Content

- Equalising primary food consumption in India

- India needs more focus to reach SDG 3, a crucial goal

- Holistic approach

Equalising primary food consumption in India

Why in News?

- NSS Household Consumption Survey (2024) released after more than a decade enabled new poverty estimates.

- World Bank (April 2025) report (“Poverty and Equity Brief: India”) found extreme poverty fell from 16.2% in 2011–12 to 2.3% in 2022–23.

- Contrarian estimates by economists Pulapre Balakrishnan & Aman Raj (2025) argue food deprivation remains high when measured via a “thali consumption metric”.

Relevance

- GS2 (Governance): Food Security, PDS reforms, NFSA 2013.

- GS3 (Economy & Agriculture): Poverty measurement, subsidy efficiency, nutritional security.

- GS3 (Social Justice): Hidden hunger, inequality in consumption, welfare targeting.

Practice Question

Q. “India’s poverty estimates show sharp decline, but nutritional deprivation persists.” Critically evaluate the effectiveness of the Public Distribution System in addressing hidden hunger.(250 Words)

Basics

Poverty Measurement Approaches

- Conventional (India’s historic method): calorie-based minimum income thresholds.

- World Bank global metric: $2.15/day (PPP) for extreme poverty.

- Alternative (Thali Index): number of thalis affordable daily → reflects balanced diet, nourishment, and actual food expenditure.

Public Distribution System (PDS)

- Provides subsidised cereals (mainly rice & wheat) + free food in many states.

- Goal: Ensure food security under NFSA, 2013.

- Criticism: Inefficient targeting and misallocation of subsidies, often benefiting the non-poor.

Overview

Key Insights from Thali-Based Poverty Metric

- Cost of one thali: ₹30 (Crisil estimate, 2023).

- Standard: 2 thalis/day/person = minimum acceptable food consumption.

- Findings from HCES 2024:

- 50% rural and 20% urban population cannot afford 2 thalis/day.

- After including PDS subsidies: deprivation reduces to 40% rural and 10% urban → still significant, esp. rural.

- Explanation: Households spend on rent, health, education, etc. → food becomes residual expenditure, unlike assumption in official poverty lines.

PDS Effectiveness and Inefficiency

- Rural India:

- Even richer fractiles (90–95%) receive almost the same subsidy as the poorest (0–5%).

- PDS not progressive → mis-targeted.

- Urban India:

- Subsidies more progressive but 80% still benefit, even if food-secure.

- Cereal consumption equalised across classes, showing PDS success in staples but limits in addressing nutrition gaps.

Policy Proposal by Authors

- Restructure PDS Subsidies

- Cut cereal entitlements for the upper fractiles.

- Rationalise allocations to match actual need → reduce fiscal burden & FCI stocking costs.

- Expand Subsidy to Pulses

- Pulses are costly & main protein source for poor.

- Current pulse intake of poorest (0–5%) = half that of richest (95–100%).

- Expanding PDS to pulses can equalise primary nutrition across population.

- Compact, Need-Based PDS

- Focus subsidies only on those below 2 thali/day standard.

- Free up resources for health, education, infrastructure.

Broader Implications

- For Governance & Policy

- Reveals disconnect between official poverty estimates and actual nutritional deprivation.

- Challenges India’s “poverty-free” narrative, showing hidden hunger.

- For Public Finance

- Current subsidies spread thin across 80 crore beneficiaries.

- Rationalisation could reduce food subsidy bill (~₹2 lakh crore annually) and improve fiscal space.

- For Nutrition & SDGs

- India’s “triple burden” (undernutrition, micronutrient deficiency, obesity) demands a shift from calorie-security to nutrition-security.

- Pulse-centric PDS aligns with SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and improves protein adequacy.

- For Equity & Justice

- Current design subsidises even the non-poor → regressive.

- A progressive, nutrition-focused PDS would equalise core food intake, reducing hidden inequality.

Way Forward

- Move from cereal-dominated PDS → diversified nutrition basket (pulses, millets, oil).

- Improve targeting using real-time household consumption data.

- Integrate with Poshan Abhiyaan & ICDS to link PDS with maternal-child nutrition.

- Regularly publish HCES surveys for timely recalibration of subsidies.

- Consider direct benefit transfers (DBTs) for better efficiency in urban areas, while maintaining physical PDS in rural/tribal belts.

India needs more focus to reach SDG 3, a crucial goal

Why in News?

- India’s SDG Index Rank 2025: India ranked 99 out of 167 countries, its best-ever position, improving from 109 in 2024.

- Progress in basic services & infrastructure, but lagging in health and nutrition (SDG 3), especially in rural/tribal areas.

- Editorial focuses on SDG 3 (Health & Well-being) and strategies needed for India to get back on track.

Relevance

- GS2 (Governance & Social Justice): Health policy, Ayushman Bharat, primary healthcare reforms.

- GS3 (Economy): OOPE, health financing, insurance coverage.

- GS2/GS3 (International): India’s role in achieving global SDGs by 2030.

Practice Question :

Q. Despite significant progress in health infrastructure, India lags in SDG 3 targets. Discuss the structural barriers and suggest a three-pronged approach to achieve “health for all” by 2030.(250 Words)

Basics

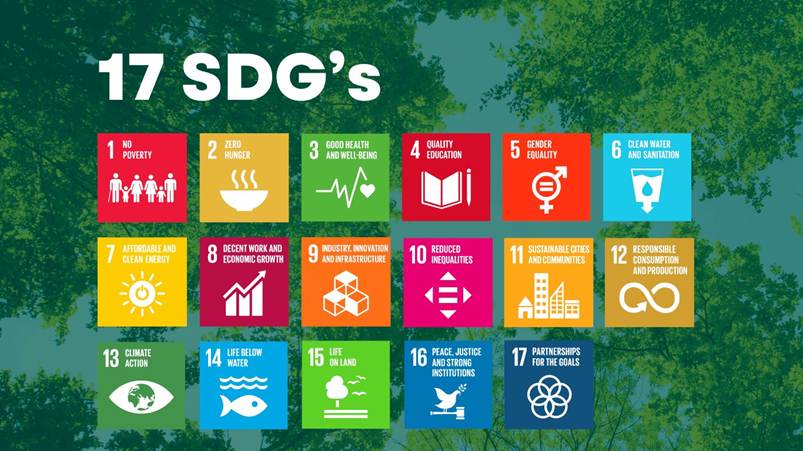

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- Adopted by UN in 2015, 17 goals, 169 targets, deadline 2030.

- India’s monitoring: NITI Aayog’s SDG India Index.

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- Goal: “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”

- Key targets for India:

- Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR): 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030.

- Under-five mortality rate: ≤25 per 1,000 live births.

- Life expectancy: 73.6 years.

- Out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE): reduce to 7.83% of household consumption.

- Universal immunisation: 100%.

Overview

India’s Performance Gaps in SDG 3

- Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR): 97 (target 70).

- Under-5 Mortality: 32 per 1,000 live births (target 25).

- Life Expectancy: 70 years (below 73.6 target).

- OOPE: 13% of consumption (target 7.8%).

- Immunisation: 93% (short of 100%).

Causes of Gaps

- Economic barriers – affordability, OOPE burden.

- Infrastructure gaps – weak primary health care in rural/tribal regions.

- Non-economic factors – malnutrition, poor sanitation, lifestyle diseases.

- Cultural barriers & stigma – mental health, reproductive health, taboos.

Proposed Three-Pronged Approach

- Universal Health Insurance

- Ensures equity in access & reduces catastrophic expenditure.

- Supported by World Bank studies on positive global outcomes.

- Strengthening Primary Health Care

- Functional PHCs with coordination across primary, secondary, tertiary levels.

- WHO (2022) highlights role of strong primary systems in early detection & lower costs.

- Digital tools (telemedicine, e-health records) can bridge rural gaps.

- Example: Lancet Digital Health Commission → digital platforms improved maternal care, vaccination in LMICs.

- School-based Health Education (Prevention)

- Focus on nutrition, hygiene, reproductive health, mental health, road safety.

- Habits formed in childhood sustain into adulthood.

- Global precedents:

- Finland (1970s): health curriculum lowered cardiovascular mortality.

- Japan: compulsory health education → improved hygiene, longer life expectancy.

- Long-term impact: Lower MMR, under-5 mortality; higher life expectancy & immunisation.

Broader Implications

- Governance & Policy: Need for integrated strategy → universal health coverage + school curricula + preventive care.

- Public Health: Tackling India’s “double burden” → unfinished agenda of maternal/child health + rising NCDs/obesity.

- Economy: Reduced OOPE frees household budgets, boosts productivity.

- Global Alignment: India’s progress critical to achieving global SDGs (only 17% on track globally).

- Viksit Bharat 2047: Long-term vision requires embedding health education + robust systems, beyond 2030 deadlines.

Way Forward

- Expand AB-PMJAY to ensure universal health coverage.

- Invest in Saksham Anganwadis + Ayushman Bharat Health & Wellness Centres.

- Integrate Digital India with Health Stack for e-records, telemedicine.

- Make school health education compulsory (nutrition, mental health, reproductive health).

- Promote community health literacy & engage parents in health curricula.

- Shift focus from curative → preventive health for cost-effective outcomes.

Holistic approach

Why in News?

- Supreme Court suggestion: prosecuting farmers for stubble burning to curb winter air pollution.

- Context: October–November smog in Delhi-NCR, caused by stubble burning + vehicular emissions + industrial pollution + meteorological trapping.

- Challenge: Existing mechanisms like the Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) remain ineffective due to political pressures, weak enforcement, and flawed incentives.

Relevance

- GS3 (Environment): Air pollution, sustainable agriculture, climate impacts.

- GS2 (Governance): Federalism, CAQM’s role, judicial vs executive balance.

- GS3 (Economy): Cost of pollution on GDP, farm economics.

- GS3 (Science & Tech): Bio-decomposers, mechanisation, agri-tech innovations.

Practice Question :

Q. Stubble burning is less a farmer’s choice and more a symptom of structural agricultural economics. Evaluate the effectiveness of current institutional mechanisms and suggest a multi-pronged strategy for long-term resolution.(250 Words)

Basics

What is Stubble Burning?

- Practice of burning leftover paddy straw after harvest to clear fields quickly for rabi sowing (wheat).

- Common in Punjab, Haryana, Western UP.

Why Farmers Burn Stubble?

- Short sowing window (due to delayed paddy harvest).

- High cost of alternatives (machinery, manual removal).

- Debt burden and economic compulsions.

- Lack of market for crop residue.

Impacts of Stubble Burning

- Contributes 20–30% of Delhi-NCR winter PM2.5 levels.

- Severe health costs (respiratory diseases, reduced productivity).

- Soil degradation → loss of nutrients & soil microbes.

- Climate impact: releases CO₂, CH₄, N₂O (greenhouse gases).

Overview

Institutional Mechanism: CAQM

- Established in 2020 as a statutory body for air quality management across NCR and adjoining states.

- Powers: coordinate inter-state actions, issue binding directions.

- Weaknesses:

- Political interference (example: postponement of “end-of-life vehicle” ban).

- Opaque reporting (Punjab’s under-reporting of farm fires).

- Inaction on enforcement & farmer incentives.

Current Problem

- Judiciary floating “jail farmers” proposal → reflects failure of executive/CAQM to offer structural solutions.

- Blaming farmers alone ignores systemic agricultural economics.

Multi-pronged Strategy Needed

1. Economic Incentives

- Direct subsidy for stubble management machinery (Happy Seeder, Super Straw Management System).

- MSP diversification: Encourage less water-intensive crops → millets, pulses.

- Crop residue monetisation: promote biomass power plants, ethanol production, cardboard industry.

2. Legal & Regulatory Measures

- Strict enforcement against industrial and vehicular polluters (parallel contributors).

- Transparent satellite-based monitoring of farm fires with accountability on states.

- Penalties on state governments for non-compliance, not just farmers.

3. Technological & Ecological Solutions

- Pusa bio-decomposer (IARI innovation) to decompose stubble in-situ.

- Mechanisation support through FPOs and custom hiring centres.

- Agroforestry & crop diversification to reduce residue burden.

4. Governance Reforms

- Empower CAQM with real independence from political pressure.

- Time-bound transparent reporting of stubble fires.

- Participatory approach: farmers’ unions, state governments, local panchayats included in decision-making.

Broader Implications

- Health & Economy: India loses ~1.36% of GDP annually due to air pollution (World Bank, 2022).

- Agriculture & Climate Nexus: Water-guzzling paddy + stubble burning → both environmental & climate challenges.

- Federalism: Pollution is transboundary; requires cooperative federalism.

- Judiciary-Executive balance: Over-reliance on judicial nudges shows weak policy enforcement.

Way Forward

- Shift approach from “punitive action on farmers” → “structural reforms & incentives”.

- Reorient subsidies & MSP to encourage sustainable cropping.

- Scale-up bio-decomposer + biomass economy.

- Strengthen CAQM’s independence with parliamentary oversight.

- Integrate air pollution control into climate change and public health policies.