Content

- Decoding the SC order on regulatory assets

- On call 24/7: a spotlight on gig workers who are running the new economy

- Made in India Vikram Processor and Semicon India 2025

- How dead birds, old maps are helping scientists track biodiversity loss

- Why do women in India face higher cancer incidence but lower mortality than men?

- Odisha’s ‘Dongar’ cultivation in danger

Decoding the SC order on regulatory assets

Basics

- DISCOMs (Distribution Companies):

State-run/private companies responsible for last-mile electricity distribution to consumers. - Annual Revenue Requirement (ARR):

- Total revenue DISCOMs are allowed to recover through tariffs + government subsidies.

- Reflects approved expenditure (power purchase, O&M, interest, depreciation, return on equity).

- Average Cost of Supply (ACS):

- Actual cost incurred by DISCOMs to supply one unit of electricity to consumers.

- Includes cost of buying power, transmission, distribution losses, etc.

- ACS-ARR Gap:

- If ACS > ARR, DISCOM makes a loss per unit supplied.

- Causes financial stress since revenue ≠ cost.

- Regulatory Asset (RA):

- Mechanism to defer recovery of revenue gap.

- SERCs allow DISCOMs to record unrecovered costs as “regulatory assets” instead of immediately increasing tariffs.

- Costs deferred for recovery in future years (with interest).

Relevance:

- GS II (Polity & Governance – Role of Judiciary in enforcing financial discipline)

- GS III (Economy – Infrastructure: Power sector, Distribution reforms, Subsidy management, Tariff rationalisation)

Supreme Court Order (2025)

- Existing regulatory assets to be cleared within 4 years.

- New regulatory assets must be liquidated within 3 years.

- Cap: RA ≤ 3% of a DISCOM’s ARR.

- Transparent recovery roadmaps to be prepared by SERCs.

- Intensive audits for DISCOMs failing to recover assets.

Why ACS-ARR Gap Persists?

- Non-cost reflective tariffs: Populist policies keep tariffs artificially low.

- Delayed subsidies: States delay subsidy transfers for agriculture/BPL households.

- Rising input costs: Sudden hikes in coal/gas prices increase power purchase costs.

- Technical & commercial losses: Theft, billing inefficiencies, high AT&C losses.

Impact of Regulatory Assets

- Short-term benefit: Tariffs don’t rise sharply, consumers shielded temporarily.

- Long-term burden: Deferred costs accumulate → future tariff shocks.

- Carrying cost (interest): Consumers ultimately pay higher than original gap.

- Cash flow stress: DISCOMs can’t pay power generators on time → risk of load shedding.

- Debt trap: DISCOMs borrow to bridge gap → rising liabilities.

- Modernisation impact: Funds locked in unrecovered costs → less investment in smart grids, renewable integration, and consumer services.

Examples

- Punjab (2003-04): First RA created (₹487 crore gap, ₹150 crore deferred).

- Delhi (2024-25):

- BSES Rajdhani: ₹36,057 crore RA.

- BSES Yamuna: ₹22,040 crore RA.

- Tata Power Delhi: ₹8,226 crore gap.

- Tamil Nadu (2021-22): ₹89,375 crore RA → systemic stress.

Consumer Impact

- Example: Delhi DISCOMs need to recover ₹16,580 crore annually within 4 years.

- With 30 billion units consumed annually, tariff hike ≈ ₹5.5/unit if immediate recovery attempted.

- Hence RAs are used, but deferred hikes become steeper over time.

Way Forward

- Tariff Rationalisation:

- Tariffs must reflect actual cost.

- Targeted subsidies for vulnerable consumers (DBT model).

- Timely Subsidy Payments:

- States should release subsidies on time → prevent revenue gap.

- Automatic Cost Pass-through:

- Mechanisms like Fuel & Power Purchase Cost Adjustment (FPPCA) allow quick tariff revision with fuel cost changes.

- Annual True-up Exercises:

- Regular reconciliation of projected vs. actual costs to avoid backlog.

- Financial Discipline:

- SERCs must enforce strict RA caps.

- DISCOMs must cut AT&C losses and improve billing efficiency.

- Grid Modernisation Financing:

- Ring-fence funds for grid upgrades, smart meters, and renewable integration separate from RA recovery.

- Judicial Oversight:

- SC’s intervention acts as a disciplinary push for States, regulators, and DISCOMs.

On call 24/7: a spotlight on gig workers who are running the new economy

Basics

- Gig Economy: A labour market characterised by short-term, contract-based, or freelance work mediated largely through digital platforms.

- Examples: Food delivery (Swiggy, Zomato), cab services (Uber, Ola), e-commerce delivery (Amazon, Flipkart), freelance IT/creative work.

- Scale:

- 7.7 million workers (2020–21) → projected 23.5 million by 2029–30 (NITI Aayog, 2022).

- India’s digital economy projected at $1 trillion in the next five years.

Relevance:

- GS II (Polity & Governance – Welfare schemes, Social security, Labour laws, Rights of workers)

- GS III (Economy – Employment trends, Informal sector, Digital economy, Future of work)

- GS I (Society – Changing urban lifestyles, Consumerism, Inequality)

- Essay/Case Study (Ethics & Society – Human dignity, Invisible labour, Tech-driven inequality)

Opportunities Created

- Job Creation: Provides income opportunities to millions, especially youth, migrants, and semi-skilled workers.

- Flexibility: Workers can choose working hours, multiple platforms, and supplement income.

- Consumer Convenience: Rapid service delivery (cabs, food, groceries) transforming lifestyles.

- Digital Inclusion: Entry point into the formal digital economy for low-skill workers.

- Post-COVID Acceleration: Pandemic pushed adoption of digital platforms and AI-enabled gig work.

Challenges for Workers

- Precarity & Insecurity: No fixed wages, job security, or guaranteed hours.

- Low Wages: Long hours for meagre earnings; often below minimum wage equivalents.

- Algorithmic Control: Workers are monitored, incentivised, and penalised by opaque algorithms.

- Lack of Social Security: No health insurance, pensions, paid leave, or accident coverage by default.

- Psychological Stress: Pressure to meet delivery targets; isolation and lack of worker identity.

- Exploitation of Aspirations: Platforms market “flexibility” but often trap workers in exploitative cycles.

Broader Social Implications

- Consumerism Boom: Instant delivery culture fuels demand but erodes human connection (faceless delivery).

- Urban Culture Shift: Traditional vendor-customer relationships replaced by impersonal transactions.

- Income Disparity: Platform owners earn exponentially compared to gig workers.

- Invisible Labour: Consumers rarely acknowledge or engage with delivery workers’ struggles.

Policy & Legal Dimensions

- Lack of Recognition: Gig workers often not categorised as “employees” under labour law.

- Social Security Code, 2020: First attempt to extend protections (like provident fund, insurance) to gig/platform workers, but implementation remains weak.

- State Responses:

- Rajasthan Gig Workers Welfare Act, 2023 – world’s first legislation creating a welfare fund for gig workers.

- Other states exploring welfare boards and data-sharing obligations for platforms.

- Unionisation & Resistance: Increasing strikes and protests by delivery and cab drivers demanding fair wages and social security.

Literary & Cultural Reflections

- Film – Zwigato (2022): Captures life of food delivery workers – insecurity, pressure, family struggles.

- Books:

- OTP Please (2025) – Voices of gig workers across South Asia, consumerism critique.

- Gig Economy in India Rising (2020) – Gig work as future of jobs, flexible but precarious.

- The Gig Economy in India (2025, Pradip Thomas) – Examines State–entrepreneur–platform dynamics.

- Global works (Gigged 2018, The Gig Economy 2019) – highlight precarity and future of work debates.

Way Forward

- Formalisation with Flexibility: Recognise gig workers as a distinct labour category with rights.

- Social Security Framework: Mandatory health, accident, and pension coverage funded jointly by platforms and governments.

- Algorithmic Transparency: Platforms must disclose rating, payment, and penalty systems.

- Collective Bargaining: Encourage unions and digital worker associations.

- Consumer Awareness: Build empathy and responsibility among users of gig services.

- Long-Term Reform: Integrate gig workers into labour codes, welfare boards, and skilling initiatives.

Made in India Vikram Processor and Semicon India 2025

Basics

- Event: Semicon India 2025 (annual semiconductor conference).

- Highlight: Union IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw presented PM Modi a ‘Made in India’ Vikram 32-bit Processor Launch Vehicle Grade chip.

- Developers:

- Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC), ISRO.

- Semiconductor Laboratory (SCL), Chandigarh.

- Legacy: Upgraded version of VIKRAM1601 (16-bit processor), used in ISRO launch vehicle avionics since 2009.

Relevance:

- GS III (Science & Tech – Indigenisation of technology, Semiconductor industry, ISRO achievements, Atmanirbhar Bharat in high-tech)

- GS II (Governance – Industrial policy, Public–private–academia partnerships)

- GS III (Economy – Strategic industries, Electronics manufacturing, Supply chain resilience)

- Essay/IR (Geopolitics – Semiconductor wars, India as alternative hub vs Taiwan/China/US)

About the Vikram 32-bit Processor

- Category: Launch Vehicle Grade Microprocessor.

- Function: Used in avionics systems of ISRO’s launch vehicles.

- Upgradation: From 16-bit (VIKRAM1601) → to 32-bit (higher processing power, reliability, and efficiency).

- Significance:

- Enhances self-reliance in critical semiconductor technology.

- Reduces dependence on foreign aerospace-grade processors.

- Boosts India’s space missions (efficiency, safety, speed).

Academic & R&D Collaboration

- Memento also included 31 prototype chips developed by academic institutions:

- IIT Jammu, IIT Roorkee, IIT Dhanbad, NIT Durgapur, NIT Calicut, IIT Ropar, etc.

- Reflects strong academia–industry–government collaboration in semiconductor R&D.

India’s Semiconductor Push

- Five Semiconductor Units: Under construction rapidly.

- One pilot line already completed.

- Two more to start production in coming months.

- Policy Framework:

- Stable, investor-friendly semiconductor policies.

- Focus on covering design, fabrication, packaging, and supply chain.

- Pitch to Global Players: India projected as manufacturing hub amidst global supply chain uncertainties.

Strategic Significance

- National Security:

- Semiconductor self-sufficiency reduces vulnerability to supply chain shocks.

- Critical for defence, space, telecom, and AI systems.

- Economic Growth:

- Semiconductor industry projected as foundational for India’s $10 trillion economy target.

- Creates high-tech jobs and skilling opportunities.

- Geopolitics:

- In a world dominated by Taiwan, South Korea, U.S., and China in semiconductors → India positioning itself as an alternative hub.

Challenges

- High Capital Requirement: Semiconductor fabs need billions of dollars in investment.

- Global Competition: Taiwan (TSMC), South Korea (Samsung), U.S. (Intel), and China’s state-led push.

- Supply Chain Dependence: Raw materials, advanced lithography machinery (ASML, Netherlands) still external.

- Technology Catch-up: India is a late entrant compared to decades of global R&D.

How dead birds, old maps are helping scientists track biodiversity loss

Basics

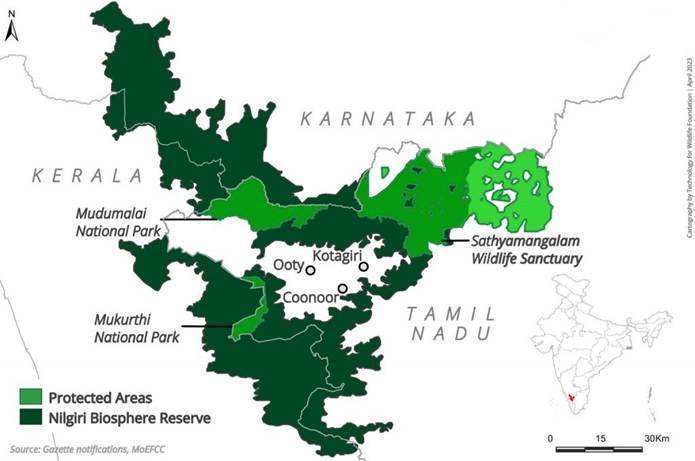

- Nilgiri Mountains: Part of Western Ghats → a global biodiversity hotspot, rich in endemic species (Nilgiri pipit, Nilgiri sholakili, Nilgiri laughingthrush).

- Biodiversity Monitoring Challenge: Current field studies show only a “snapshot”; long-term biodiversity loss requires historical baseline comparisons.

- Role of Museums & Archives: Preserve old specimens, maps, and notes → crucial for studying species decline, habitat change, and climate impacts.

Relevance:

- GS III (Environment – Biodiversity conservation, Habitat loss, Climate change impact, Grassland ecology)

- GS I (Geography – Human–environment interaction, Land-use change, Western Ghats ecosystems)

- GS I (History – Colonial records as scientific resources, Museums as repositories)

- Essay (Heritage & Ecology – Role of archives, science–society linkage in conservation)

The Study (Vijay Ramesh et al., Global Change Biology, 2025)

- Data Sources:

- Bird specimens from British-era natural history museums (late 1800s).

- Old land-use maps (e.g., Captain John Ouchterlony’s 1848 Nilgiri land-cover map).

- Contemporary field surveys across 42 sites.

- Modern satellite imagery.

- Methodology:

- Digitisation of historical museum specimens + maps.

- GIS-based land-use change analysis (1848–2018).

- Bayesian statistical tool (FAMA – field abundance–museum abundance) → estimated species’ relative abundance.

Key Findings

- Grassland Decline:

- 80% reduction → from 993 sq. km (1848) → 201 sq. km (2018).

- Grassland birds most affected: Nilgiri pipit, Malabar lark.

- 90% decline in relative abundance of grassland birds.

- Forest Birds Stability:

- 53% of forest bird species showed stable populations.

- Reason: Grasslands converted into wooded forests (plantations + invasive woody species).

- Indicates habitat “substitution” but not genuine conservation.

- Conservation Blind Spot:

- Grasslands not recognised as critical ecosystems.

- Policies & public perception focus on “forests” and tree planting → inadvertently harm grasslands.

Significance of Museums in Conservation

- Functions:

- Preserve historical records of species distribution & abundance.

- Aid taxonomy & species identification.

- Enable studies on long-term ecological changes (migration, size shifts, community collapse).

- Baseline data for conservation planning.

- Examples:

- Dead birds collected 150 years ago → now key evidence of species decline.

- Old maps digitised → show land-cover shifts invisible in short-term monitoring.

Challenges

- Access Issues:

- Most collections in Western museums (colonial legacy).

- High costs, visa barriers for Indian researchers.

- Institutional Barriers:

- Lack of digitisation in Indian archives.

- Funding constraints & bureaucratic hurdles.

- Ethical Concerns:

- Specimens collected from India but housed abroad → question of ownership & repatriation.

Broader Ecological Insights

- Grassland Neglect: Seen as “wastelands” → converted into plantations, agriculture, or urban land.

- Historical Baselines: Essential to understand true extent of biodiversity loss (short-term data underestimates decline).

- Climate Change Link: Land-use change + temperature rise → shift in ecosystems, pushing species to edge of survival.

Why do women in India face higher cancer incidence but lower mortality than men?

Understanding Cancer Incidence & Mortality

- Incidence: Number of new cancer cases diagnosed in a population during a specific time period.

- Mortality: Number of deaths due to cancer in the same period.

- Crude Incidence Rate (CIR): New cancer cases per 100,000 population.

- Age-Adjusted Incidence Rate (AAIR): Statistical measure adjusted for differences in age distribution across populations (older populations naturally have more cancer cases).

Relevance:

- GS II (Health – Public health, Disease burden, Cancer screening, Gendered healthcare inequality)

- GS I (Society – Gender issues, Women’s health & nutrition, Patriarchy in healthcare access)

- GS III (Science & Tech – Preventive healthcare, Vaccination, Epidemiology)

- Essay/Case Study (Ethics – Healthcare equity, Gender justice, Lifestyle diseases)

Current Trends in India (2015–2019, PBCR Data)

- Incidence:

- Women: 51.1% of cases (≈700,000 cases).

- Men: 48.9%.

- Mortality:

- Men: 55% of cancer deaths.

- Women: 45%.

- Most common cancers:

- Women: Breast, cervical, ovarian.

- Men: Oral, lung, prostate.

- Regional hotspot: Northeast India (Aizawl, Kamrup Urban, Papumpare, East Khasi Hills).

Why Women Face Higher Cancer Incidence

- Biological & Reproductive Factors

- Hormonal exposure (estrogen, progesterone) → breast & ovarian cancer risk.

- Delayed childbirth, fewer pregnancies, reduced breastfeeding.

- Menstrual/reproductive patterns linked to higher hormone exposure.

- Lifestyle & Environmental Changes

- Sedentary lifestyle, obesity, poor diet (processed foods, low fibre).

- Alcohol & tobacco use rising among women.

- Pollutants in air, chemicals in cosmetics, pesticides, processed foods → hormone-related cancers.

- Occupational & Social Risks

- Entry into workforce (exposure to chemicals, night shifts).

- Greater susceptibility to infections (e.g., HPV for cervical cancer).

- Gender inequality → poor nutrition, limited screening access, lower economic parity.

Why Women Have Lower Cancer Mortality

- Nature of Predominant Cancers

- Breast & cervical cancers → relatively higher survival rates if detected early.

- Breast cancer: 5-year survival >90% (early diagnosis, treatment).

- Cervical cancer: Preventable via HPV vaccination, detectable through Pap smears.

- In contrast, men’s cancers (oral, lung, liver) are highly aggressive with poor survival outcomes.

- Awareness & Screening

- Large-scale campaigns for breast & cervical screening.

- HPV vaccination drives (though limited) improving survival chances.

- Women’s reproductive health often a focus in public health interventions.

- Behavioral Factors

- Men have higher tobacco & alcohol use → aggressive cancers + late diagnosis.

- Men less likely to seek preventive healthcare compared to women.

Why Women’s Mortality is Rising Faster Now

- Healthcare Gaps: Late-stage diagnosis, poor rural access to oncology facilities.

- Socioeconomic Barriers: Costs of treatment, patriarchal decision-making limiting healthcare spending on women.

- Misdiagnosis & Delays: Symptoms ignored, stigma around breast/cervical exams.

- Double Burden: Women face biological susceptibility + structural neglect.

- Trend Projection: Over the next 2 decades, female cancer deaths projected to rise faster than men’s (Lancet 2025).

Key Takeaways

- Higher Incidence: Women more exposed to reproductive, hormonal, and lifestyle-linked risk factors.

- Lower Mortality (Currently): Women’s cancers more survivable with early detection, while men’s cancers (oral/lung) have poor outcomes.

- Alarming Trend: Mortality among women is rising quickly due to healthcare inequality, misdiagnosis, and changing lifestyles.

- Policy Priority:

- Expand HPV vaccination & cervical screening.

- Tackle environmental pollutants & unsafe cosmetics.

- Integrate cancer detection in primary health systems.

- Address gender bias in healthcare access & affordability.

Odisha’s ‘Dongar’ cultivation in danger

Dongar Cultivation

- Meaning: Dongar = traditional upland/mountain slope farming system of the Kondh tribes in Odisha.

- Method: Mixed cropping of millets, pulses, oilseeds, tubers → ensures food diversity, nutrition, and ecological balance.

- Parallels: Similar to bewar system in Madhya Pradesh’s Dindori district.

- Tools: No ploughing, only hand tools; fully organic; depends on seed exchange and community labour.

- Significance:

- Climate-resilient system.

- Ensures food sovereignty and cultural identity of Kondh tribes.

- Maintains biodiversity and soil health.

Relevance:

- GS I (Geography – Traditional farming systems, Agro-ecology, Millets, Shifting cultivation parallels)

- GS III (Environment – Sustainable agriculture, Biodiversity conservation, Climate-resilient farming)

- GS I (Society – Tribal livelihoods, Culture, Food security, Nutrition)

Rise of Eucalyptus Monoculture in Rayagada

- Agents: Outsiders linked to paper mills (mainly from southern states).

- Strategy:

- Leasing tribal lands for eucalyptus plantations.

- Providing seedlings, fertilisers, and easy loans.

- Buy-back arrangements ensure assured market.

- Spread: From lowlands → midlands → uplands (dongar areas).

- Economics: Farmers get only ₹1,500–₹3,000 per acre annually when leasing land, much below food/fodder value.

- Attractiveness: Eucalyptus is low-maintenance, grows in 5 years, requires little care compared to millet/pulse farming.

Problems of Eucalyptus Monoculture

- Food Security & Nutrition Loss

- Reduces cultivation of millets, pulses, tubers.

- Forces dependence on PDS rice + tamarind, leading to loss of nutrition.

- Decline in tribal food diversity and seed heritage.

- Ecological Impacts

- Soil Infertility: Eucalyptus depletes nutrients, reduces fertility.

- Water Stress: High water absorption → groundwater depletion.

- Biodiversity Decline: Birds, tubers, and natural foods vanish in eucalyptus areas.

- Monocultures worsen vulnerability to climate change.

- Economic & Social Issues

- Meagre lease incomes compared to livelihood losses.

- Landowners prefer leasing to mills rather than to tribal farmers → tribals lose access to land.

- Tribal youth shifting away from dongar → cultural erosion.

Resistance & Revival Efforts

- Living Farms NGO:

- Active in ~200 villages.

- Working with Talia Kondhs & Kutia Kondhs.

- Promoting awareness drives on climate-resilient dongar farming.

- Reviving seed conservation and organic methods.

- Encouraging rejection of chemicals, revival of labour exchange practices.

- Community Role:

- Women and elders sharing traditional farming knowledge.

- Farmers experimenting with millet revival (ragi, maize) against cotton and eucalyptus.

Broader Context

- Millets in Danger: Despite 2023 being International Year of Millets, upland millet cultivation is collapsing under eucalyptus + BT cotton pressure.

- Climate Change Lens: Studies show monoculture plantations (perennials) more vulnerable to climate change than mixed cropping.

- Policy Vacuum:

- No strict restrictions on plantation companies leasing tribal land.

- Easy credit for eucalyptus vs neglect of millet promotion.

- Weak extension services for traditional crops.

Key Takeaways

- Eucalyptus monoculture = short-term commercial profit but long-term loss of food security, ecology, and tribal identity.

- Dongar = climate-smart, biodiversity-rich, nutrition-sustaining farming system → must be revived.

- Solution Pathways:

- Strengthen millet promotion schemes (link with MSP, PDS).

- Provide institutional credit for dongar farming.

- Legal safeguards against exploitative land leasing.

- Promote seed banks, community-based conservation, and youth involvement.

- Recognise dongar as a model of climate-resilient tribal agroecology.