Content

- Can the ICJ ruling force rich nations to pay for historical emissions?

- How not to identify an illegal immigrant

- Why the world needs better green technologies

- Malaria’s new frontlines: vaccines, innovation, and the Indian endgame

- Mystery of African Mahogany G20 sapling solved

- Language & division of states

Can the ICJ ruling force rich nations to pay for historical emissions?

Core of the ICJ Ruling

- Advisory nature: The ruling is not legally binding, but offers a legal interpretation of existing international obligations under climate law.

- Key reaffirmations:

- Countries are legally obligated to reduce GHG emissions.

- Developed nations must support vulnerable states facing disproportionate climate impacts.

- Reiterates the 1.5°C target from the Paris Agreement as a climate safeguard.

Relevance : GS 3(Environment and Ecology)

Legal & Scientific Challenges

- Causality problem:

- Attribution of specific climate damages to specific countries’ emissions remains scientifically difficult.

- Most extreme weather events are exacerbated, not uniquely created, by climate change, making legal claims tenuous.

- Proof thresholds:

- Courts require clear evidence that a country’s inaction led to measurable harm.

- As warming remains around 1–1.5°C, anthropogenic signals are not always dominant in many weather events.

Geopolitical and Enforcement Constraints

- Sovereignty prevails:

- Nations like the U.S., China, and India are unlikely to alter energy systems due to a non-binding ruling.

- The ICJ has no enforcement arm; any binding action would require UN Security Council backing, which is highly political.

- Selective compliance:

- U.S. has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement and continues fossil fuel subsidies.

- Western nations historically dodge accountability, while developing nations are overregulated by the same legal frameworks.

Implications for Climate Reparations

- Reparations unrealistic:

- History shows little delivery on promised climate finance or reparations; most are repackaged development aid.

- Ted Nordhaus argues reliance on reparations is a “poor trade-off” that hinders energy access in developing nations

- Loss and Damage Fund:

- Though symbolically important, funding remains limited.

- Both Nordhaus and Grover are sceptical it will yield substantial compensation for vulnerable nations.

Domestic Leverage Potential

- Legal value at home:

- Ruling offers activists and courts in treaty-ratifying countries a legal foundation to challenge their own governments.

- Likely to be used more in domestic courts than in international litigation.

- Vulnerable nations:

- Small Island Developing States (SIDS) may use this to bolster local climate litigation and international diplomatic leverage.

Shift in Global Technological Dynamics

- Tech flow no longer unidirectional:

- China now leads clean tech exports, including to the West; India may follow.

- This undercuts the 1990s assumption of one-way tech transfer from rich to poor countries.

- Modernising frameworks:

- The ICJ ruling operates within the outdated “common but differentiated responsibilities” (CBDR) model.

- There’s a call for a new global climate framework reflecting multi-polar tech development.

Equity vs Pragmatism

- Ecomodernist critique (Nordhaus):

- Efforts to “co-opt Western legal mechanisms” for equity (e.g., Loss and Damage Fund, ICJ rulings) have failed.

- Advocates domestic development-first strategies using all available resources.

- Climate justice perspective (Grover):

- Acknowledges double standards in global legal norms.

- Urges developing nations to act for their own sake, citing examples like Delhi’s air pollution and corporate capture of energy policy.

Future Outlook

- ICJ ruling ≠ Global shift:

- Unlikely to trigger a wave of international litigation, despite some political claims (e.g., U.K. Shadow Energy Secretary).

- Tool, not a solution:

- Best viewed as a strategic instrument for domestic action — not a global accountability game-changer.

- Political reality check:

- Courts alone can’t force decarbonisation; global politics, power asymmetries, and economic interests dominate.

How not to identify an illegal immigrant

Context & Administrative Trigger

- Timeframe: Winter 2024, during Delhi’s cold wave.

- Trigger: Order from Delhi Lt. Governor Vinai Kumar Saxena directing the police to identify “illegal” foreign nationals, especially post-regime change in Bangladesh.

- Result: Surge in detentions of Bengali-speaking residents across urban slums in Delhi.

Relevance : GS 2(Governance , Social Issues)

Operational Pattern of Crackdown

- Primary Targets: Bengali-speaking residents, particularly in jhuggi settlements.

- Indicators Used for Profiling:

- Language spoken (Bangla dialects).

- Anonymous community tips on dialect and origin.

- Clothing (e.g., lungi), and remittance patterns.

- Key Concern: Reliance on linguistic and cultural profiling rather than legal documentation or due process.

Linguistic Bias & Stereotyping

- Systemic Issue: A narrow perception of Indian Bengali identity, dominated by urban Kolkata dialects and pop culture.

- Misconceptions:

- Treating non-Kolkata dialects or rural Bangla as “foreign”.

- Misreading commonly used words like “paani” as non-Indian — despite their historical presence in early Bengali texts like Charyapada (8th century).

- Result: Cultural markers wrongly used as nationality tests.

Legal & Structural Shortcomings

- Neglect of Contextual Realities:

- No consideration of 2015 India-Bangladesh land swap, where residents could opt for Indian citizenship.

- No nuance in assessing mixed-status families or cross-border remittances.

- Example: Indian citizen detained solely for sending money to elderly parents in Bangladesh.

Ethnic & Cultural Profiling

- Cultural identifiers used as suspicion markers:

- Lungi as an alleged “foreign” garment.

- Remittances equated with cross-border illegality.

- Cultural pushback: Protest songs and local resistance narratives question this overreach — “Just because I wear a lungi… doesn’t mean I was born in Bangladesh.”

Class, Caste & Identity Intersections

- Initially impacted: Bengali Muslims.

- Now widened to: Lower-caste Hindu Bengalis.

- Emerging Trend: A complex overlap of ethnicity, caste, class, and dialect defines vulnerability — not legal status.

Public Discourse & Elite Silence

- Noted Absence: Limited response from Bengali public intellectuals in media, literature, or academia.

- Key Questions:

- Is there a class detachment within Bengali society?

- Are elite Bengalis silent due to discomfort with working-class dialects and attire?

Broader Implications

- Xenophobic Normalization: Language and attire increasingly seen as proxies for illegality.

- Institutional Fragility:

- Weak documentation processes.

- Absence of legal aid for suspected individuals.

- Lack of linguistic and cultural training for enforcement agencies.

- Risk: Deepening intra-ethnic, class, and religious fault lines.

Key Takeaways

- Legal due process must override cultural inference in determining immigration status.

- Language, class, and dress cannot serve as lawful indicators of citizenship.

- A balanced approach requires institutional training, community engagement, and safeguards against arbitrary profiling.

Why the world needs better green technologies

Context & Key Question

- Backdrop: Global climate targets and energy independence goals are driving a massive push for renewable energy.

- Core Issue: Are silicon photovoltaics (Si-PV) still the best option, or should we invest in next-gen solar technologies with higher efficiency and lower environmental impact?

Relevance : GS 3(Environment and Ecology)

Silicon Photovoltaics (Si-PV): Overview

- Invented: 1954, Bell Labs (USA).

- Efficiency:

- Lab efficiency: 18–21%.

- Real-world (in-field) efficiency: 15–18%.

- Global Production:

- 80% of supply from China.

- India: Domestic capacity at ~6 GW, expected to rise.

Efficiency vs. Land Constraints

- Efficiency matters: Doubling efficiency → halves land requirement.

- Land crunch:

- Rapid urbanization.

- Environmental concerns limiting greenfield solar expansion.

- Implication: Silicon PV’s lower efficiency makes it less viable in space-constrained or high-demand areas.

Alternative Photovoltaic Technologies

- Gallium Arsenide (GaAs) Thin-Film: Up to 47% efficiency.

- Commercial-readiness: Many next-gen PVs are lab-tested, demonstration-ready, and awaiting commercial deployment.

Energy & Climate Dynamics

- Renewable Energy Installed (India): 4.45 TWh (by end-2024).

- Atmospheric CO₂: Increased from 350 ppm (1990) to ~425 ppm (2025).

- Implication: Renewable expansion isn’t keeping pace with energy demand.

Green Hydrogen: Promise vs. Reality

- Production method: Electrolysis using renewable power.

- Challenges:

- Electrolysis is energy-intensive.

- Storage & transport of hydrogen is difficult (leaky, low-density).

- Energy cascade losses: From Si-PV → electrolysis → storage → reconversion = compounding inefficiencies.

Proposed Alternatives

- Molecular Carriers: Convert H₂ to green ammonia (NH₃) or green methanol (CH₃OH) for transport.

- But reverse conversion still demands high energy.

- Artificial Photosynthesis (APS):

- Directly produce fuels from H₂O, CO₂/N₂, and sunlight.

- Still in lab-stage, but promising for future.

- CO₂ Recycling: Turn CO₂ into useful fuels = climate mitigation + energy solution.

Europe’s Lead: RFNBO

- Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin (RFNBO):

- Fuels made using renewables but not from biomass.

- Includes green hydrogen, methanol, ammonia from sunlight and air.

- Policy push: India urged to follow suit to reduce 85% energy import dependence.

India’s Strategic Needs

- Current import dependence: 85% of energy (oil, coal, gas).

- Geopolitical vulnerability: Global conflicts + price shocks.

- Recommendation: Ramp up R&D spending, foster public-private innovation.

Conclusion & Takeaways

- Green hydrogen & Si-PV are helpful but not enough.

- Efficiency and energy economics need urgent innovation.

- India must diversify energy strategies to:

- Improve energy density.

- Optimize land use.

- Enable cleaner, scalable fuels.

- Proactive R&D investment today is more cost-effective than reactive damage control tomorrow.

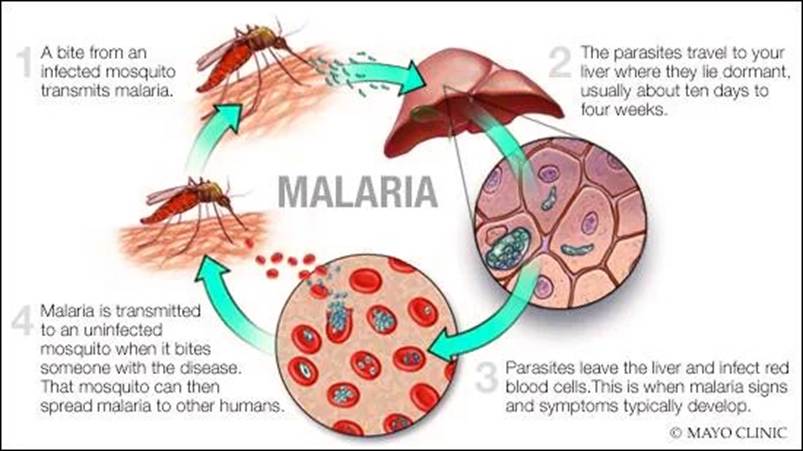

Malaria’s new frontlines: vaccines, innovation, and the Indian endgame

Malaria control in India has entered a decisive phase, powered by vaccine breakthroughs and innovation. Yet, persistent tribal hotspots and policy gaps challenge the 2030 elimination goal.

Relevance : GS 2(Health , Governance)

India’s Progress & Persistent Challenges

Achievements:

- >80% reduction in malaria burden between 2015–2023.

- National ambition: Elimination of malaria by 2030.

Persisting Hotspots:

- Tribal districts still highly affected:

- Lawngtlai (Mizoram): 56+ cases/1000 people.

- Narayanpur (Chhattisgarh): 22+ cases/1000 people.

- Mixed infections: In Jharkhand, 20% of cases involve both P. falciparum & P. vivax.

- Asymptomatic carriers: Silent transmission even in low-incidence zones.

Malaria Parasites in India

- P. falciparum (Africa-dominant): More lethal.

- P. vivax (Asia-dominant): Dormant liver stage → late relapses.

- P. cynomolgi (monkey malaria): Crucial research model for P. vivax, but underutilized in India.

First-Generation Vaccines

1. RTS,S (Mosquirix)

- Approved in 2021.

- Protection: ~55% initially, wanes in 18 months.

- Requires 4 doses.

2. R21/Matrix-M (Oxford–Serum Institute)

- WHO-approved in 2023.

- Up to 77% efficacy in Phase 3.

- Low-cost, fewer doses, room-temperature stable → ideal for India.

Limitations of Current Vaccines

- Target only one life stage (pre-erythrocytic).

- Vulnerable to reinfection and continued transmission.

- Need for multi-stage or whole-parasite strategies.

Next-Gen Vaccine Approaches

A. Whole-Parasite Vaccines

- PfSPZ (Sanaria):

- Uses radiation-weakened sporozoites.

- 96% antibody response, up to 79% protection after 3 doses.

- PfSPZ-LARC2:

- Modified version with potential for single-dose use.

- Targeted use in outbreaks/migrant populations.

B. Blood-Stage Vaccines

- PfRH5:

- Blocks red blood cell invasion.

- Strain-transcending protection.

- Promising Phase 1a/2b trials in UK, Gambia, Burkina Faso.

C. Transmission-Blocking Vaccines (TBVs)

- Pfs230D1 (Mali):

- Blocks fertilization in mosquito gut.

- 78% reduction in transmission (Phase 2).

- India’s TBV candidate – AdFalciVax:

- Combines PfCSP + Pfs230/Pfs48/45.

- Completed preclinical testing in 2025.

- Mice: >90% protection with long immune memory (4+ months).

- Room temp stable (9 months) → ideal for rural India.

- P. vivax TBV (Pvs230D1M):

- First human trial in Thailand: up to 96% transmission reduction.

Immune Boosting & Novel Platforms

Protein-Based Innovations

- Ferritin nanoparticle + CpG adjuvant:

- Cut liver-stage parasite burden by 95% in mice.

- PfCSP–MIP3α fusion:

- Enhances antibody + T-cell response.

- Reduced infection by 88% in mice.

mRNA-Based Platforms

- Pfs25-mRNA (CureVac + NIH):

- Complete transmission block in mice.

- Antibodies lasted 6+ months after 2 doses.

- BNT165e (BioNTech):

- Blood-stage mRNA candidate.

- Trial paused by FDA in 2025.

Parasite Evasion & Immune Engineering

- RIFIN proteins bind to LILRB1 receptors, silencing immune cells.

- Antibody D1D2.v-IgG (India):

- Binds RIFIN 110x stronger than natural receptor.

- Restores immune response in lab tests.

Vector Control Innovations

CRISPR Gene Drives

- Fertility-suppressing drives:

- Eliminated entire Anopheles gambiae colonies in lab within a year.

- FREP1 gene edit:

- Blocks parasite growth inside mosquito.

- Spread to 90% of lab mosquitoes in 10 generations.

Smart Mosquito Designs

- Engineered to die early if infected → self-limiting transmission.

- Prevents ecological disruption by preserving uninfected mosquito populations.

Institutional & Policy Gaps

Key Challenges:

- Lack of:

- Trained doctors,

- Surveillance for resistance, and

- Robust vector control systems.

- India’s P. vivax research underutilised due to:

- Restricted monkey access, outdated priorities.

Steps Ahead:

- ICMR Expression of Interest (2025):

- For industrial partners to co-develop AdFalciVax.

- Critical needs:

- GMP-grade production, immune biomarkers, and efficacy benchmarking vs RTS,S & R21.

Takeaways

| Category | Key Insight |

| Burden | >80% reduction, but pockets like Mizoram & Chhattisgarh remain high |

| Parasites | India fights both P. falciparum & P. vivax (harder to eliminate) |

| Vaccines | RTS,S, R21, PfSPZ, PfRH5, TBVs like AdFalciVax under rapid development |

| Tech | mRNA, nanoparticle, CRISPR gene drives, immune-modulating antibodies |

| Goal | Malaria elimination by 2030 |

| Need | Vaccine innovation + ecosystem of diagnostics, training, and policy support |

Mystery of African Mahogany G20 sapling solved

Background: G20 Plantation at Nehru Park

- Occasion: India’s G20 Presidency (2023).

- Event: Ceremonial plantation of saplings by G20 member countries and invited international organisations.

- Location: Designated plantation area in Nehru Park, New Delhi.

- Objective: Symbolic diplomacy using ecologically significant trees representing each country.

Relevance : GS 3(Environment and Ecology)

The Mystery

- Issue Raised: A citizen-led platform (X, formerly Twitter) flagged that the sapling labelled “African Mahogany” didn’t resemble the actual species.

- Trigger: Viral post with over 28 lakh views, prompting questions on whether species verification had occurred.

- Official Clarification:

- The currently standing sapling is a substitute, not the original African Mahogany gifted by Nigeria.

- The original sapling died after being planted due to non-acclimatisation.

Scientific & Bureaucratic Process

- Plant Quarantine:

- Imported plants underwent a required quarantine at ICAR-NBPGR, New Delhi.

- Pre-plantation Vetting:

- Involved expert species identification to maximize survival in Delhi’s climate.

- Sources Confirmed:

- Substitutes like Jamun (Indian species) were temporarily planted to maintain visual and aesthetic consistency.

Country-wise Sapling Details

- South Korea & South Africa:

- Their original saplings failed to survive post-plantation.

- Embassies confirmed it was within expected parameters.

- South Korea has already replaced its original species.

- Nigeria’s African Mahogany:

- Has now been sourced again and will be planted after the monsoon, as per ideal conditions.

Broader G20 Tree Representation

- A total of 17 tree species were planted by G20 countries and international organisations.

- Symbolism & Environmental Relevance:

- Turkey, Spain, Italy: Olive trees.

- South Korea: Silver tree.

- Egypt, Saudi Arabia: Date Palm.

- Indonesia: Frangipani.

- China: Camphor Laurel.

- African Union: Sausage Tree, Red Frangipani.

Coordination & Logistics

- Nodal Agency: New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC).

- Coordination: Ministry of External Affairs (MEA).

- Challenges Faced:

- Survival in new climate.

- Visual aesthetics of the ceremonial area.

- Ensuring embassy-level approval before using substitutes.

Key Takeaways

- Plant survival in alien climates is a known challenge; substitution is a standard protocol.

- Visual consistency maintained via indigenous look-alike species (like Jamun).

- Embassies remained involved in the replacement process, ensuring diplomatic sensitivity.

- The episode reflects eco-diplomacy, biosecurity procedures, and public accountability.

Language & division of states

Background Context

- Triggering Event: TN Governor R. N. Ravi criticized the linguistic basis of state formation, arguing it led to second-class citizenship for some populations.

- Core Debate: Whether the linguistic reorganisation of states in 1956 was a divisive or unifying force for India.

Relevance : GS 2(Social Issues )

India Before First Reorganisation (1956)

- Dual System of Administration:

- British India: Directly administered provinces.

- Princely States: Indirect rule through native rulers.

- Constitutional Classification (1950):

- Part A: Former British provinces, governed by elected legislatures.

- Part B: Former princely states, governed by Rajpramukhs.

- Part C: Commissioners’ provinces + some princely states.

- Part D: Andaman & Nicobar Islands (governed by the Centre).

- Total States/UTs on 26 January 1950: 28 states + 6 Union Territories.

Linguistic Reorganisation of States (1956)

- Key Trigger: Demands for states based on linguistic and cultural identity surged post-Independence.

- Major Catalyst: Potti Sriramulu’s death (1952) during a fast for a Telugu-speaking state (Andhra) sparked widespread protests → creation of Andhra State.

- Political Response:

- Fazl Ali Commission (SRC) formed in 1953.

- Submitted report: 30 September 1955.

- Recommended reorganisation of India into 16 states & 3 UTs based on administrative efficiency + linguistic affinity.

Data Highlights: After 1956 Reorganisation

- States created based on dominant languages:

- Andhra Pradesh (Telugu)

- Kerala (Malayalam)

- Karnataka (Kannada)

- Tamil Nadu (Tamil)

- Maharashtra (Marathi)

- Gujarat (Gujrati)

- States that were reorganised or merged:

- Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Bihar, Bombay, Madras, etc.

- Part A, B, C, D classifications abolished.

- New structure: Unified system with elected legislatures and clearer administrative boundaries.

Key Arguments For Linguistic Reorganisation

- Unity Through Identity:

- Linguistic states ensured that diverse language groups felt included, preventing alienation.

- Nehru’s Pragmatic Approach:

- Despite early caution, Nehru eventually supported linguistic states to manage unrest and enhance governance.

- Democratic Accommodation:

- Recognised linguistic identities as part of a plural democratic ethos.

- Successful Model:

- Scholar Ramachandra Guha and others note that linguistic reorganisation helped unify rather than divide India.

Governor R. N. Ravi’s Criticism (2025)

- Core Concern: Linguistic division has made many feel like second-class citizens.

- Quote: “In my own state Tamil Nadu… people live together but once it became a linguistic state, one-third became second-class.”

- Implication: Suggests that linguistic politics led to exclusion, particularly for linguistic minorities in each state.

Counterpoints to Governor’s View

- SRC’s Balanced Approach:

- Rejected rigid linguistic determinism; argued for unity & cultural balance.

- Historical Complexity:

- Bombay and Punjab saw violent protests during their linguistic splits (e.g. Bombay’s bilingual state demand).

- State Unity Beyond Language:

- Example: Maharashtra and Gujarat, despite being split, remained stable politically and economically.

Broader Implications for Indian Federalism

- Language as a Unifying Principle:

- While controversial, it has remained core to India’s identity management.

- Limits of Linguistic Logic:

- Not applied uniformly — e.g., Punjab-Haryana division also involved religious and regional considerations.

- Ongoing Challenges:

- Demands for new states (e.g., Gorkhaland, Vidarbha) still persist.

- Need to address intra-state linguistic minorities’ rights.

Conclusion: A Mixed Legacy

- Reorganisation of 1956 was a pragmatic response to post-Independence challenges.

- Despite criticisms, it largely succeeded in:

- Reducing secessionist tendencies.

- Ensuring regional representation.

- Preserving national unity amidst cultural diversity.

- However, interior exclusions and new grievances require renewed attention within federal policy frameworks.