Content

- Transgender-inclusive healthcare in Tamil Nadu

- Holding up GLASS to India; securing stewardship to tackle AMR

- Centre releases draft Seeds Bill; farm outfits cautious, industry welcomes it

- SC bats for protection of pristine sal forest in Jharkhand’s Saranda

- Workplace stress linked to rising cases of diabetes among adults

- Why Hepatitis A deserves a place in India’s Universal Immunisation Programme

Transgender-inclusive healthcare in Tamil Nadu

Why is this in News?

- Article highlights Tamil Nadu’s pioneering model in transgender-inclusive public healthcare.

- Showcases India’s first State-level integration of gender-affirming care into universal health coverage.

- WHO is preparing a global case study (2025) documenting Tamil Nadu’s model.

- Updates on progress: 8 Gender Guidance Clinics (GGCs), 5,200+ enrolments, and 600+ surgeries/hormone procedures under CMCHIS-PMJAY.

Relevance

- GS 2 – Welfare of Vulnerable Sections

Rights of transgender persons; health equity; inclusive public services - GS 2 – Health & Social Justice

Universal Health Coverage; insurance inclusion; role of State governments - GS 2 – Governance & Policy Implementation

State-level innovations; administrative reforms; public service delivery - GS 1 – Society

Gender identity, stigma, discrimination, social inclusion

Basics

- “Leave no one behind” = Core commitment under UN SDGs and Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

- Transgender persons are recognised as a marginalised group needing targeted interventions under:

- Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019

- NHM (Tamil Nadu)

- State Policy for Transgender Persons (2025)

Why do Transgender Persons Face Healthcare Barriers?

- Skill Gaps in Medical Workforce

- Majority clinicians untrained in transgender health.

- Overfocus on STI treatment & surgeries; neglect of preventive, reproductive, geriatric, mental health.

- Structural Exclusion

- Low access to education, formal employment, housing, social security → unstable income & no insurance.

- Discrimination in Healthcare Settings

- Stigma, ridicule, denial of services.

- Fear erodes trust → delayed care, medical complications.

- Documentation Barriers

- Identity mismatch, lack of supportive families, exclusion from ration cards/ID-based welfare.

- Intersectionality Effects

- Health deprivation overlaps with caste, poverty, homelessness.

What Has Tamil Nadu Done?

- 2008: Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital begins gender-affirming surgeries.

- 2008: India’s first Transgender Welfare Board created.

- 2018: NHM establishes Gender Guidance Clinics (GGCs) providing multidisciplinary care.

- 2025: 8 districts now host GGCs with free procedures.

- 2019–2024: 7,644 transgender individuals accessed GGC services.

Services Offered

- Hormone therapy

- Gender-affirming surgery

- Mental health counselling

- STI/HIV services

- Legal/identity support, social linkage

How Has Tamil Nadu Expanded Insurance Coverage?

- 2022: CMCHIS-PMJAY includes gender-affirming surgeries & hormone therapy.

- India = first South Asian country to integrate transgender care under UHC.

- Insurance Partner: United India Insurance Co. (5-year policy 2022–27).

- Advancing PMJAY TG Plus (which offers 50+ procedures):

- TN is 4 years ahead in implementation.

Key Reforms for Accessibility

- Removed income limit of ₹72,000.

- Waived need for ration card with transgender person’s name.

- Addressed exclusion from families, lack of proof, stigma.

Outcomes (as of Oct 2025)

- 5,200+ enrolled under CMCHIS-PMJAY.

- 600+ underwent surgeries/hormone therapy.

- Care provided in 12 empanelled hospitals (public + private).

Policy & Legal Reforms Strengthening the Model

- 2019 Transgender Act (Sec 15): Mandates comprehensive healthcare.

- 2024: NHM trains GGC doctors on WPATH Standards of Care v8.

- Madras High Court Judgments:

- Recognised transgender marriages.

- Mandated curriculum reforms.

- Banned conversion therapy.

- Banned non-consensual intersex surgeries.

- Ordered reopening of GGCs post-COVID.

- Curbed police harassment.

- State Policy Framework

- 2019 TN Mental Health Care Policy

- 2025 State Policy for Transgender Persons: property rights, education, healthcare access.

What Challenges Remain?

- Limited Coverage & Geographical Reach

- Need statewide GGC expansion and district-level continuum of care.

- Lack of Comprehensive Health Manual

- Standard protocols for hormones, surgeries, follow-up, mental health missing.

- Monitoring & Regulation Gaps

- Empanelled hospitals need strong oversight to prevent malpractice/exploitation.

- Mental Health Coverage

- Needs integration into insurance packages; high prevalence of depression, anxiety, violence trauma.

- Provider Competency

- Requires periodic training, certification, accountability mechanisms.

- Grievance Redressal Mechanisms

- Currently weak; community often fears reporting discrimination.

- Limited Research & Data

- Need for State-level epidemiological data on transgender health.

- Persistent Social Prejudice

- Requires cross-sectoral interventions: education, policing, media, families.

- Community Participation

- Policy design, implementation, monitoring must involve transgender-led organisations.

Conclusion

- Tamil Nadu has created India’s most advanced model of transgender-inclusive healthcare with early adoption of gender-affirming services, strong insurance coverage, progressive jurisprudence, and community engagement.

- However, lasting equity requires continuous investment, wider coverage, accountability, and institutionalising transgender persons as partners—not beneficiaries—in the health system.

Holding up GLASS to India; securing stewardship to tackle AMR

Why is this in news?

- WHO released its Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) 2025 report in mid-October 2025.

- India identified as one of the worst AMR hotspots globally.

- Highlights a severe rise in antibiotic-resistant infections, especially in ICUs.

- Kerala’s progress and India’s slow national AMR implementation reignited policy debates.

- Published just ahead of World AMR Awareness Week (18–24 November).

Relevance

- GS 3 – Science & Technology / Biotechnology

Antimicrobial resistance, global surveillance systems (GLASS) - GS 3 – Health & Disease Burden

AMR as a major public health threat; ICU infections; One Health approach - GS 3 – Environment

Pharma effluent regulation, environmental determinants of AMR

Basics

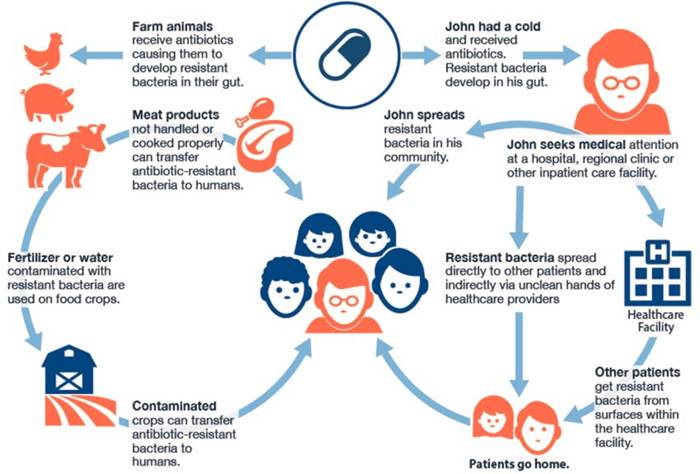

- Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve to resist antibiotics → infections become harder or impossible to treat.

- AMR is driven by human, animal, agriculture, and environmental pathways → a One Health problem.

- GLASS is WHO’s global AMR monitoring system, operational in 100+ countries; India joined in 2017.

Key global findings (GLASS 2025)

- 1 in 6 infections globally resistant to commonly used antibiotics.

- South-East Asia shows the steepest rise; India is disproportionately affected.

- High resistance among critical pathogens: E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus.

- WHO flags a modest but insufficient improvement in the global antibiotic development pipeline.

India-specific findings

- 1 in 3 infections in India in 2023 were antibiotic-resistant.

- Highest resistance burden in ICUs for E. coli, Klebsiella, and MRSA.

- Strong AMR drivers in India:

- Over-the-counter antibiotics

- Self-medication and incomplete courses

- Contaminated pharma effluents and hospital waste

- Weak enforcement of antibiotic regulations

- GLASS notes progress but flags underfunding, uneven surveillance, and weak coordination.

Current efforts in India

- National Programme on AMR Containment.

- ICMR’s AMRSN / i-AMRSS network.

- NCDC’s NARS-Net.

- 2019 ban on colistin in animal feed (significant but long-term impact).

Major weaknesses identified

- Surveillance bias:

- Overdependence on tertiary hospitals → overestimation of AMR; weak data from rural/primary-care settings.

- Underfunding:

- No long-term investment in AMR research, stewardship, or diagnostics.

- Poor One Health coordination.

- NAP-AMR implementation slow:

- 2017 plan remains mostly unexecuted in many States.

- Public awareness extremely low → AMR remains an abstract concept for most Indians.

Expert assessments

Abdul Ghafur

- India’s AMR levels are among the highest globally.

- True national estimates require integrating 500+ NABL labs + primary/secondary hospital microbiology.

V. Ramasubramanian

- Surveillance centres must be geographically spread; without regional representation, conclusions are distorted.

Ella Balasa

- Public needs relatable narratives; humanising AMR is essential for behavioural change.

Antibiotic development pipeline (critical analysis)

Global pipeline trends

- WHO 2024 pipeline report:

- 97 candidates in clinical & preclinical stages (up from 80 in 2021).

- Only 12 of 32 traditional antibiotics are innovative (new class or new mechanism).

- Just 4 candidates target WHO priority MDR Gram-negative pathogens.

India’s status

- CDSCO has approved four new antibiotic candidates in the last two years.

- Six more have global approval.

Limitations

- Pipeline is still too small to address global AMR.

- Limited innovation; low access in LMICs.

- Most new drugs do not target carbapenem-resistant Gram-negatives.

Features needed in next-generation antibiotics

- New mechanisms bypassing current resistance.

- Dual formulations (IV + oral).

- Activity against highest-priority MDR pathogens.

- Safe, affordable, and aligned with stewardship guidelines.

- Low likelihood of inducing further resistance.

Global and industry-side initiatives

AMR Industry Alliance

- Promotes development of new antibiotics and diagnostics.

- Supports responsible antibiotic manufacturing.

- Works on equitable access, especially in LMICs.

Funding gaps

- Surveillance and innovation receive intermittent and inadequate funding.

- Need sustained national investment in AMR research, stewardship, and public awareness.

Kerala model

- Only State with a fully operational AMR State Action Plan.

- Kerala AMR Strategic Action Plan (2018) adopts a strong One Health model.

- AMRITH (2024) stops over-the-counter antibiotic sales.

- State antibiogram shows a slight reduction in AMR levels.

- Goal: antibiotic-literate Kerala by December 2025.

Other significant interventions

- 2019 colistin ban in poultry/livestock → expected long-term benefits.

- Need uniform enforcement across all States.

What India must do (priority recommendations)

Surveillance

- Build a representative national network using NABL labs.

- Strengthen microbiology capacity in district and primary-care hospitals.

Stewardship

- Nationwide ban on OTC antibiotic sales.

- Standardised antibiotic guidelines across hospitals.

- Functional stewardship committees in all tertiary and secondary facilities.

Environment

- Regulate pharma effluents and medical waste.

- Mandatory antimicrobial pollutant monitoring.

Awareness

- Large-scale community orientation on AMR.

- Humanised public campaigns (schools, digital media).

Innovation

- Incentives for new antibiotic classes.

- Academia-industry collaborations.

- Public funding for early-stage R&D.

Governance

- Accelerate implementation of NAP-AMR (2017).

- Strong State-level monitoring and coordination.

Conclusion

- India’s AMR crisis is severe, escalating, and under-monitored.GLASS 2025 reinforces that resistance is rising faster than countermeasures, and progress remains fragmented.

Kerala demonstrates that structured One Health interventions, regulatory enforcement, and public literacy can reduce resistance trends. - India now needs integrated surveillance, strict stewardship, environmental control, innovation incentives, and long-term funding to prevent a future where routine infections again become untreatable.

Centre releases draft Seeds Bill; farm outfits cautious, industry welcomes it

Why in news?

- The Union government has released a new draft Seeds Bill, 2025, after two failed attempts to pass similar legislation in 2004 (UPA) and 2019 (NDA) due to farmer opposition.

- It aims to replace the Seeds Act, 1966 and the Seeds (Control) Order, 1983.

- Government claims alignment with current agricultural and regulatory needs, including seed quality control and liberalised imports.

- Public comments open till December 11.

Relevance

- GS 3 – Agriculture

Seed regulation, quality control, farmer access, seed imports - GS 3 – Economy

Private sector role in seed industry; liberalisation; ease of doing business - GS 2 – Governance / Policy

Legislative reforms; regulatory modernisation; stakeholder conflicts

What are “seeds laws” in India?

- Seeds laws regulate:

- Quality parameters (germination %; genetic purity; physical purity; seed health).

- Certification processes (Indian Minimum Seed Certification Standards).

- Registration of seed dealers and varieties.

- Liability for seed failure.

- The Seeds Act, 1966 is considered outdated:

- Focused on public-sector dominance.

- Lacks frameworks for modern hybrids, GM events, private R&D, and global seed trade.

Key provisions of the draft Seeds Bill, 2025

- Mandatory registration:

- Every seed dealer must register with the State government before selling or exporting/importing seeds.

- Quality regulation:

- Seeds sold must meet minimum certification standards for germination, purity, traits, health.

- Regulation of sale to ensure declared performance.

- Liberalisation:

- Greater freedom for seed imports, enabling access to global varieties.

- Decriminalisation:

- Minor offences decriminalised to reduce compliance burden.

- Serious violations retain strong penalties.

- Farmer protection:

- Ensures farmers’ access to high-quality seeds at affordable rates.

- Aims to prevent losses due to substandard seeds.

Why earlier attempts (2004 and 2019) failed

- Farmer groups opposed:

- Mandatory registration and certification seen as restricting farmer-saved seeds.

- Fear of greater corporate control over the seed market.

- Concerns around liability provisions favouring companies.

- Bills were withdrawn after widespread protests, especially in Punjab, Haryana, Maharashtra, Telangana.

Farmers’ perspective

- Seen as industry-friendly:

- “Bill favours seed companies and facilitates ease of doing seeds business” (BKU-Ekta Ugrahan).

- Key concerns:

- Could lead to higher seed prices.

- Risk of monopolisation by MNCs/private breeders.

- Stronger regulation might apply more to farmers than companies.

- Fear of indirect control over farmer-saved and exchanged seeds via registration norms.

Seed industry perspective

- Welcomed as a modernising move, especially by the Federation of Seed Industry of India.

- Benefits to industry:

- Clearer regulatory regime.

- Decriminalisation reduces business risk.

- Liberalised imports expand breeding and hybridisation possibilities.

- Predictability for private investment.

Larger policy context: why regulate seeds more tightly now?

- India’s seed market size: ₹25,000–27,000 crore; private sector share: 65–70%.

- Issues:

- Quality failures cause 10–30% yield loss depending on crop.

- Spurious seeds cases frequently reported in cotton, paddy, vegetables.

- Need to integrate global seed variety testing, DUS criteria, and digital traceability.

Critical analysis

Strengths

- Modernises a 60-year-old law.

- Better consumer protection through quality benchmarks.

- Enables innovation and global germplasm flow.

- Rationalises penal provisions → encourages private R&D.

Concerns

- May unintentionally promote corporate dominance in seeds.

- Registration rules could affect:

- farm-saved varieties,

- community seed systems.

- Liberalised imports risk entry of high-cost foreign varieties → price inflation.

- No clarity on seed liability and compensation mechanisms — historically the most contentious aspect.

- Risk of conflict with:

- PPV&FRA, 2001 (farmers’ rights),

- Biodiversity Act, 2002 (access to genetic resources).

Governance risks

- States’ capacity to run robust registration and testing systems remains weak.

- Enforcement uneven across India → inconsistent protection for farmers.

SC bats for protection of pristine sal forest in Jharkhand’s Saranda

Why in news?

- The Supreme Court has directed the Jharkhand government to declare 31,468.25 hectares (314 sq. km.) of the Saranda forest as a wildlife sanctuary.

- This ends the State’s reluctance and its earlier proposal to declare only 24,941.64 hectares due to concerns over mining and infrastructure.

- The court emphasised the State’s constitutional duty to protect ecologically significant areas and balance conservation with sustainable mining.

Relevance

- GS 3 – Environment & Biodiversity

Sal forest ecosystem; wildlife sanctuary declaration; threatened species - GS 3 – Conservation vs Development

Mining–ecology conflict; sustainable mining; iron ore reserves - GS 2 – Judiciary / Constitutional Provisions

Public trust doctrine; State’s duty to protect forests

Basics: where and what is Saranda?

- Location: West Singhbhum district, Jharkhand.

- Known as one of the world’s most pristine sal forests.

- Ecological features:

- Dominant sal (Shorea robusta) ecosystem.

- Home to endemic sal forest tortoise, four-horned antelope, Asian palm civet, wild elephants.

- Social context:

- Inhabited for centuries by Ho, Munda, Uraon and allied Adivasi communities.

- Livelihoods deeply tied to minor forest produce and cultural traditions.

Why is the area contentious?

- Saranda forest division also contains 26% of India’s iron ore reserves.

- SAIL and Tata Steel depend critically on mining in this region.

- Judicial declaration of the entire 314 sq. km. as a sanctuary could:

- Restrict or reshape mining operations.

- Affect employment in mining-linked areas.

- Require reevaluation of several leases.

Key observations of the Supreme Court

- State’s duty:

- Forests and wildlife must receive statutory protection where ecologically significant.

- The State cannot “run away from its duty to declare” such areas.

- Balanced approach:

- Conservation must coexist with sustainable iron ore mining, not eliminate it.

- Sanctuary notification does not automatically extinguish tribal rights.

- Community protection:

- Court directed mass communication that individual and community forest rights under FRA, 2006 will not be adversely affected.

- Ecological significance:

- Court stressed the unique sal ecosystem, biodiversity richness, and presence of threatened species.

Government’s position (as per hearings)

- Initially proposed declaring only 24,941.64 hectares due to:

- “Vital public infrastructure” in the remaining area.

- Concerns about halting mining.

- Later clarified:

- The 31,468.25 hectares being considered had no mining, no non-forest use, and no prior diversion.

- After the court’s push, the government agreed to proceed with full notification.

Ecological significance

- Saranda is a high-integrity sal landscape—rare globally.

- Functions as a critical elephant habitat and corridor.

- Sanctuary status ensures:

- Stricter protection under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972.

- Better control over fragmentation from roads, mining, and encroachments.

Mining–conservation tension

- Region’s mineral value is extremely high (26% national iron ore).

- Conservation imperatives clash with:

- Employment generation.

- Steel sector supply chains.

- Local economic activity.

- Court’s directive pushes for “sustainable mining + strict ecological zoning” rather than blanket bans.

Tribal rights and welfare

- FRA, 2006: Sanctuary notification cannot extinguish existing rights.

- Court acknowledged:

- Tribes are ecosystem stakeholders.

- Sanctuary declaration must not lead to displacement.

- Important shift from earlier models of exclusionary conservation.

Governance implications

- Sets a precedent:

- States must declare ecologically important areas even if economically sensitive.

- Strengthens judicial oversight over forest governance.

- Enhances application of:

- Precautionary principle

- Public trust doctrine

- Requires integrated landscape planning for:

- Mining zones

- No-go biodiversity zones

- Community rights areas

Workplace stress linked to rising cases of diabetes among adults

Why in news?

- New clinical observations and emerging Indian research show a sharp rise in workplace-stress–linked Type 2 diabetes, especially among young urban working adults.

- Doctors report increasing cases among tech, finance, customer service, healthcare and night-shift workers.

- The report is released in the context of World Diabetes Day, highlighting stress as a major but under-recognised metabolic risk factor.

Relevance

- GS 3 – Health / NCDs

Stress-induced Type 2 diabetes; metabolic disorders; India’s disease burden - GS 3 – Economy / Labour

Workplace wellness, productivity loss, occupational health risks - GS 1 – Society

Changing work culture; lifestyle transitions; urbanisation impacts

Basics: what is stress-linked diabetes?

- Prolonged workplace stress → chronic activation of cortisol and adrenaline.

- These hormones:

- Raise blood glucose

- Reduce insulin sensitivity

- Increase central (abdominal) fat

- Disrupt circadian rhythm (especially in shift workers)

- Result: Insulin resistance → pre-diabetes → Type 2 diabetes.

What the data shows ?

- India: 10.1 crore diabetics (ICMR–INDIAB, 2023).

- Tamil Nadu study: higher perceived stress = poorer glycaemic control + longer disease duration.

- Hospitals in Chennai & Bengaluru report earlier onset (30s–40s) even without excess dietary intake.

Clinical observations

Early metabolic signs (often ignored as “busy life”)

- Abdominal weight gain

- Daytime fatigue

- Fragmented sleep

- Increased cravings

- Borderline BP

- Mildly elevated triglycerides

- Rising post-meal sugars

Why they worsen unnoticed

- Normalisation of long work hours

- Sleep deprivation

- Irregular meals

- Sedentary desk culture

- High device dependence and constant “on-call” pressures

Why certain professions are high-risk

IT, Finance, Customer Support

- Long screen hours

- High cognitive load

- Deadline cycles

- Constant notifications

- Guilt about switching off devices

Healthcare

- Emotional labour + erratic schedules

Night-shift workers

- Circadian rhythm disruption

- Irregular meals → reduced insulin sensitivity

- Higher glucose variability despite good diet adherence

Pathophysiology: how stress translates to diabetes

- Chronic stress → persistent HPA axis activation.

- Elevated cortisol:

- Increases hepatic glucose output

- Promotes visceral fat accumulation

- Reduces muscle glucose uptake

- Adrenaline surges:

- Fluctuating post-meal sugars

- Sleep disruption

- End result: progressive insulin resistance.

Doctors’ insights from multiple hospitals

- More young adults (29–45 years) showing central obesity + borderline sugars.

- Women show higher incidence of stress-linked metabolic changes in recent studies.

- Many patients discover diabetes incidentally through routine tests.

- Stress management improves glycaemic stability even in medicated patients.

Workplace factors driving the trend

- No scheduled lunch breaks

- Prolonged sitting

- Excessive meeting loads

- Late-night logging

- Shift rotation gaps

- Poor sleep hygiene

- High job insecurity

- Multitasking pressure

Evidence-backed low-cost interventions

For workplaces

- Protected lunch breaks

- 5–10 minute movement gaps between meetings

- Restrictions on after-hours work communication

- Healthier cafeteria menus

- Predictable shift rotations

For individuals

- 7–8 hours sleep

- Mindfulness/therapy

- Structured daily routines

- Consistent meal timings

- Device-free downtime

- Walking meetings / micro-activity

Doctors emphasise: “Stabilising cortisol stabilises blood sugar.”

Overview

Public health significance

- Stress-linked diabetes is emerging as a non-traditional risk factor.

- Shifts diabetes from being purely lifestyle-driven to occupational-environment–driven.

- Raises concerns for India’s young workforce and productivity.

Economic implications

- Higher absenteeism and presenteeism

- Rising corporate healthcare costs

- Long-term burden on insurance systems

- Earlier onset → longer disease duration → higher complications

Gender dimension

- Women face dual stress exposures: workplace + unpaid care work.

- Increasing evidence of higher pre-diabetes progression rates in women under occupational stress.

Policy relevance

- Need for integration of occupational health within NCD programmes.

- Shift work regulation and circadian-friendly policies.

- Mandatory workplace wellness norms for high-risk sectors.

Behavioural challenge

- Stress is intangible → symptoms normalised.

- Requires awareness + employer accountability + clinical screening.

Why Hepatitis A deserves a place in India’s universal immunisation programme

Why in news?

- India is debating including the Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine (TCV) in the Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP).

- Experts argue that Hepatitis A vaccination deserves even higher priority because the disease burden is shifting toward adolescents and adults — groups at significantly higher risk of severe disease, including acute liver failure.

- The article highlights that an effective indigenous Hepatitis A vaccine exists, yet policy inclusion is pending.

Relevance

- GS 2 – Health / Immunisation

UIP expansion; vaccine policy; epidemiological transition - GS 3 – Public Health

Outbreak management; sanitation transition; acute liver failure - GS 2 – Governance & Policy

Evidence-based policymaking; cost-effectiveness; indigenous vaccine development

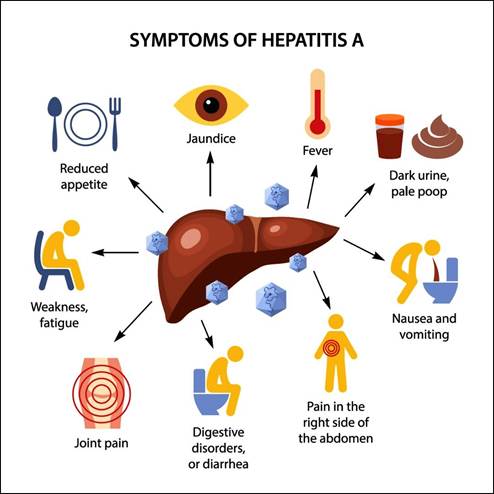

Basics: what is Hepatitis A?

- Acute viral liver infection typically mild in young children.

- Historically: >90% Indians exposed in childhood → lifelong immunity.

- Current shift: improved sanitation → fewer children infected early → more susceptible adolescents & adults.

- Severe disease in older age groups → acute liver failure, hospitalisation, deaths.

- No specific antiviral treatment → only supportive care.

Changing epidemiology

- Seroprevalence (protective antibodies) dropping from ~90% to <60% in many urban regions.

- Outbreaks reported in Kerala, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi.

- Clusters of acute liver failure in hospitals show rising severity.

- Hepatitis A now an emerging public-health threat, not a benign childhood disease.

Hepatitis A vs Typhoid: key contrasts

Disease burden

- Typhoid mortality declining with antibiotics + sanitation.

- Hepatitis A rising in older children/adults → more severe outcomes.

Treatment

- Typhoid: antibiotics available; AMR emerging but treatable.

- Hepatitis A: no specific treatment, recovery depends entirely on supportive care.

Vaccine characteristics

- Hepatitis A vaccines:

- 90–95% efficacy

- Single dose for live vaccine

- Long-lasting (15–20 years to lifelong)

- No issues of waning immunity or resistance

- Typhoid vaccines: require multi-dose cycles in some settings; immunity relatively shorter.

Programmatic simplicity

- Hepatitis A vaccine is single-dose, easy to integrate with existing booster schedules.

- Indigenous product (Biovac-A by Biological E) has two decades of excellent use in private sector.

Cost-effectiveness

- Hepatitis A: high-cost outbreaks, expensive hospitalisation, severe disease in adults → strong economic rationale for universal vaccination.

- Typhoid: important but lower immediate cost-effectiveness because mortality has declined.

Why Hepatitis A deserves priority

- Growing susceptible population: fewer children infected early → rising young adult vulnerability.

- Severe disease profile: adult infection = higher hospitalisation + acute liver failure risk.

- No treatment: prevention via vaccination is the only effective shield.

- Low-hanging fruit:

- Single dose

- Long-term immunity

- Indigenous supply available

- Clear scientific evidence: declining antibodies + frequent outbreaks.

Recommended strategy for India

- Adopt a phased introduction, aligned with UIP’s proven approach:

- Start with States facing repeated outbreaks or low seroprevalence.

- Co-administer with DPT or MR boosters to use existing systems.

- Conduct periodic serosurveys to monitor immunity levels.

- Gradually expand to national scale.

Public health rationale

- Fits UIP tradition of proactive shifts (Hepatitis B, Rotavirus, Pneumococcal).

- Helps prevent avoidable severe disease and hospital burden.

- Reduces long-term healthcare costs by preventing liver complications early.

Overview

Epidemiological relevance

- The shift from early childhood exposure to adolescent vulnerability reflects India’s sanitation transition.

- Parallel seen previously in East Asia and Latin America before they introduced universal Hepatitis A vaccination.

- Without vaccination, India risks repeated outbreaks and rising adult mortality from acute liver failure.

Programmatic feasibility

- Single-dose administration makes planning efficient.

- Indigenous production ensures supply security and affordability.

- Can be rapidly scaled using existing UIP logistics.

Economic considerations

- Adult hospitalisations for Hep A are expensive (ICU care, liver monitoring, long recovery).

- Vaccination cost per child is low compared to treatment cost.

- Higher workforce productivity because adults are protected.

Policy gap

- Scientific consensus is strong, but policy action is lagging, unlike for TCV where debate is ongoing.

- No technical barrier: the missing piece is only political and administrative decision-making.