Why in News ?

- New peer-reviewed research (published in Nature Climate Change, Oct 2024) shows the Southern Ocean has absorbed more carbon dioxide since the early 2000s, contradicting long-standing climate model projections.

- Highlights limits of climate models, importance of observations, and risks of abrupt future shifts in the global carbon cycle.

Relevance

GS III – Environment & Climate Change

- Global carbon cycle.

- Oceanic carbon sinks.

- Climate feedback mechanisms.

- Non-linear climate responses.

GS I – Geography (Physical)

- Ocean circulation systems.

- Stratification, upwelling, westerlies.

- Southern Ocean’s role in global climate regulation.

Why the Southern Ocean Matters?

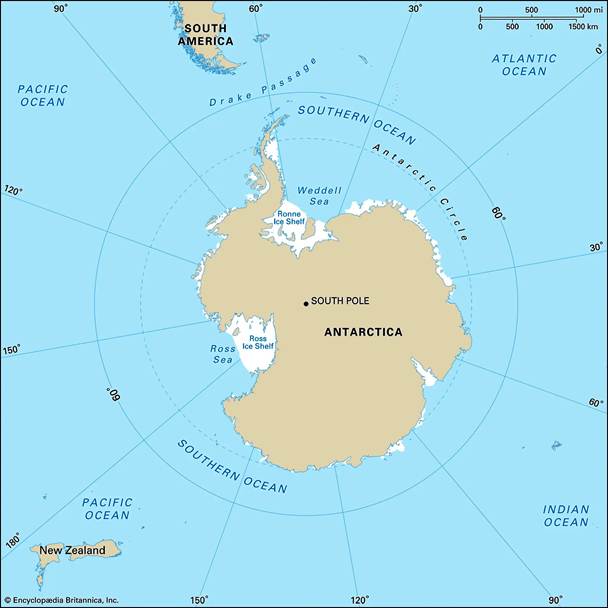

- Covers ~25–30% of global ocean area.

- Absorbs ~40% of oceanic uptake of anthropogenic CO₂.

- Acts as a global climate regulator by:

- Absorbing excess heat.

- Functioning as a major carbon sink.

Inference: Small physical changes here have disproportionately large global climate impacts.

How the Southern Ocean Carbon Sink Works ?

- Cold, relatively fresh surface waters form a “lid”.

- Beneath lies warmer, saltier, carbon-rich deep water.

- Strong stratification limits vertical mixing → carbon remains trapped below surface → less CO₂ escapes to atmosphere.

What Climate Models Predicted (Pre-2020 Consensus) ?

- Rising greenhouse gases → stronger & poleward-shifting westerly winds.

- This would intensify Southern Ocean Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC).

- Result:

- More upwelling of deep, carbon-rich water.

- Increased CO₂ outgassing.

- Weakening of Southern Ocean carbon sink.

What Observations Actually Show (The “Anomaly”)?

Confirmed Model Predictions

- Circumpolar Deep Water has risen ~40 metres since the 1990s.

- Subsurface CO₂ pressure increased by ~10 microatmospheres.

- Stronger upwelling is real.

Unexpected Outcome

- Despite this, net CO₂ absorption increased, not decreased.

- Southern Ocean remained a strong carbon sink.

What Models Missed: The Key Mechanism?

Freshwater-Driven Stratification

- Increased:

- Antarctic ice melt.

- Precipitation.

- Result:

- Fresher (lighter) surface waters.

- Enhanced stratification.

- Effect:

- Carbon-rich waters trapped 100–200 m below surface.

- Prevented contact with atmosphere → no CO₂ release.

Conclusion: A surface freshwater “mask” temporarily counteracted deep upwelling effects.

Why This Is Temporary (High-Risk Insight)?

- Observations since early 2010s show:

- Stratified layer thinning.

- Surface salinity rising again in parts of the Southern Ocean.

- Strong winds can:

- Penetrate weakened stratification.

- Mix deep, carbon-rich waters upward.

- Result:

- Delayed but abrupt weakening of the carbon sink possible.

- Potential for sudden CO₂ release, not gradual.

Why Models Struggle Here (Scientific Limits)?

- Competing processes:

- Upwelling (vertical transport).

- Stratification (vertical blockage).

- Governed by multi-scale physics:

- Eddies (few km wide).

- Ice-shelf cavities (tens–hundreds of km).

- Sparse year-round observations in Southern Ocean.

Inference: Model uncertainty ≠ model failure; reflects data and scale constraints.

Broader Climate Governance Implications

- Reinforces need for:

- Continuous ocean observations (floats, moorings, satellites).

- Stronger investment in Southern Ocean monitoring.

- Warns policymakers against:

- Assuming long-term ocean buffering.

- Raises stakes for:

- Carbon budget calculations.

- Net-zero timelines.

- Climate tipping point assessments.

Conclusion

- Climate systems can show non-linear responses.

- Temporary resilience can mask deeper vulnerabilities.

- Policy must integrate:

- Models (future risks).

- Observations (current reality).

- Southern Ocean exemplifies “delayed feedback risk” in climate change.