Why in news ?

- Uttarakhand government opened 83 Himalayan peaks (5,700–7,756 m) for mountaineering to promote adventure tourism, expand high-value tourism segments, generate livelihoods, and attract domestic and foreign climbers.

- Iconic peaks like Mount Kamet (7,756 m), Nanda Devi East, Chaukhamba, Trishul, Shivling, Neelkanth included, signalling policy shift toward regulated access to technically challenging high-altitude mountains.

- State waived peak, camping, and environmental fees, and launched a fully digital permission system, reducing entry barriers, improving transparency, and positioning Uttarakhand as a competitive mountaineering destination.

Relevance

- GS1 (Geography): Himalayas, mountain ecology, disasters

- GS2 (Polity/Governance): Environmental regulation, Centre–State roles

- GS3 (Economy/Environment): Sustainable tourism, climate vulnerability

Basics and background

- Adventure tourism involves risk, physical exertion, and natural terrains; includes mountaineering, trekking, rafting, skiing; recognised globally as a fast-growing, high-spending, niche tourism segment.

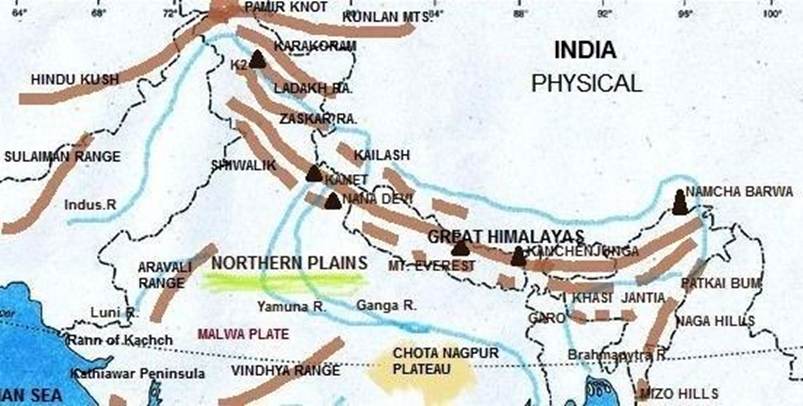

- Indian Himalayas stretch ~2,500 km across northern India; Uttarakhand’s Garhwal–Kumaon Himalayas host major glaciers, steep relief, and technically demanding peaks attractive to elite climbers.

- Earlier, many peaks remained restricted due to ecological fragility, border proximity, and complex permits, limiting India’s share in global mountaineering compared to more open regimes like Nepal.

Constitutional and legal dimensions

- Tourism is a State subject, but forests and wildlife fall in Concurrent List, requiring coordination between Union and State governments while permitting mountaineering in ecologically sensitive landscapes.

- Activities near protected areas must comply with Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 and Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, ensuring expeditions do not degrade notified ecosystems or wildlife habitats.

- Article 48A and Article 51A(g) impose duties on State and citizens to protect environment, requiring mountaineering policies to integrate conservation safeguards and sustainable use principles.

Governance and administrative aspects

- Shifting financial burden from climbers to government reduces bureaucratic friction, potentially increasing participation, but demands strong regulatory oversight to prevent misuse and ensure environmental compliance.

- The digital mountaineering permission portal improves transparency, real-time tracking, and data availability, enabling better regulation, safety monitoring, and evidence-based policy adjustments.

- Effective implementation requires coordination among Tourism, Forest, Disaster Management authorities, ITBP, and district administrations, especially for rescue operations and environmental monitoring.

Economic dimension

- Adventure tourists spend significantly higher per capita, supporting guides, porters, transporters, equipment rentals, and homestays, creating strong local economic multiplier effects in remote mountain districts.

- Tourism contributes roughly 7–8% of Uttarakhand’s GSDP (estimates), and diversification into mountaineering reduces overdependence on seasonal pilgrimage tourism like Char Dham.

- Opening premium peaks can position Uttarakhand as a high-value, low-volume destination, aligning with sustainable tourism models prioritising quality revenue over mass footfall.

Social and ethical dimension

- Mountaineering promotion can empower local youth with skills, certifications, and employment, reducing distress migration from hill districts and strengthening local mountain economies.

- Ethical concerns include ensuring fair wages, insurance, and safety protections for porters and guides who face disproportionate risks during high-altitude expeditions.

- Some Himalayan peaks hold cultural and spiritual significance, requiring sensitive tourism models that respect local beliefs and traditional relationships with sacred landscapes.

Environmental and disaster dimension

- Himalayas are geologically young, tectonically active mountains, highly prone to landslides, earthquakes, avalanches, and flash floods, making large-scale mountaineering inherently risky.

- Expedition-related waste, campsite pressure, and human disturbance can degrade fragile alpine ecosystems with slow natural regeneration rates and low carrying capacity.

- Past disasters like 2013 Kedarnath floods and 2021 Rishi Ganga flood highlight cumulative risks from climate change, glacial instability, and unplanned human activity.

Data and evidence

- India hosts ~9,500+ glaciers, many concentrated in Uttarakhand, making it hydrologically crucial but also highly vulnerable to climate-induced glacial retreat and hazards.

- Global adventure tourism market exceeds $300 billion, growing around 15–20% annually, indicating strong demand for regulated, high-quality mountain tourism destinations.

- High-altitude ecosystems exhibit low resilience and slow recovery, meaning even small-scale disturbances can have long-lasting ecological impacts.

Challenges and criticisms

- Weak enforcement of waste-return rules and Leave No Trace principles risks accumulation of non-biodegradable waste in pristine high-altitude zones.

- Limited high-altitude rescue infrastructure, weather forecasting, and trauma care reduce safety margins for climbers and local support staff.

- Fee waivers may reduce dedicated conservation funds unless government ensures compensatory environmental financing mechanisms.

- Risk of overtourism and route crowding if promotion outpaces regulation and carrying-capacity assessments.

Way forward

- Conduct scientific carrying-capacity studies for each peak and cap annual expeditions based on ecological and safety thresholds.

- Implement strict waste buy-back policies, eco-certification, and environmental bonds refundable upon compliance with green norms.

- Provide mandatory insurance, training, and safety standards for guides and porters, institutionalising mountain labour welfare.

- Strengthen mountain rescue systems, early-warning networks, and climate monitoring, integrating technology and local knowledge.

- Promote community-based eco-tourism models ensuring revenue sharing, local stewardship, and alignment with SDGs 8, 12, 13, and 15.