Contents

- SHOULD THE GOVERNMENT EXIT NAVARATNA COMPANIES?

- EXPLAINED: HOW SECTION 144 CrPC WORKS?

SHOULD THE GOVERNMENT EXIT NAVARATNA COMPANIES?

Why in news?

Last month, the Cabinet approved sale of the government’s stake in Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited, a Navratna public sector company with oil refining and marketing operations.

Backgrounder

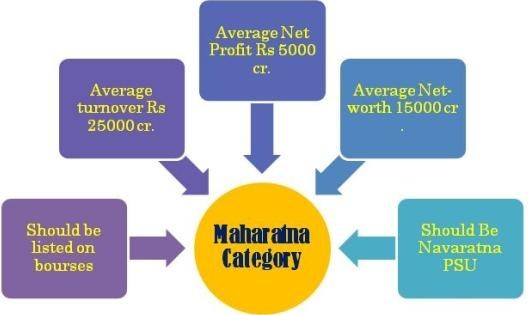

The Public Sector Enterprises are run by the Government under the Department of Public Enterprises of Ministry of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises. The government grants the status of Navratna, Miniratna and Maharatna to Central Public Sector Enterprises based upon the profit made by these CPSEs.

List of Maharatna Companies in India

1. Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited

2. Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited

3. Coal India Limited

4. GAIL (India) Limited

5. Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited

6. Indian Oil Corporation Limited

7. NTPC Limited

8. Oil & Natural Gas Corporation Limited

9. Power Grid Corporation of India Limited

10. Steel Authority of India Limited

The Navratna companies:

The company must have ‘Miniratna Category – I‘ status along with a Schedule ‘A’ listing.

Along with the above, it should also have a composite score of 60 or above out of possible 100 marks in the 6 selected performance parameters:-

- Net Profit to Net Worth (Maximum: 25)

- Manpower cost to cost of production or services (Maximum: 15)

- Gross margin as capital employed (Maximum: 15)

- Gross profit as Turnover (Maximum: 15)

- Earnings per Share (Maximum: 10)

- Inter-Sectoral comparison based on Net profit to net worth (Maximum: 20)

- There are 14 Navratna CPSEs in the country

List of Navratna Companies in India

1.Bharat Electronics Limited

2. Container Corporation of India Limited

3. Engineers India Limited

4. Hindustan Aeronautics Limited

5. Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Limited

6. National Aluminium Company Limited

7. NBCC (India) Limited

8. NMDC Limited

9. NLC India Limited

10. Oil India Limited

11. Power Finance Corporation Limited

12. Rashtriya Ispat Nigam Limited

13. Rural Electrification Corporation Limited

14. Shipping Corporation of India Limited

Disinvestment and Policies

- Disinvestment is the process of reducing the share of government in public sector undertakings (PSUs).

- It is the sale of shares of the government in these companies to financial institutions, employees or the public at large.

- In disinvestment, also called divestment, there is no change in the management of PSUs from the public to private hands as the government still holds majority equity (51 percent).

- Even when the government’s share falls below 51 percent, the rest of the equity may be sold in such a way that no one institution or individual holds enough stake to take control of the management.

- Disinvestment is primarily a money-raising exercise.

- The proceeds of disinvestment are treated as non-debt creating capital receipts. Though the government can technically hold a stake less than 51 percent and still be the largest shareholder in PSUs, it was not done on a large scale. This is because a PSU ceases to be a public sector company post such exercise.

Disinvestment of a majority stake in PSUs:

- Strategic sale: it is the sale of a substantial portion of government shareholding, 50 percent or higher, in a PSU, along with the transfer of management control.

- Privatization: it’s a type of strategic sale in which the government divests its entire shareholding, along with the transfer of management control, to a private entity.

In 1998, the government has categorized the PSUs into two broad categories:

- Strategic PSUs: include arms and ammunition, railways, and nuclear energy. No disinvestment from these PSUs.

- Non-strategic PSUs: all other PSUs not included in the above category. Disinvestment in these PSUs to take place in a phased manner. To oversee the process of disinvestment, a separate Department of Disinvestment was created under the Ministry of Finance (in 2004).

Here in this particular editorial, T.T. Ram Mohan and C.P. Chandrasekhar discuss the implications of BPCL’s stake sale

Points from this discussion:

- During Vajpayee government, the original understanding was that you go in for partial disinvestment to public sector equity with two purposes, among many.

- One was it would allow you to mobilise a certain amount of resources which can be put into some kind of a fund which could be used to modernise, renovate or make viable public sector firms which still have the possibility of being profitable despite being loss-making. This could also be used to put money into firms that were so loss-making that it is best to shut them down, by paying off retrenchment funds to workers and cleaning the books.

- The other was that having private equity holding in public firms brings in a certain degree of monitoring and discipline of managers in the public sector that comes from outside the government. We have clearly shifted from both of these.

- The CEA recently argued that the private sector does a far better job of taking savings in the economy and making sure that they are ploughed back productively. One of the long-standing problems of India’s public sector has been about bureaucratic and political interference and rent-seeking.

- We just have to look at the civil aviation sector where we brought in the private sector in a big way. You have to look at what “competition” has done in the telecom sector. And we know that survival in these sectors for a number of firms was essentially because they were bankrolled by public sector banks.

- Even in post-liberalisation India, a number of studies show a trend towards convergence in performance between PSUs and private enterprises.

- One of the reasons people tend to believe that the private sector is more efficient is because there’s something called a survivorship bias in the data. When a public sector enterprise makes losses, it continues to exist.

- Whereas, if a private sector enterprise makes losses for a long time, it sort of exits the database. So, people will look at public and private sector banks and say private sector banks are doing much better, but they will ignore the many private sector banks that failed and had to be merged with other entities.

- The problem in comparing the two is that only the survivors of the private sector are left standing and you say they are doing marvellously.

- One of the arguments being made about BPCL is that if the government sells it now when it is doing well, then it stands to realise a very good price. But if and when private competition comes into distribution of oil, then BPCL surely will not do well and the government wouldn’t realise the same price. That is just pessimistic thinking

- In Parliament, when asked about its disinvestment policy, the government said this month that it is not driven by profit or loss but decided on the basis of ‘national security, sovereign functions, market imperfections and public purpose.’

Way forward:

- The Disinvestment Commission under G.V. Ramakrishna was very clear that privatisation should be for strengthening the public sector. So they ruled out privatisation of core industries and highly profitable PSUs, and they also said the proceeds should be used for restructuring other PSUs or spending on rural infrastructure. The receipts should not be used for the government’s revenue expenditure.

EXPLAINED: HOW SECTION 144 CrPC WORKS?

Why in news?

Recently various state governments sought to tamp down on the demonstrations by issuing prohibitory orders under Section 144 of the Code Of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973.

What is Section 144?

- Section 144 CrPC, a law retained from the colonial era, empowers a district magistrate, a sub-divisional magistrate or any other executive magistrate specially empowered by the state government in this behalf to issue orders to prevent and address urgent cases of apprehended danger or nuisance.

- The magistrate has to pass a written order which may be directed against a particular individual, or to persons residing in a particular place or area, or to the public generally when frequenting or visiting a particular place or area.

- In emergency cases, the magistrate can pass these orders without prior notice to the individual against whom the order is directed.

What powers does the administration have under the provision?

The magistrate can direct any person to abstain from a certain act or to take a certain order with respect to certain property in his possession or under his management. This usually includes restrictions on movement, carrying arms and from assembling unlawfully.

It is generally believed that assembly of three or more people is prohibited under Section 144.

However, it can be used to restrict even a single individual.

However, no order passed under Section 144 can remain in force for more than two months from the date of the order, unless the state government considers it necessary. Even then, the total period cannot extend to more than six months.

Why is the use of power under Section 144 criticised so often?

The criticism is that definition given in the section is too vague in nature.

The immediate remedy against such an order is a revision application to the magistrate himself (conflict of interest).

An aggrieved individual can approach the High Court by filing a writ petition if his fundamental rights are at stake.

How have courts ruled on Section 144?

- In Babulal Parate vs State of Maharashtra and Others (1961), a Bench of the Supreme Court refused to strike down the law, saying it is “not correct to say that the remedy of a person aggrieved by an order under the section was illusory”.

- It was challenged again by Dr Ram Manohar Lohiya in 1967 and was once again rejected, with the court saying “no democracy can exist if ‘public order’ is freely allowed to be disturbed by a section of the citizens”.

- In another challenge in 1970 (Madhu Limaye vs Sub-Divisional Magistrate), a seven-judge Bench headed by then CJI M Hidayatullah, It ruled that the power under Section 144 is not an ordinary power flowing from administration but a power used in a judicial manner and which can stand further judicial scrutiny”.

- The court, however, upheld the constitutionality of the law.

- It ruled that the restrictions imposed through Section 144 cannot be held to be violative of the right to freedom of speech and expression, which is a fundamental right because it falls under the “reasonable restrictions”.

In 2012, the Supreme Court came down heavily on the government for imposing Section 144 against a sleeping crowd in Ramlila Maidan.

“Such a provision can be used only in grave circumstances for maintenance of public peace. The efficacy of the provision is to prevent some harmful occurrence immediately. Therefore, the emergency must be sudden and the consequences sufficiently grave,”.

Does Section 144 provide for communications blockades too?

The rules for suspending telecommunication services, which include voice, mobile internet, SMS, landline, fixed broadband, etc, are the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules, 2017.

These Rules derive their powers from the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885, Section 5(2) of which talks about interception of messages in the “interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India”.

However, shutdowns in India are not always under the rules laid down, which come with safeguards and procedures. Section 144 CrPC has often been used to clamp down on telecommunication services and order Internet shutdowns.