Content

- India-China: the inability to define a border

- Lost in space? You might need just two stars to find your way

- Building a city of the future

- The foreign capital question

- BTR (Bodoland Territorial Region) GI-tagging initiative

- The Vanishing Practice of Apatanis

India-China: the inability to define a border

Why in News

- The 1993 Border Peace and Tranquillity Agreement (BPTA) between India and China marked a turning point in managing border tensions.

- It remains central to understanding the evolution of India-China border mechanisms, especially after later violations (e.g., Ladakh 2020).

Relevance: GS II (International Relations – Border Disputes, Bilateral Agreements), GS III (Security – LAC Management, Confidence-Building Measures).

Basics

- Background:

- India-China border dispute intensified post-1962 war.

- Rajiv Gandhi’s 1988 Beijing visit revived dialogue after decades of hostility.

- Six rounds of talks (1988–1993) via the Joint Working Group (JWG).

- BPTA (1993):

- Signed during PM P.V. Narasimha Rao’s visit to Beijing.

- First formal document recognizing the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

- Nine-article framework for peaceful border management.

- 1996 Agreement:

- Expanded on 1993 provisions.

- Introduced military confidence-building measures (CBMs) (force limits, arms restrictions, exercise regulations).

Comprehensive Overview

- Diplomatic Breakthrough (1988–1993)

- Revival of bilateral ties: reopening border trade, consulates, defence exchanges.

- BPTA set the principle of peaceful consultations and non-use of force.

- Key Features of BPTA (1993)

- Commitment to resolve boundary issue peacefully.

- Both sides to respect and not overstep the LAC.

- Troop presence limited to “minimal forces,” reductions based on mutual and equal security.

- Agreement to jointly verify disputed LAC segments.

- Aim: Freeze the situation and expand cooperation in other fields.

- Strengthening with 1996 Agreement

- Codified CBMs:

- Force ceilings in sensitive sectors.

- Restrictions on heavy armaments near the LAC.

- Prohibition of large-scale military exercises near LAC or directing them towards the other side.

- Acknowledged that implementation required common LAC understanding → exchange of maps was crucial but failed.

- Codified CBMs:

- Failure of LAC Clarification

- Map exchanges (2000–2002) failed due to maximalist claims.

- By 2005, process abandoned.

- Disputed points: Depsang, Pangong Tso, Demchok, Chumar, etc. → later became flashpoints (e.g., Galwan 2020).

- Strategic Significance

- Shift from outright hostility to a framework of managed competition.

- Agreements reflected parallel economic liberalisation in both nations—peace on the border was prerequisite for growth.

- However, absence of a common LAC definition left the door open for recurring standoffs.

- Lessons & Legacy

- Agreements created a peace management regime, not a resolution of the dispute.

- Worked for two decades (relative peace until 2013–14).

- Violations (especially in 2020) exposed fragility of the framework.

- Reinforces the need for clear demarcation mechanisms, not just CBMs.

Lost in space? You might need just two stars to find your way

Why in News

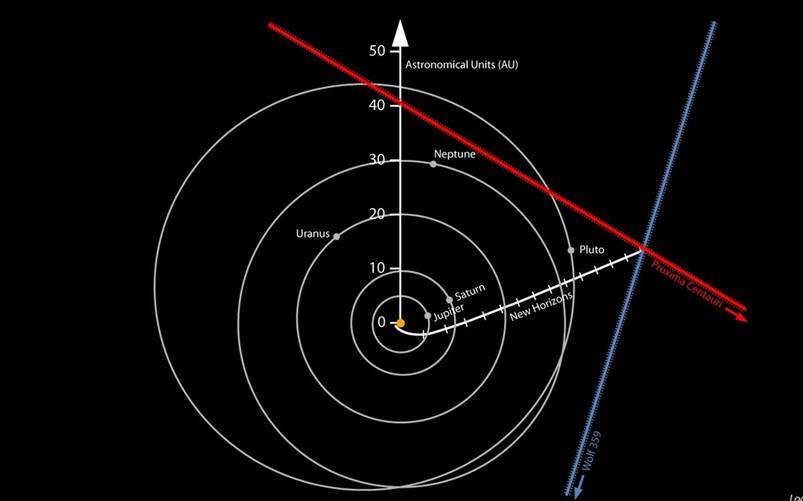

- A June 2024 study (published in The Astronomical Journal) demonstrated that NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft could determine its position in deep space using only two stars (Proxima Centauri and Wolf 359) through stellar parallax.

- This provides a potential low-cost navigation method for future interstellar missions, where Earth-based tracking becomes impractical.

Relevance: GS III (Science & Technology – Space Exploration, Navigation Systems), GS II (International Cooperation – NASA Missions, Global Research).

Basics

- New Horizons Mission:

- Launched: 2006, by NASA.

- Major milestones: Pluto flyby (2015), Kuiper Belt exploration.

- As of 2024: 60+ AU (astronomical units) from Earth, setting a distance record.

- Current Navigation:

- Uses NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN): global radio antennae tracking spacecraft relative to Earth.

- Limitations:

- Earth-centric → delays increase with distance.

- Weakening signal strength → less reliability in deep space.

- Stellar Parallax Method:

- Same principle used historically to measure star distances.

- Observed shift in star positions when viewed from two widely separated vantage points.

- In 2020, New Horizons was 7 billion km from Earth, providing an unprecedented “baseline” for stellar parallax.

Comprehensive Overview

- The Experiment

- Stars used: Proxima Centauri (4.2 light years) and Wolf 359 (7.9 light years).

- Measured parallax:

- Proxima Centauri → 32.4 arcseconds.

- Wolf 359 → 15.7 arcseconds.

- Derived spacecraft distance: 46.89 AU, closely matching DSN estimate of 47.11 AU.

- Tools needed: only a camera, spacecraft computer, and stellar catalogue.

- Significance

- Proof-of-concept: shows navigation possible without Earth’s beacons.

- Cost-effective: no specialized equipment beyond standard payload.

- Scalable: accuracy improves with better cameras/sensors.

- Limitations

- Accuracy insufficient for current navigation of New Horizons.

- Still reliant on DSN at present distances (~60 AU).

- Intended as a demonstration, not operational deployment.

- Future Applications

- Interstellar Missions: critical once signals from Earth become too delayed or weak.

- Self-reliant spacecraft: reduces dependence on ground stations.

- Can integrate with:

- Stellar Astrometric Navigation: uses multiple stars, accounts for relativity.

- Pulsar Navigation: uses neutron stars as “cosmic GPS beacons,” more precise but needs initial positioning input (where stellar parallax can assist).

- Broader Perspective

- Represents a shift from Earth-dependent navigation to autonomous celestial navigation.

- Parallels “explorers at sea using stars as compass,” but scaled to interstellar distances.

- Strengthens capability for long-duration missions (Voyager successors, exoplanet probes).

Building a city of the future

Why in News

- The World Bank report “Prosperous Cities in India” highlights the urgency of building resilient, climate-ready, and inclusive urban infrastructure as India prepares for rapid urbanisation.

- By 2070, India’s urban housing demand will require building twice the existing stock, presenting both risks and opportunities.

- Urban flooding, climate change, and weak planning currently make Indian cities highly vulnerable, requiring systemic reforms.

Relevance: GS I (Urbanisation – Demographic Shifts), GS II (Governance – Urban Planning, Policy Reforms), GS III (Environment – Climate Resilient Infrastructure, Disaster Management).

Basics

- Urbanisation Context:

- India’s urban population is expected to nearly double in the next 25 years.

- By 2070, India’s population will approach 1 billion in urban centres.

- Nearly 70% of infrastructure needed by 2070 is yet to be built.

- Key Risks for Indian Cities:

- Extreme weather (floods, cyclones, heatwaves).

- Rapid housing demand: 140 million new houses required by 2070.

- Inadequate transport & drainage infrastructure.

- Informal housing in hazard-prone areas.

- Opportunity Window:

- Current phase of infrastructure creation allows India to build climate-resilient, inclusive, and sustainable cities.

- Requires large-scale investment, better governance, and citizen participation.

Advanced Overview

Urbanisation as an Opportunity & Challenge

- Demographic Dividend: With millions of young people entering the workforce, cities will be hubs of innovation and job creation.

- Megacity Transition: Several Indian cities are projected to exceed populations larger than many countries, requiring new governance models.

- Risk of Disorderly Growth: Without proactive planning, urbanisation could worsen slum proliferation, congestion, and inequity.

Housing Demand & Climate Vulnerability

- Over 50% of housing stock for 2070 is yet to be built, meaning decisions taken now will determine resilience for decades.

- Current housing patterns:

- Informal, unregulated, often in floodplains or unstable slopes.

- Lacks adequate drainage, ventilation, and disaster preparedness.

- Implication: Without climate-sensitive planning, new housing could lock in high-risk vulnerabilities.

Floods & Infrastructure Weaknesses

- Urban Flooding Trends: Increasingly common in Bengaluru, Chennai, Mumbai.

- Causes:

- Encroachment on wetlands and floodplains.

- Impervious surfaces preventing water absorption.

- Outdated stormwater drainage.

- Data Point: Three-fourths of India’s urban roads are directly exposed to flooding risks.

Integrated Urban Resilience Approach

- Nature-based solutions:

- Restore wetlands, rivers, and urban forests to absorb excess water.

- City-wide drainage with sponge-city models (e.g., China’s urban planning reforms).

- Green-Blue Infrastructure: Treat stormwater not as waste but as a resource.

- Multi-sectoral Planning: Linking housing, transport, waste management, and energy grids under climate-proof frameworks.

Transport and Connectivity

- India’s urban productivity depends heavily on efficient transport systems.

- Flood-disrupted roads cause productivity loss, logistical delays, and economic damage.

- Investments in resilient road networks and public transport are essential to maintain mobility during extreme weather.

Economic & Social Implications

- Cost of Inaction: By 2030, climate-related urban damages could exceed $150 billion annually.

- Equity Concern: Poor and vulnerable populations are most exposed—living in hazard-prone areas with least adaptive capacity.

- Urban Productivity Loss: Flooding and extreme heat reduce labour productivity, increase healthcare costs, and disrupt supply chains.

Governance & Policy Framework

- Institutional Reforms Needed:

- Strengthen municipal finance for infrastructure investment.

- Enhance urban planning capacity with data-driven GIS mapping of risks.

- Foster public–private partnerships for affordable housing and resilient infrastructure.

- Citizen Engagement: Community-level early warning systems, participatory planning, and neighbourhood-scale resilience building.

Strategic Way Forward

- Adopt National Urban Resilience Mission integrating housing, transport, water, and waste management.

- Scaling Nature-based Solutions: Expand green buffers, wetlands restoration, rainwater harvesting.

- Financing Innovation: Climate bonds, municipal bonds, and World Bank-led climate funds.

- Technology Integration: Satellite data for flood risk prediction, AI-based urban modelling.

- Inclusive Growth: Ensure resilience planning does not marginalize urban poor but integrates affordable housing and basic services.

Conclusion

- India’s urbanisation path is at a crossroads: it could either lock in fragile, climate-vulnerable cities or become an opportunity to create resilient, productive, and inclusive urban hubs.

- With more than half of future housing and infrastructure yet to be built, the next 25 years are decisive.

- Investing in climate-smart housing, resilient transport, and nature-based infrastructure will be crucial to sustain urban productivity, reduce risks, and unlock India’s full economic potential.

The foreign capital question

Why in News

- Despite being the world’s fastest-growing major economy (7.4% in FY 2023-24, 7.8% in Apr–Jun 2025 quarter), India’s foreign capital inflows are at a decade-and-a-half low.

- FY 2023-24 saw net FPI inflows of just $2.5 billion, lowest since FY 2018-19, with FDI also stagnating compared to previous years.

- Raises concerns about why India’s growth momentum has not translated into higher foreign investments.

Relevance: GS III (Economy – Foreign Capital, BoP, FDI/FPI), GS II (Policy – Ease of Doing Business, Investment Climate).

Basics

- Foreign Capital Inflows = Investment from abroad into Indian economy. Two key types:

- FDI (Foreign Direct Investment): Long-term, in productive assets.

- FPI (Foreign Portfolio Investment): Short-term, in stocks/bonds.

- Balance of Payments (BoP): Record of all economic transactions.

- Capital Account (inflows like FDI/FPI, external commercial borrowings).

- Current Account (trade deficit + invisibles like remittances).

- India’s BoP history:

- Net capital inflows peaked at $107.9 bn (2007-08).

- Declined to $15.8 bn in FY 2023-24, despite high GDP growth.

Advanced Overview

The Paradox

- Strong GDP growth + low capital inflows = mismatch.

- Normally, higher growth attracts more foreign capital.

- India’s inflows in FY 2023-24 are just 15% of 2007-08 peak levels, despite being the fastest-growing major economy.

Factors Behind Low Inflows

- Shift in FPI preference:

- Earlier FPI went into equities; now focus is on debt, commercial bonds, and alternative assets.

- Risk aversion post-Global Financial Crisis & COVID-19: Preference for stable, safe assets globally.

- Rising domestic savings in India: Less dependence on foreign capital.

- High valuations in Indian equity markets: Discourage foreign investors.

- Policy environment: Public sector-led capex growth crowds out FDI/FPI interest.

- Global monetary tightening: Higher US interest rates pull capital to developed markets.

Balance of Payments Implications

- Merchandise trade deficit widening due to strong domestic demand and high imports.

- Remittances (~$125 bn in 2023-24) and IT/other service exports partly offset trade deficit.

- But low capital inflows strain BoP, limiting RBI’s ability to build forex reserves.

Strategic Concerns

- Dependence on domestic savings makes growth self-reliant, but foreign inflows remain crucial for:

- Infrastructure financing.

- Technology transfer.

- Reducing current account vulnerability.

- FDI stagnation reflects concerns about India’s business environment despite “ease of doing business” claims.

Key Numbers

- 2007-08 peak inflows: $107.9 bn.

- FY 2021-22 inflows: $88.2 bn.

- FY 2022-23 inflows: $53.4 bn.

- FY 2023-24 inflows: $15.8 bn (lowest in 15 years).

- Current Account Deficit (Apr-Jun 2025): $10.2 bn.

Conclusion

- India’s rapid GDP growth has not translated into higher foreign capital inflows, which are now at their lowest in 15 years, creating a growth–capital mismatch.

- Global monetary tightening, high domestic equity valuations, and policy-driven public capex dominance have made India less attractive for FPI/FDI compared to safer or alternative assets.

- While domestic savings and remittances cushion the BoP, sustained low foreign inflows could constrain forex reserves, infrastructure financing, and long-term investment climate.

BTR (Bodoland Territorial Region) GI-tagging initiative

Why in News

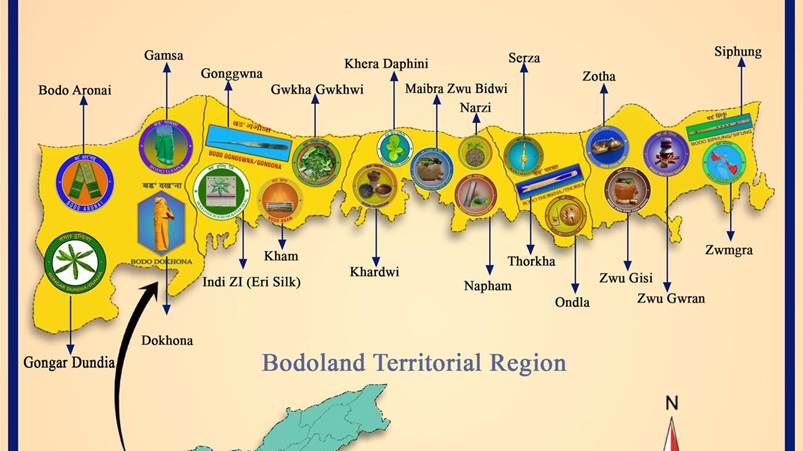

- The Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) government and community groups have secured GI tags for 21 traditional items (Nov 2023–May 2024), covering textiles, musical instruments, beverages, and cuisine.

- A special drive has been launched to secure GI tags for more traditional items of all 26 indigenous communities living in BTR.

- Initiative aligns with cultural preservation, rural development, and the upcoming BTR Council elections (Sept 22, 2025), making GI a key governance and identity issue.

Relevance: GS I (Culture – Tribal Heritage, GI Products), GS II (Governance – Bodo Peace Accord, Identity Politics), GS III (Economy – Rural Development, IPR).

Basics

- Geographical Indication (GI) Tag:

- A form of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) under the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999.

- Identifies goods as originating from a specific territory where quality, reputation, or characteristics are essentially attributable to geography.

- Benefits of GI Tagging:

- Provides legal protection against unauthorized use.

- Enhances market value and export potential.

- Preserves cultural identity and heritage.

- Builds consumer trust by ensuring authenticity.

- Fosters rural development through direct benefits to artisans and farmers.

Comprehensive Overview

Context of BTR Initiative

- BTR spans 8,970 sq. km across five districts bordering Bhutan; governed by the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC).

- The All Bodo Students’ Union (ABSU) had passed a resolution nearly a decade ago to pursue GI tagging of unique Bodo products.

- After the Bodo Peace Accord (2020), Chief Executive Member Pramod Boro prioritized recognition of indigenous heritage, aligning state support with community efforts.

- A youth-led team, including technocrats, artists, and social entrepreneurs, spearheaded the identification and documentation of items.

Items Registered (Nov 2023 – May 2024)

- Textiles: Aronai, Dokhona, Zwmgra (motif-rich designs).

- Musical Instruments: Kham, Serza, Siphung.

- Alcoholic Beverages: Maibra Zwu Bidwi, Zwu Gisi.

- Cuisine: Gwkha Gwkhwi, Napham.

- Others: Gongar Dundia, traditional artefacts.

Inclusive Approach

- Beyond the dominant Bodo community, the drive covers 26 indigenous groups: Adivasis, Gurkhas, Koch-Rajbongshis, Hajongs, Kurukhs, Madahi Kacharis, Hiras, Patnis, etc.

- Supported by Gandhi Hindustani Sahitya Sabha, which trains local scholars and leaders in documentation and filing of GI applications.

- Aim: Establish “GI Villages”, clusters where artisans/farmers receive training, infrastructure, and direct market linkages.

Economic & Socio-Cultural Implications

- Economic Growth: Higher market value and branding of products can boost local incomes, exports, and tourism.

- Rural Development: Direct benefits for artisans and farmers, reducing dependence on middlemen.

- Cultural Preservation: Recognition of textiles, instruments, and food ensures safeguarding of intangible heritage.

- Political Significance: With BTC elections imminent, GI initiative doubles as a governance achievement and identity assertion tool.

- Comparative Example: Similar initiatives in Darjeeling tea, Pochampally Ikat, and Kodaikanal garlic show that GI-tagging can generate global recognition and premium markets.

Challenges Ahead

- Commercialisation Risks: Without adequate marketing and distribution networks, GI tags may remain symbolic.

- Capacity Building: Need for sustained workshops, legal aid, and financial support to communities.

- Global Branding: Translating GI tags into actual export competitiveness requires quality assurance and certification mechanisms.

- Equity Concerns: Ensuring benefits flow to grassroots artisans and not just traders or intermediaries.

The Vanishing Practice of Apatanis

Why in News

- The Apatani tribe of Ziro Valley (Arunachal Pradesh) is witnessing the disappearance of its traditional facial tattoos and wooden nose plugs, once integral to women’s identity.

- The practice was banned in the 1970s due to social stigma and employment barriers, and now survives only among older Apatani women.

- Highlights the tension between cultural preservation and modernization in tribal societies.

Relevance: GS I (Culture – Tribal Traditions, Identity), GS II (Governance – Tribal Rights, Policies), GS III (Society – Modernisation vs Tradition).

Basics

- Community: Apatanis, living in Ziro Valley, Lower Subansiri district, Arunachal Pradesh.

- Geography: Ziro Valley – a UNESCO Tentative World Heritage site, bowl-shaped valley in the eastern Himalayas.

- Cultural Practice:

- Facial Tattoos (Tippei): Done around age 10 by elder women.

- Wooden Nose Plugs (Yaping Hullo): Inserted to make women “less attractive” to invaders; later became a symbol of beauty and tribal identity.

- Ban: Government prohibited the practice in the 1970s, citing social mobility barriers, especially for women seeking urban employment.

Comprehensive Overview

Origins and Evolution

- Protective Origins: Practice began as a strategy to deter abduction of Apatani women by rival tribes and outsiders.

- Cultural Identity: Over generations, it evolved into an honourable symbol of beauty, dignity, and tribal belonging.

- Ritual Process: Carried out during adolescence; nose plugs crafted from forest wood (after cleaning to avoid infection).

Current Scenario

- Decline: Almost vanished among younger generations; now seen only in elderly women.

- Pride vs Modernity: Older women still consider tattoos and plugs integral to being Apatani, while younger generations see them as obstacles to education, employment, and social integration.

- Social Shifts: Globalisation, urban exposure, and inter-community marriage discourage continuation.

Cultural Significance

- Represents unique indigenous aesthetics, differing from mainstream Indian concepts of beauty.

- Acts as a marker of community solidarity and oral history of resilience against external threats.

- Comparable to other indigenous body modification traditions worldwide (e.g., Maori tattoos in New Zealand, Ethiopian lip plates).

Challenges of Preservation

- Government Ban: Initially imposed to promote assimilation and modern opportunities, inadvertently accelerated cultural erosion.

- Generational Gap: Younger Apatanis are ambivalent—balancing pride in heritage with aspiration for modern identity.

- Documentation Needs: Without active recording (photographs, ethnographic studies, digital archiving), the practice risks being lost completely.

Larger Implications

- Anthropological Value: Important case study of how cultural practices transform under pressures of state policy, modernity, and globalization.

- Identity Politics: For many Apatanis, revival or remembrance of this practice ties into broader questions of tribal autonomy and heritage preservation.

- Policy Dimension: Raises debate on whether banning such practices protects or erodes cultural diversity.

- Tourism & Cultural Economy: Ziro Valley’s heritage, festivals (e.g., Ziro Music Festival), and unique traditions can be leveraged for sustainable cultural tourism.