitor caps, seasonal restrictions, and no-construction buffer zones near nesting beaches.

- Ensure community-led conservation tourism, giving locals economic stakes in protecting turtles and regulating tourist behaviour.

- Mandatory environmental impact assessments and carrying-capacity studies before operationalising turtle tourism circuits.

- Promote dark-sky beaches, regulated viewing distances, and trained naturalist guides to minimise disturbance.

- Align initiatives with CBD commitments, SDG 14 (Life Below Water), and precautionary conservation principles.

SC questions WhatsApp, Meta on personal data

Why in news ?

- Supreme Court (2026) questioned WhatsApp–Meta on sharing and commercial use of user data, warning against violating Article 21 privacy rights of millions of Indian “silent consumers.”

- Case relates to challenge against CCI penalty of ₹213.14 crore (2023) imposed for WhatsApp’s 2021 privacy policy update enabling greater data sharing with Meta.

- Court highlighted that data carries economic value, not merely privacy concerns, and sought comparison of India’s law with EU’s stricter digital regulations.

Relevance

- GS2 (Polity): Right to privacy, DPDP Act

- GS2 (Governance): Digital regulation, institutional oversight

Basics and background

- Personal data includes identifiers, location, online behaviour, and metadata; such data fuels targeted advertising, AI training, and platform revenue models in the global digital economy.

- WhatsApp has 500+ million users in India, its largest market globally, making Indian citizens’ data a major economic asset for global tech firms.

- Scholar Shoshana Zuboff terms this model “surveillance capitalism,” where user behaviour is continuously tracked and monetised for predictive advertising.

Constitutional and legal dimensions

- K.S. Puttaswamy (2017) declared privacy a fundamental right under Article 21, including informational self-determination and limits on non-consensual data use.

- DPDP Act, 2023 mandates consent, purpose limitation, and data fiduciary duties, with penalties up to ₹250 crore per breach for non-compliance.

- However, DPDP focuses on privacy harms, not explicitly on economic exploitation or value extraction from aggregated data.

Governance and regulatory aspects

- India’s digital regulation split among MeitY (data protection), CCI (competition), RBI (financial data), TRAI (telecom), creating fragmented oversight over Big Tech platforms.

- CCI found WhatsApp’s policy violated Section 4 of Competition Act (abuse of dominance) by forcing data-sharing conditions on users.

- Supreme Court scrutiny indicates shift toward converged regulation linking privacy, competition, and consumer protection.

Economic dimension

- Global digital advertising market exceeds $600 billion (2024 estimates), with Meta and Google controlling a dominant share using behavioural data analytics.

- Meta’s revenue is ~97% ad-driven, showing direct linkage between personal data profiling and corporate profitability.

- Data-driven network effects create entry barriers, reinforcing Big Tech dominance and raising antitrust concerns.

Social and ethical dimension

- India has ~850 million internet users, but digital literacy remains uneven; many users cannot interpret complex privacy policies or consent architectures.

- Solicitor General noted citizens are “not only consumers but products,” reflecting commodification of user data without direct user compensation.

- Raises ethical issues of informational asymmetry, consent manipulation, and exploitation of vulnerable users.

Technological dimension

- End-to-end encryption protects message content, but not metadata like contacts, timestamps, device data, or behavioural signals used for profiling.

- Studies show metadata can reveal social networks and preferences, often sufficient for targeted advertising without reading messages.

- Cross-platform integration allows Meta to combine Facebook–Instagram–WhatsApp data ecosystems for richer user profiling.

Global comparison

- EU GDPR allows fines up to 4% of global turnover, leading to multi-billion-euro penalties on Big Tech for data violations.

- EU Digital Services Act (DSA) regulates algorithmic targeting and systemic platform risks, going beyond narrow privacy to platform accountability.

- India’s DPDP framework is less stringent on platform power and data value issues.

Data and evidence

- India contributes one of the largest global data pools due to scale of digital public infrastructure and smartphone penetration.

- Surveys show over 90% users accept privacy policies without reading, weakening the legal fiction of informed consent.

- Data brokerage industry globally valued at $250+ billion, built on personal data trade.

Challenges and criticisms

- Consent fatigue makes repeated permissions meaningless, reducing genuine autonomy.

- DPDP lacks explicit provisions on data valuation, revenue-sharing, or algorithmic accountability.

- Enforcement capacity of the Data Protection Board still evolving.

- Balancing innovation and regulation remains a policy tension.

Way forward

- Introduce granular, multilingual, simplified consent dashboards for real informed choice.

- Develop framework on data value, benefit-sharing, and algorithmic transparency.

- Strengthen coordination between MeitY, CCI, and sectoral regulators.

- Build capacity and independence of Data Protection Board.

- Align gradually with global best practices while preserving India’s digital innovation ecosystem.

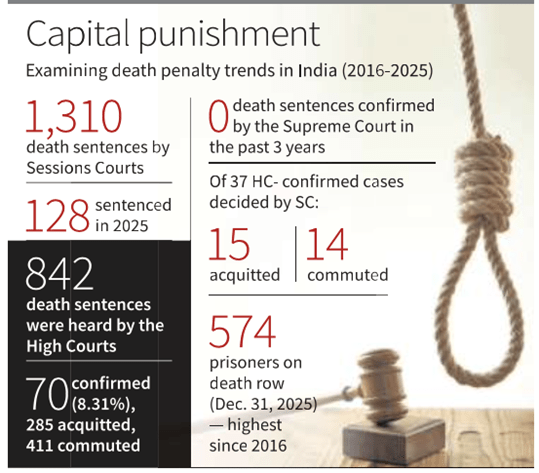

SC has not upheld death penalty in 3 years: report

Why in news ?

- A NALSA–NALSAR Square Circle Clinic (2025) report shows the Supreme Court has not confirmed any death sentence in the last three years, indicating rising judicial caution toward capital punishment.

- 10 death-row acquittals by the Supreme Court in 2025, the highest in a decade, highlight serious concerns about trial accuracy and sentencing standards.

- Data reveal a sharp disconnect between Sessions Courts and appellate courts, raising questions about fairness, evidence appreciation, and sentencing procedures in capital cases.

Relevance

- GS2 (Polity): Judiciary, Article 21, criminal justice

- GS2 (Governance): Due process, legal aid

Basics and background

- Capital punishment in India is legally valid but restricted to the “rarest of rare” doctrine evolved in Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980).

- Death penalty may be awarded for crimes like terrorism, certain aggravated murders, and rape-murder of minors under IPC/BNS and special laws.

- India retains death penalty but uses it sparingly compared to many retentionist countries, with long appellate and mercy review layers.

Constitutional and legal dimensions

- Article 21 permits deprivation of life only by just, fair, and reasonable procedure, forming the constitutional basis for strict scrutiny in death cases.

- Machhi Singh (1983) refined “rarest of rare” by balancing crime and criminal test, requiring consideration of mitigating circumstances.

- Manoj v. State of MP (2022) mandated psychological evaluation and mitigation investigation before awarding death penalty.

- Vasanta Sampat Dupare (2015) elevated fair sentencing hearing to a due process requirement.

Data and evidence

- 1,310 death sentences imposed by Sessions Courts between 2016–2025, indicating continued trial-level reliance on capital punishment.

- Of 842 High Court decisions, only 70 confirmed (8.31%), while 411 commuted and 285 resulted in acquittals, showing high appellate correction rates.

- Supreme Court decided 37 confirmed-HC cases: 15 acquittals, 14 commutations, zero confirmations in last three years.

- 574 prisoners on death row (2025)—550 men, 24 women—with average 5+ years on death row, some nearing a decade.

Governance and judicial process dimension

- High reversal rates indicate systemic weaknesses in investigation, evidence appreciation, and legal aid quality at trial stage.

- Nearly 95% of 2025 death sentences violated SC sentencing guidelines, lacking mitigation studies or psychological reports.

- Sentencing hearings often held within days of conviction, undermining individualised sentencing and defence preparedness.

Social and ethical dimension

- Prolonged death row incarceration creates “death row phenomenon”—mental trauma recognised in jurisprudence as rights concern.

- Disproportionate impact on economically weaker and legally underrepresented accused, raising equality and fairness concerns.

- Ethical debate persists between retributive justice vs reformative justice approaches.

International and comparative dimension

- 140+ countries globally are abolitionist in law or practice (Amnesty data), indicating global shift away from capital punishment.

- International human rights bodies increasingly view death penalty as incompatible with evolving standards of dignity and human rights.

- India remains a retentionist but low-execution country, with very few actual executions in recent decades.

Challenges and criticisms

- Arbitrary application despite “rarest of rare” doctrine leads to sentencing inconsistency explaining high appellate reversals.

- Weak mitigation investigation and poor legal aid reduce fair trial guarantees.

- Delays in appeals and mercy petitions prolong uncertainty and psychological suffering.

- Lack of empirical evidence that death penalty has greater deterrent effect than life imprisonment.

Way forward

- Institutionalise mitigation investigation units and trained sentencing specialists for capital cases.

- Ensure mandatory compliance with Manoj guidelines before confirming death sentences.

- Strengthen legal aid and forensic standards at trial level.

- Consider Law Commission’s earlier recommendations favouring progressive abolition except for terrorism-related offences.

- Move toward life imprisonment without remission as proportionate alternative in heinous crimes.

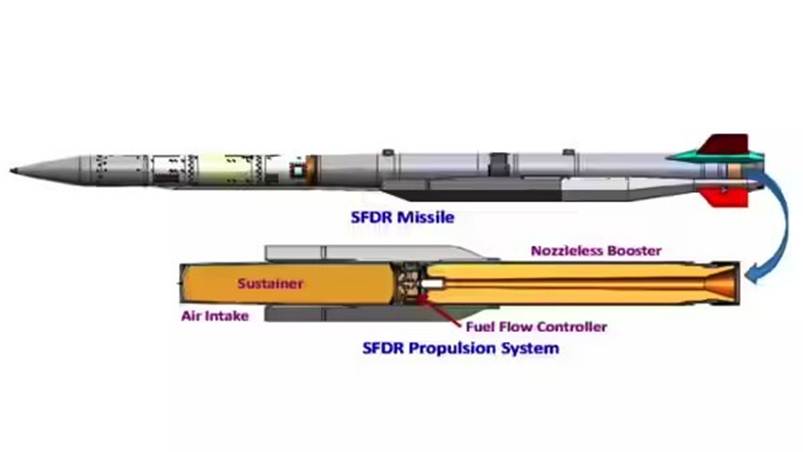

Solid Fuel Ducted Ramjet (SFDR) technology

Why in news ?

- DRDO successfully demonstrated Solid Fuel Ducted Ramjet (SFDR) technology from ITR Chandipur, Odisha, marking a major milestone in India’s advanced missile propulsion and air-combat capability development.

- With SFDR success, India joins a small group of nations possessing this technology, strengthening indigenous capacity for next-generation long-range air-to-air missiles and strategic deterrence.

- Defence Minister termed the test a major boost to Aatmanirbhar Bharat in defence, highlighting growing public–private partnership in high-end missile technologies.

Relevance

- GS3 (Science & Tech): Missile propulsion systems

- GS3 (Security): Defence preparedness, deterrence

Basics and background

- Solid Fuel Ducted Ramjet (SFDR) is an advanced air-breathing propulsion system using solid fuel with ramjet combustion, enabling sustained supersonic speeds and higher missile range than conventional rockets.

- Unlike ballistic propulsion, SFDR uses atmospheric oxygen for combustion, improving fuel efficiency, range, and speed during cruise phase of missile flight.

- SFDR is particularly suited for beyond-visual-range (BVR) air-to-air missiles, enhancing aerial dominance and interception capability against agile enemy aircraft.

Strategic and security dimension

- SFDR-powered missiles allow longer engagement ranges, higher no-escape zones, and sustained high speeds, giving Indian fighters tactical superiority in contested airspaces.

- Strengthens India’s deterrence posture amid regional security competition with China and Pakistan, both investing heavily in advanced missile and air-combat technologies.

- Supports Indian Air Force need for long-range precision engagement, especially in high-altitude or maritime theatres.

Technological dimension

- SFDR integrates ramjet propulsion, nozzle-less boosters, and flame stabilisation systems, demanding high precision in materials, aerodynamics, and combustion control.

- Demonstrates India’s maturity in complex propulsion engineering, an area historically dominated by few advanced defence powers.

- Builds on DRDO’s earlier successes in BrahMos, Astra, Akash, and ballistic missile programmes.

Governance and institutional dimension

- Developed by DRDO with Indian industry partners, reflecting growing defence R&D ecosystem and private-sector participation in strategic technologies.

- Aligns with Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) and indigenisation push, reducing reliance on imported missile systems.

- Supports long-term goal of self-reliance in critical defence technologies.

Economic and industrial dimension

- Indigenous missile technologies reduce high-cost imports and save foreign exchange in defence procurement.

- Boosts domestic defence manufacturing ecosystem under Make in India and defence corridors.

- Potential future defence exports if integrated into operational missile systems.

Global and geopolitical dimension

- Only a few countries like USA, Russia, and some European powers possess operational ramjet/ducted ramjet missile technologies.

- Entry into this group enhances India’s technological credibility and strategic signalling.

- Supports India’s image as a major defence technology developer, not just importer.

Challenges and limitations

- Translating technology demonstration into reliable, deployable missile systems requires extensive user trials and integration with fighter platforms.

- High R&D and testing costs demand sustained funding and long-term policy support.

- Advanced propulsion systems require robust quality control and supply chains.

Way forward

- Accelerate integration of SFDR into Astra Mk-III or future BVR missile programmes for operational deployment.

- Expand collaboration between DRDO, startups, and private industry in propulsion and materials research.

- Invest in testing infrastructure and simulation capabilities to shorten development cycles.

- Link missile R&D with broader theatre command and airpower modernisation strategy.

AMR Dipstick Test

Why in news ?

- Scientists at THSTI Faridabad developed a low-cost dipstick assay to detect antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes in sewage, enabling rapid population-level surveillance in a major public health threat area.

- Study published in Nature Communications (Dec 2025) validated the test across 381 sewage sites in six Indian States, confirming sewage as a major AMR reservoir and transmission pathway.

- The assay costs only ₹400–550 per test, versus ₹9,000+ for shotgun sequencing, making large-scale AMR monitoring feasible for resource-constrained public health systems.

Relevance

- GS2 (Health): AMR policy, public health

- GS3 (Science & Tech): Biotechnology innovation

- GS3 (Environment): One Health, wastewater surveillance

Basics and background

- Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms to survive drugs, making infections harder to treat and increasing morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs globally.

- AMR is driven by antibiotic misuse in humans, livestock, and agriculture, plus pharmaceutical effluents and poor wastewater treatment infrastructure, especially in densely populated developing countries.

- Sewage surveillance captures community-level signals from households, hospitals, farms, and industries, offering early-warning insights into antibiotic use and resistance trends.

Scientific and technological dimension

- The dipstick works like a rapid diagnostic test, detecting amplified resistance genes from sewage DNA using PCR-based amplification and visible colour-band readouts.

- Each dipstick detects 16 resistance genes and provides results within two hours, enabling time-efficient, field-friendly surveillance without advanced laboratory infrastructure.

- The platform is upgradeable within three days if new resistance genes emerge globally, ensuring adaptability to evolving microbial threats.

Public health and governance dimension

- India is recognised as a global AMR hotspot by WHO, with high infectious disease burden and widespread antibiotic access without prescriptions.

- AMR threatens procedures like surgeries, chemotherapy, and organ transplants, where effective antibiotics are critical for infection prevention.

- Low-cost surveillance supports India’s National Action Plan on AMR (NAP-AMR) goals on monitoring and containment.

Economic dimension

- AMR could cause 10 million deaths annually by 2050 globally and reduce global GDP by 2–3.5%, according to international estimates.

- Affordable surveillance reduces long-term healthcare costs by enabling targeted interventions and rational antibiotic stewardship.

- Low-cost diagnostics are vital for LMICs, where high-end genomic surveillance is financially unsustainable.

Social and ethical dimension

- Sewage surveillance is considered ethically acceptable since it monitors communities anonymously without targeting individuals, avoiding privacy and consent concerns.

- Helps protect vulnerable populations who suffer disproportionately from drug-resistant infections due to limited healthcare access.

- Encourages a One Health approach, integrating human, animal, and environmental health.

Data and evidence

- Researchers analysed sewage from 381 locations across Assam, Haryana, Jharkhand, UP, Uttarakhand, and West Bengal, confirming widespread antibiotic residues and resistance genes.

- India has some of the highest antibiotic consumption rates globally, increasing selection pressure for resistant microbes.

- Only a fraction of wastewater in India undergoes effective treatment, facilitating AMR spread.

Limitations and cautions

- Detection of a gene signals possibility of resistance, not presence of a live pathogenic organism; genes alone do not cause disease.

- AMR expression varies by gene combinations and ecological context, requiring cautious interpretation.

- Dipsticks complement but do not replace culture-based and genomic surveillance.

Way forward

- Integrate dipstick surveillance into routine urban wastewater monitoring under public health and Jal Shakti frameworks.

- Link results to antibiotic stewardship programmes and regulation of pharmaceutical effluents.

- Expand AMR labs and genomic surveillance for confirmatory analysis.

- Strengthen wastewater treatment infrastructure under AMR containment strategy.

- Promote global data sharing aligned with WHO Global AMR Surveillance System (GLASS).

Preventable Cancers in India

Why in news ?

- A WHO–IARC linked study estimates ~40% of cancers in India are preventable, highlighting large scope for primary prevention through lifestyle change, vaccination, pollution control, and infection management.

- Study analysed 30 preventable cancers using Indian exposure data on tobacco, alcohol, obesity, infections, diet, and pollution, quantifying attributable fractions for evidence-based cancer control policies.

Relevance

- GS2 (Health): NCD policy, prevention strategy

- GS1 (Society): Lifestyle diseases

- GS3 (Environment): Pollution–health nexus C

Basics and background

- Cancer involves uncontrolled cell growth driven by genetic mutations; risk arises from interaction of lifestyle, environmental exposures, infections, and ageing, making many cancers theoretically preventable through risk reduction.

- Primary prevention targets risk-factor reduction before disease onset, unlike secondary prevention which relies on screening and early detection after disease processes have begun.

Key findings and data

- 37% of new cancer cases in 2022 (~14 lakh cases) were attributable to known preventable risk factors, showing significant avoidable burden within India’s overall cancer incidence.

- Men (50.6%) show higher preventable burden than women (30.3%), reflecting higher tobacco and alcohol consumption patterns among males in India.

- Tobacco alone accounts for 13.4% of cancers, making it the single largest preventable contributor to India’s cancer burden.

- Infections contribute 13.4%, including HPV, hepatitis B/C, and H. pylori, indicating strong role of vaccination and sanitation in cancer prevention.

- Alcohol contributes 6.4%, obesity 5.7%, air pollution 3.9%, showing rising lifestyle and environmental cancer risks alongside traditional factors.

Public health and governance dimension

- India’s cancer burden rising due to epidemiological transition, ageing population, and urban lifestyles, increasing pressure on already resource-constrained oncology infrastructure.

- Prevention aligns with National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, CVD and Stroke (NPCDCS) focusing on screening, awareness, and lifestyle modification.

- Population-level interventions offer higher cost-effectiveness compared to tertiary cancer treatment, which is expensive and infrastructure-intensive.

Social and behavioural dimension

- High-risk behaviours like smoking, smokeless tobacco, unhealthy diets, and sedentary lifestyles are shaped by socio-economic and cultural factors, requiring behavioural-change communication.

- Lower awareness and late diagnosis among poorer groups worsen outcomes, making prevention and early education crucial for equity in cancer control.

Environmental dimension

- Air pollution contributes nearly 4% of cancers, especially lung cancer, linking environmental regulation directly with non-communicable disease control.

- Industrial emissions, vehicular pollution, and biomass burning increase carcinogenic particulate exposure in Indian cities.

Global and comparative perspective

- WHO estimates 30–50% of global cancers are preventable, placing India within global pattern but with higher tobacco and infection-related burden than many developed countries.

- Countries with strong tobacco control and HPV vaccination show significant cancer incidence decline, demonstrating policy effectiveness.

Challenges and gaps

- Weak enforcement of tobacco and alcohol regulations reduces impact of prevention policies.

- Limited HPV and Hepatitis B vaccination coverage constrains infection-related cancer prevention.

- Urban pollution control remains inconsistent despite regulatory frameworks.

- Behavioural change is slow due to addiction and social norms.

Way forward

- Strengthen tobacco taxation, plain packaging, and cessation services to reduce largest risk factor.

- Expand HPV and Hepatitis B vaccination under Universal Immunisation Programme.

- Integrate cancer prevention into Ayushman Bharat–Health and Wellness Centres for grassroots awareness.

- Enforce air-quality standards and promote healthy urban planning.

- Invest in mass awareness campaigns on diet, exercise, and alcohol risks.

Sundarbans Tourism & Climate Loss

Why in news ?

- Debate triggered after Union Environment Minister said Sundarbans tourism is under-exploited, comparing ~9–9.5 lakh annual visitors with ~19 lakh in Ranthambore, raising questions on tourism as climate-adaptation strategy.

- Experts caution that Sundarbans is ecologically fragile, disaster-prone, and densely populated, making scale and model of tourism more critical than raw tourist numbers.

- Context links tourism with climate-induced loss and damage (L&D) and livelihood diversification in one of India’s most climate-vulnerable regions.

Relevance

- GS1 (Geography): Mangroves, coastal vulnerability

- GS2 (Governance): Climate adaptation, disaster policy

- GS3 (Environment): Climate change, biodiversity

Basics and background

- Sundarbans is the world’s largest contiguous mangrove forest (~19,000 sq km across India–Bangladesh) and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, known for biodiversity and Royal Bengal Tiger habitat.

- Indian Sundarbans cover ~4,000 sq km in West Bengal, with over 4.5 million residents dependent on agriculture, fishing, and forest resources.

- Region is low-lying, tidally influenced, and cyclone-prone, making it a frontline zone for sea-level rise and climate extremes.

Climate vulnerability and loss–damage context

- Sundarbans frequently face cyclones, floods, and tidal surges, whose intensity and frequency are rising with climate change in the Bay of Bengal.

- Study across 48 inhabited islands shows agriculture most climate-affected (impact score 4.27/5) and fishery moderately affected (2.52/5).

- Nearly three-fifths of surveyed families reported migration due to disaster-linked livelihood stress, showing climate-induced displacement pressures.

Non-economic loss and damage (NELD)

- NELD includes psychological trauma, cultural erosion, social disruption, and educational discontinuity, often invisible in GDP-based damage assessments.

- Among 75 students (12–16 years) across 10 islands, most experienced ~4 cyclones, with ~60 showing persistent trauma and disaster anxiety.

- Reports show 40 land productivity losses, 25 house damages, 30 school disruptions, indicating deep social impacts beyond economic loss.

Tourism potential: opportunities

- Carefully designed eco-tourism can diversify livelihoods, reducing dependence on climate-sensitive agriculture and fisheries.

- Community-based tourism can generate income for boat operators, guides, homestays, handicrafts, and local services, spreading climate-risk.

- Mangrove and wildlife tourism can incentivise conservation-linked livelihoods, aligning ecology and economy.

Ecological and governance risks

- Sundarbans’ carrying capacity is unassessed, making large-scale tourism scientifically risky for fragile mangrove and delta ecosystems.

- Mangroves act as natural coastal buffers, and ecosystem disturbance can weaken storm protection functions.

- Illegal tourism already violates CRZ norms and NGT orders, reflecting weak regulatory enforcement.

Comparative perspective

- Comparing Sundarbans with Ranthambore is ecologically flawed; Sundarbans is riverine, dispersed, and sighting-based tourism is inherently uncertain.

- Ranthambore supports safari tourism on firm terrain, whereas Sundarbans relies on boat-based, low-density access, limiting scale.

- Tourism models must reflect ecosystem type, hazard exposure, and settlement density.

Institutional and funding dimension

- Sundarbans hold over 42% of India’s mangrove cover, yet West Bengal reportedly receives relatively lower central mangrove-conservation funding.

- Expansion as a major tiger reserve indicates conservation success but also requires balancing tourism with habitat protection.

- Climate adaptation finance and conservation funding remain critical.

Challenges and criticisms

- Risk of over-commercialisation in a fragile delta could damage biodiversity and increase disaster exposure.

- Tourism income may be seasonal and unevenly distributed, not a complete substitute for primary livelihoods.

- Infrastructure expansion can increase ecological footprint and disaster vulnerability.

Way forward

- Conduct scientific carrying-capacity and vulnerability assessments before scaling tourism.

- Promote low-impact, community-based eco-tourism, not mass tourism.

- Strict enforcement of CRZ norms, NGT orders, and mangrove protection laws.

- Integrate tourism with climate adaptation planning and disaster-resilient infrastructure.

- Channel climate finance for livelihood diversification, education, and mental health support.