Content

- Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM)

- Nominated Members in Legislatures

- Toll Collection Practices in India

- Ethanol Blending in Petrol

- Creamy Layer in OBC Reservation

- Nationalists in Ireland, India: How a Future Indian President was Inspired

The Disease: Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM)

- Causative Agent:

- Caused by Naegleria fowleri (a free-living, thermophilic amoeba).

- Commonly found in warm freshwater (ponds, lakes, poorly maintained swimming pools, stagnant water).

- Mode of Transmission:

- Amoeba enters the human body through the nose while swimming, bathing, or diving in contaminated water.

- Reaches the brain through the olfactory nerve (cribriform plate).

- Not transmitted person-to-person.

- Pathophysiology:

- Amoeba invades the central nervous system → acute inflammation of brain and meninges.

- Causes Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM) → often fatal.

Relevance : GS 2(Health), GS 3(Science and Technology)

Symptoms & Clinical Course

- Incubation period: 5–10 days after exposure.

- Early Symptoms:

- Severe headache, fever, nausea, vomiting.

- Stiff neck, photophobia (light sensitivity).

- Children: refusal to eat, irritability, lethargy.

- Progressive Symptoms:

- Confusion, altered behavior.

- Seizures, epilepsy.

- Memory loss, fainting.

- Coma → death (usually within 1–2 weeks of symptom onset).

- Mortality: Extremely high (95–99%), with very few survivors globally.

Risk Factors

- Swimming or bathing in stagnant or warm freshwater (especially during summer).

- Children at higher risk (due to thinner cribriform plate → easier entry to brain).

- Ear/nose surgeries or injuries may increase susceptibility.

- No risk from drinking contaminated water (infection occurs only through nose).

Recent Outbreak in Kerala

- Kozhikode (2024): 3 cases detected, 1 death reported.

- Previous local outbreaks in Kerala had led to warning boards near ponds to alert public.

- Current alert: Issued by Kerala Health Department to raise awareness and encourage precaution.

Preventive Measures

- Avoid swimming or bathing in stagnant/unclean ponds, lakes, and warm water bodies.

- Use nose clips while swimming to prevent water entry.

- Ensure chlorination and cleaning of public water sources and swimming pools.

- People with nasal/ear surgeries should avoid exposure to stagnant water.

- Public awareness campaigns: leaflets, boards near ponds, media outreach.

Treatment Challenges

- No single guaranteed cure.

- Drugs used (in combinations):

- Amphotericin B, Miltefosine, Azoles (Fluconazole, Ketoconazole).

- Treatment effective only if started very early.

- Supportive care (ICU, ventilator support) often required.

Broader Public Health Concerns

- Rarity but Deadliness: Cases are rare, but nearly always fatal → high fear factor.

- Climate Change Link: Rising temperatures and water stagnation may increase risk.

- Surveillance & Rapid Diagnosis:

- Need early identification at hospitals.

- Train health workers to recognize neurological symptoms after water exposure.

Bottom Line:

- PAM is a rare but almost always fatal brain infection caused by Naegleria fowleri.

- Kerala’s alert in Kozhikode is precautionary due to recent cases and a death.

- Preventive steps (avoiding stagnant water, using nose clips, awareness campaigns) are critical, as treatment options are limited and survival rates are very low.

Nominated Members in Legislatures

Constitutional Provisions:

- Parliament: 12 nominated members in Rajya Sabha (by President on aid & advice of Union Council of Ministers).

- State Assemblies: Earlier, Governors nominated one Anglo-Indian MLA (now abolished in 2020).

- Legislative Councils: Nearly 1/6th of members are nominated by Governors (on advice of State Council of Ministers).

- Principle:

- Nomination exists to bring in experts, minority/community representation, or to supplement elected members.

- But always on aid & advice of elected executive, ensuring accountability.

Relevance : GS 2(Polity and Constitution)

Union Territories with Assemblies

- Delhi (GNCTD Act, 1991):

- 70 elected MLAs, no nominated members.

- Puducherry (Government of UT Act, 1963):

- 30 elected MLAs + up to 3 nominated by Union government.

- Controversy: Union govt nominates directly, bypassing UT Council of Ministers.

- J&K (J&K Reorganisation Act, 2019, amended 2023):

- 90 elected seats.

- LG may nominate up to 5 members:

- 2 women,

- 2 Kashmiri migrants,

- 1 displaced person from Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

Case Law & Judicial Rulings

- Puducherry (K. Lakshminarayanan v. Union of India, 2018 – Madras HC):

- Held: Union govt can nominate 3 MLAs to Puducherry Assembly without UT Cabinet advice.

- Recommended statutory clarity, but Supreme Court later set aside these recommendations.

- Delhi (GNCTD v. Union of India, 2023 – SC Constitution Bench):

- Introduced “Triple Chain of Command” principle:

- Civil servants accountable to Ministers.

- Ministers accountable to Legislature.

- Legislature accountable to People.

- Ensures democratic accountability → LG bound by aid & advice of Council of Ministers (except in subjects outside Delhi Assembly’s legislative domain).

- Though about services, rationale extends to nominations: LG should act with Cabinet’s advice to maintain democratic chain.

- Introduced “Triple Chain of Command” principle:

Current Controversy: J&K

- Union Home Ministry’s stand (2024 affidavit):

- LG can nominate 5 members without aid & advice of J&K Council of Ministers.

- Democratic Concerns:

- Risks undermining popular mandate, especially in a small Assembly (90 elected).

- Nominated MLAs can swing majority/minority balance → undemocratic if done by Union govt/ LG alone.

Why It Matters

- Federal Balance:

- UTs with Assemblies (Delhi, Puducherry, J&K) are hybrid — not full States, but with elected governments.

- Direct Union control via LG nominations risks weakening local democracy.

- Political Neutrality:

- When ruling party at Centre ≠ ruling party in UT, nomination power can be weaponised to influence Assembly outcomes.

- J&K’s Special Case:

- Was a State till 2019, with even greater autonomy.

- SC upheld reorganisation, but Govt assured early restoration of statehood.

- Therefore, democratic principles must be safeguarded → LG should nominate only on Cabinet advice.

Way Forward: How Should Nominations Be Done?

- For J&K Assembly:

- LG should exercise power only on aid & advice of UT Council of Ministers (once elected).

- Aligns with SC’s triple chain of command principle.

- Prevents manipulation of Assembly arithmetic.

- For Puducherry Assembly (Govt of UT Act, 1963):

- Parliament should amend law to mandate that Union govt/ LG act on UT Cabinet’s advice.

- Brings practice in line with democratic accountability.

- For All UTs with Assemblies:

- Clear statutory framework on:

- Who nominates,

- On whose advice,

- Criteria for nomination (minorities, women, expertise).

- Prevents arbitrary use of nomination powers.

- Clear statutory framework on:

Bottom Line:

- Who decides nominations? → Constitutionally, nominations are made by President/Governors/LGs, but always on aid & advice of elected governments (except where law explicitly allows Centre’s discretion).

- J&K Assembly nominations should be by LG on advice of Council of Ministers, to preserve democracy.

- Puducherry (1963 Act) allows Union govt direct nomination (problematic).

- SC’s 2023 “Triple Chain of Command” principle reinforces that unelected authorities (LG, Union govt) should not bypass elected executives in democratic functioning.

Toll collection practices in India

Basics of Toll Collection

- Legal Basis:

- National Highways Act, 1956 → empowers GoI to levy fees (Section 7) and make rules (Section 9).

- Current framework: National Highways Fee (Determination of Rates and Collection) Rules, 2008.

- Models of Collection:

- Publicly funded highways → toll collected by GoI/NHAI.

- Build Operate Transfer (BoT) → concessionaire collects till investment recovered + concession period.

- Toll-Operate-Transfer (ToT) / InvIT models → private players operate & collect toll.

- Fee Structure:

- Base rates fixed in 2008.

- Escalation: +3% annually + 40% of WPI increase.

- Not linked to actual cost recovery or quality of service.

- Revenue Trend:

- ₹1,046 crore (2005–06) → ₹55,000 crore (2023–24).

- Of this, ~₹25,000 crore goes to Consolidated Fund of India, balance to concessionaires.

- Toll is now seen as a perpetual revenue stream, not just cost-recovery.

Relevance : GS 2(Governance)

Problems in Current Tolling Regime

- Perpetual Tolling:

- Even after capital costs are recovered, tolling continues indefinitely (due to 2008 amendment).

- Creates “double taxation” feeling since users also pay high road/cess on fuel.

- Transparency Issues:

- No independent authority to evaluate if toll rates are justified.

- Annual hikes are automatic, not linked to road quality, maintenance, or service delivery.

- Equity Concerns:

- Toll is a regressive tax: affects poorer daily commuters disproportionately.

- No concessions during road expansion/construction phases, despite reduced usability.

- Operational Inefficiencies:

- FASTag rollout improved things, but queues persist due to:

- faulty scanners,

- insufficient lanes,

- inadequate top-up/recharge facilities on site.

- FASTag rollout improved things, but queues persist due to:

- Trust Deficit:

- Users perceive toll as a permanent government rent rather than a genuine cost-recovery mechanism.

Key PAC Recommendations

- End Perpetual Tolling:

- Toll should end once project cost + O&M costs are recovered.

- Any extension must be justified and approved by a new independent regulator.

- Independent Regulatory Authority:

- Oversee toll determination, collection, and escalation.

- Ensure fair pricing, transparency, and accountability.

- Reimburse Users During Construction:

- If widening/repair work disrupts traffic, commuters should get reduced or refunded toll.

- Reform Escalation Formula:

- Move beyond flat +3% + partial WPI indexation.

- Link hikes to actual O&M costs, road quality benchmarks, and vehicle operating costs.

- Improve FASTag Functionality:

- On-location services at plazas for recharge/replacement.

- Address scanner and connectivity issues to reduce congestion.

Global Comparisons

- Developed Economies:

- US, EU → tolls are typically project-specific, end after debt recovery, or replaced by road-use taxation.

- Transparent public audits of toll revenues.

- China:

- Heavily tolled network; clear sunset clauses after debt recovery, though extension common in practice.

- Brazil & Mexico:

- Mixed concession models but linked to service guarantees (lane availability, safety, emergency services).

India’s perpetual tolling model is more revenue-driven than service-driven.

Science & Economics of Tolling

- Economic Rationale:

- User-pays principle → those who benefit should pay.

- Efficient in theory but inequitable in practice if poorly regulated.

- Issues with Perpetual Tolling:

- Becomes a hidden tax beyond cost recovery.

- Erodes public trust → leads to evasion, protests, and resistance.

- Technology Solutions:

- GPS-based tolling (already piloted in EU, Singapore): pay-per-km, avoids bottlenecks, fairer distribution.

- Dynamic pricing based on congestion and road quality.

Way Forward: Suggested Reforms

- Policy Reforms:

- Roll back perpetual tolling amendment.

- Legally mandate sunset clauses post cost-recovery.

- Mandate value-for-money audits of highways.

- Institutional Reform:

- Independent toll regulator under NHAI/NITI Aayog.

- Public reporting of toll revenue, O&M expenditure, debt repayment.

- Technological Reform:

- GPS-based tolling to replace physical plazas (reduces leakage & congestion).

- Full FASTag integration with seamless top-up, auto-deductions, digital complaint redressal.

- Equity Safeguards:

- Discounts for frequent commuters, public transport, and local residents.

- Temporary toll suspension or reduction during construction phases.

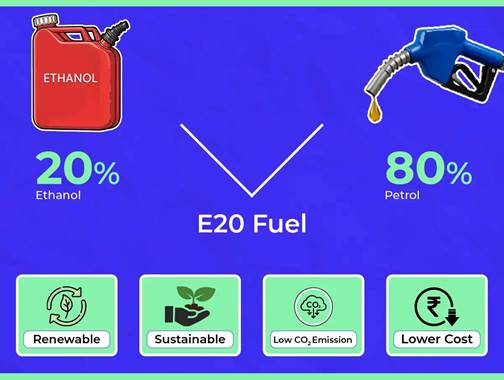

Ethanol Blending in Petrol

Context and Policy Goals

- Govt. target: 20% ethanol blending (E20) by 2025.

- Objectives:

- Energy security → reduce crude oil imports (India imports ~85% of crude needs).

- Carbon emission reduction → lower GHGs.

- Rural income boost → new market for sugarcane, maize, rice, and agricultural residues.

- Waste utilisation → use of damaged food grains and crop residues.

Relevance : GS 3(Environment and Ecology , Science and Technology)

Scientific Basis of Ethanol

- Nature: Ethanol (C₂H₅OH) – an oxygenated biofuel.

- Production:

- From sugarcane/molasses via yeast fermentation.

- From food grains (maize, rice, broken grains).

- From lignocellulosic biomass (non-food crop residues – cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin).

- Process:

- Sugars → glucose (invertase) → ethanol + CO₂ (zymase).

- Key property: Hygroscopic (absorbs water), influencing corrosion and storage.

Energy Efficiency of Ethanol vs Petrol

- Calorific Value (CV):

- Petrol: ~43 MJ/kg.

- Ethanol: ~27 MJ/kg (≈35% lower).

- Implication → lower mileage per litre.

- Octane Number (ON):

- Petrol: 87–91.

- Ethanol: ~108.

- Higher ON → better resistance to knocking, smoother combustion.

- Net Result:

- Slight mileage drop at E20 (~2–4%).

- Noticeable only at E100 (100% ethanol).

Vehicle Impact – Scientific Concerns

- Hygroscopic Effect:

- Water absorption → rusting of tanks, clogging of fuel lines, reduced efficiency.

- Material Compatibility:

- Ethanol corrodes rubber and plastic components in older vehicles (fuel pipes, gaskets, injectors).

- Stoichiometric Ratio (Air–Fuel mix):

- Ethanol adds oxygen → alters combustion chemistry.

- Requires recalibration of spark timing and ECU (Electronic Control Unit).

- Engine Types:

- Modern BS-IV & BS-VI vehicles (post-2020): ECU-controlled → can adapt to E20.

- Older carbureted vehicles (pre-2020): No ECU → cannot be retrofitted easily.

Environmental & Emission Effects

- Positives:

- Reduced CO, NOx, and particulate emissions due to oxygen-enriched combustion.

- Lower lifecycle CO₂ if biomass sustainably sourced.

- Negatives:

- Land-use shift → possible diversion of food crops to fuel.

- High water footprint of sugarcane → aggravates groundwater depletion.

- Possible indirect emissions from fertilisers, transport, and processing.

Maintenance and Cost Concerns

- Govt. claim: Only one-time replacement of rubber components needed.

- Experts’ warning:

- Corrosion more severe in cold regions (moisture condenses).

- Regular servicing and higher maintenance costs inevitable for older vehicles.

- Recalibration of engines → increases manufacturing cost for auto industry.

International Experience

- Brazil:

- Started in 1970s (Proálcool programme).

- Currently runs on E27 + widespread use of flex-fuel vehicles.

- Transition was gradual, with subsidies, infrastructure, and farmer-industry linkages.

- USA:

- Large-scale corn ethanol production, but criticized for food vs fuel conflict.

- India’s challenge: Compressed timeline (2021 → 2025), unlike Brazil’s decades-long transition.

Science-Driven Challenges for India

- Agronomic:

- Heavy reliance on sugarcane → water-intensive (3,000–5,000 litres water per litre ethanol).

- Risk of food vs fuel diversion if maize/rice used extensively.

- Technological:

- Lack of widespread flex-fuel engine technology.

- Insufficient 2G ethanol production (from agri-waste).

- Infrastructure:

- Ethanol blending needs separate pipelines/storage tanks (due to hygroscopic nature).

- Higher transport costs for ethanol from rural production sites to refineries.

- Economic:

- High production cost of ethanol vs subsidised petrol.

- Fiscal burden of incentives/subsidies to sugar mills & distilleries.

Scientific Verdict

- Strengths:

- Cleaner combustion (less CO, PM).

- Energy diversification, import reduction.

- Adds rural economic value, waste-to-fuel potential.

- Weaknesses:

- Lower energy density → mileage drop.

- Corrosion/moisture issues in older vehicles.

- Water-intensive crops (sugarcane).

- Limited readiness of Indian vehicles for E20.

Way Forward

- Diversify feedstock: Promote 2G ethanol (crop residues, agri-waste, bamboo).

- Technology adoption: Encourage flex-fuel vehicles (as in Brazil).

- Agricultural reforms: Shift away from water-guzzling sugarcane → maize, sorghum, cellulosic biomass.

- Infrastructure: Invest in ethanol storage, blending, distribution systems.

- Policy pacing: Gradual transition (E10 → E12 → E15 → E20) with simultaneous vehicle adaptation.

- R&D push: Develop corrosion-resistant materials and better engine calibration technologies.

Creamy Layer in OBC Reservation – Debate on “Equivalence”

Basic Concepts

- Reservation in India:

- Based on Articles 15(4), 16(4), and 340 (Constitution) → for socially and educationally backward classes (SEBCs), SCs, and STs.

- Aim: Correct historical injustices, ensure representation in education, employment, and politics.

- Creamy Layer (CL):

- Concept introduced by Indra Sawhney Case (1992).

- Ruling: Reservation benefits should not go to the “advanced sections” among OBCs, i.e., those with higher income, social capital, or government positions.

- Purpose: Ensure benefits reach the most disadvantaged, not the relatively privileged within OBCs.

Relevance : GS 2(Governance ,Social Issues)

Indra Sawhney Judgment (1992)

- Upheld 27% OBC reservation as per Mandal Commission.

- Directed exclusion of “creamy layer”:

- Children of high-ranking officials, professionals, industrialists, etc.

- Applied only to OBCs, not SCs/STs.

- Set income/position-based tests for exclusion.

DoPT Guidelines (Post-1993)

- Income threshold set at ₹1 lakh annually (1993).

- Revised multiple times → now ₹8 lakh per year (since 2017).

- Categories excluded:

- Children of Group A/All India Services officers.

- Children of armed forces officers above Lt. Colonel.

- Professionals/business owners with substantial income.

- Importantly: Wealth (property ownership) is not considered, only income/profession.

Issues in Implementation

- Anomalies:

- Children of low-paid Group A officers automatically excluded (though not necessarily “affluent”).

- Children of public sector employees treated differently from private-sector counterparts.

- Lack of uniformity across state vs central services, teaching vs non-teaching posts.

- Certificates issued under old criteria sometimes still used, even after revisions.

- Court rulings in 2015 & 2023 highlighted confusion and inconsistencies.

Current Proposal: “Equivalence”

Aim → uniform criteria across ministries, PSUs, universities, and states.

- Key Features Proposed:

- Equivalence of Pay Scales: Link OBC creamy layer exclusion to pay level (not just income).

- Eg. Assistant Professors (entry-level university teachers) = Group A equivalent → counted in creamy layer.

- Non-teaching staff in universities: Equated with state government non-teaching positions.

- Executives in PSUs:

- If income > ₹8 lakh, they fall under creamy layer.

- But ceiling for private sector employees = ₹8 lakh income, irrespective of position.

- Employees of government-funded institutions: Should follow same service rules/pay-scales as government employees.

- Equivalence of Pay Scales: Link OBC creamy layer exclusion to pay level (not just income).

Likely Beneficiaries

- Children of lower-rank Group A officers (earning just above ₹8 lakh but not wielding high social capital).

- Employees of state universities & aided institutions who previously faced unequal treatment.

- OBC candidates denied earlier due to lack of uniform application of creamy layer norms.

Broader Analysis

- Positive Aspects:

- Creates fairness, removes anomalies.

- Prevents arbitrary exclusion.

- Ensures genuine backward classes continue benefiting.

- Concerns:

- Income ceiling (₹8 lakh) may still be too high, letting affluent OBCs corner benefits.

- Wealth/property ownership still ignored.

- Equivalence across diverse institutions (state, PSU, universities) is administratively complex.

- Risk of dilution of merit vs social justice balance.

Policy & Political Dimensions

- Creamy layer debate often resurfaces during elections → political sensitivity.

- Expanding creamy layer definition = balancing act between social justice and appeasing middle-class OBCs.

- Recommendations by NCBC, DoPT, and Social Justice Ministry under discussion.

Comparative Insights (Global)

- US: Affirmative action debates also face “class vs race” questions (should rich Black families get same benefit as poor?).

- South Africa: Similar debates on whether upper-class Black Africans should benefit from racial quotas.

- India’s creamy layer = unique model of mixing caste + class filters.

Way Forward

- Regular revision of income ceiling linked to inflation.

- Include wealth/property criteria, not just income.

- Separate criteria for rural vs urban OBCs.

- Improve data transparency in issuance of creamy layer certificates.

- Gradually shift towards socio-economic deprivation index (composite indicators).

Nationalists in Ireland, India: How a Future Indian President was Inspired

Basic Background

- Who: Varahagiri Venkata Giri (V.V. Giri) – 4th President of India (1969–1974).

- Where: Studied law in Dublin (1913–1917).

- Context: Ireland under British rule → parallel anti-colonial movements in Ireland and India.

- Link: Giri’s exposure to Irish labour movement, nationalist struggle, and student activism shaped his political ideology in India.

Relevance: GS 1(History )

Conditions in Ireland (Early 20th Century)

- Admission for Indians in English universities stricter → Ireland relatively more open.

- Racial prejudice less pronounced in Ireland compared to Britain.

- Dublin = hub of student, labour, and nationalist movements.

- Dublin Lockout (1913): workers’ strike against exploitation → Giri directly witnessed.

Giri’s Activism in Dublin

- Immersed in Irish Labour Movement → exposure to collective bargaining, trade unionism.

- Inspired by:

- Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union.

- Radical leaders like James Connolly (executed after Easter Rising 1916).

- Joined the Anarchical Society (propagating anti-imperialist methods).

- Worked with Indian Students’ Association in Dublin (published pamphlets against racism & British atrocities in South Africa).

Key Influences on Giri

- Labour Rights: Deep commitment to trade unions and worker emancipation in India later.

- Nationalism: Irish experience gave him “complete sense of identity with the Irish cause” → parallels with India’s struggle.

- Revolutionary Inspiration: Inspired by Easter Rising (1916), despite suppression by British.

- Personal Resolve: After seeing Irish sacrifices, resolved to return to India and work for independence.

Political Repercussions

- Marked as a political radical by British authorities.

- Closely watched, deported back to India in 1917.

- Continued activism in India:

- Organised transport workers’ unions.

- Advocated labour rights + independence.

- Eventually became India’s President.

Indo-Irish Parallels

- Common struggle: Both nations under British imperialism.

- Labour movements: Key element in both nationalist struggles.

- Cross-learning: Indians drew from Irish revolutionary zeal; Irish saw India’s movement as sister-struggle.

- Shared leaders: Gandhi–South Africa (labour, non-violence) vs Connolly–Ireland (labour, armed resistance).

Broader Analysis

- Intellectual exchange: Globalisation of anti-colonial ideas even before independence.

- Labour as nationalism’s ally: National freedom tied to worker emancipation.

- Diaspora role: Students abroad became bridges for transnational solidarity.

- India’s labour politics: Shaped by this experience → Giri’s presidency symbolised merging of workers’ rights + democratic politics.

Contemporary Relevance

- Highlights importance of global solidarity in anti-colonial struggles.

- Lessons for today:

- Transnational unity against oppression (climate justice, workers’ rights).

- Role of student/youth movements in shaping politics.

- Reminder: Political empowerment must include economic emancipation of the working class (Giri’s lifelong message).