Contents

- Putting the SAGAR vision to the test

- Explained: Why are oil futures in negative terrain?

- The key strategy is fiscal empowerment of States

- A change in migrant policy

- Futures shock: On oil price fall below $0

PUTTING THE SAGAR VISION TO THE TEST

Focus: GS-II International Relations

What is SAGAR?

- In March 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited three small but significant Indian Ocean island states — Seychelles, Mauritius, and Sri Lanka. During this tour, he unveiled India’s strategic vision for the Indian Ocean: Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR).

- SAGAR seeks to differentiate India’s leadership from the modus operandi of other regionally active major powers and to reassure littoral states as India’s maritime influence grows.

- India’s SAGAR vision is intended to be “consultative, democratic and equitable”.

- India’s recent admission as observer to the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) will put this vision to the test.

- Following a request from New Delhi, the IOC granted observer status to India on March 6 at the Commission’s 34th Council of Ministers.

IOC

Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) is an intergovernmental organisation comprising five small-island states in the Western Indian Ocean: the Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Réunion (a French department), and Seychelles.

Indian Ocean Commission member states

The IOC works on four pillars which have been adopted in 2005 by the Summit of Heads of States:

- Political and diplomatic cooperation,

- Economic and commercial cooperation

- Sustainable development in a globalisation context, cooperation in the field of agriculture, maritime fishing, and the conservation of resources and ecosystems

- Strengthening of the regional cultural identity, cooperation in cultural, scientific, technical, educational and judicial fields.

Significance of IOC

- Over the years, the IOC has emerged as an active and trusted regional actor, working in and for the Western Indian Ocean and implementing a range of projects.

- More recently, the IOC has demonstrated leadership in the maritime security domain. Since maritime security is a prominent feature of India’s relations with Indian Ocean littoral states, India’s interest in the IOC should be understood in this context.

- However, India has preferred to engage bilaterally with smaller states in the region.

- What India will not find in the IOC is a cluster of small states seeking a ‘big brother’ partnership.

- The IOC has its own regional agenda, and has made impressive headway in the design and implementation of a regional maritime security architecture in the Western Indian Ocean.

- In 2012, the IOC was one of the four regional organisations to launch the MASE Programme — the European Union-funded programme to promote Maritime Security in Eastern and Southern Africa and Indian Ocean.

- Under MASE, the IOC has established a mechanism for surveillance and control of the Western Indian Ocean with two regional centres.

- The Regional Maritime Information Fusion Center (RMIFC), based in Madagascar, is designed to deepen maritime domain awareness by monitoring maritime activities and promoting information sharing and exchange.

- The Regional Coordination Operations Centre (RCOC), based in Seychelles, will eventually facilitate joint or jointly coordinated interventions at sea based on information gathered through the RMIFC.

- These centres are a response to the limitations that the states in the region face in policing and patrolling their often-enormous Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs).

- The IOC has also wielded a disproportionate degree of convening power. In 2018 and 2019, it served as Chair of the Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia (CGPCS).

- The IOC’s achievements offer an opportunity for India to learn, and also to support. The IOC style of ‘bottom-up regionalism’ has produced a sub-regional view and definition of maritime security problems and local ownership of pathways towards workable solutions.

- Its regional maritime security architecture is viewed locally as the most effective and sustainable framework to improve maritime control and surveillance and allow littoral States to shape their own destiny.

- Moreover, with proper regional coordination, local successes at curbing maritime threats will have broader security dividends for the Indian Ocean space.

How can India contribute?

- The IOC’s maritime security activities have a strong foundation, but they require support and buy-in from additional regional actors.

- India has already signalled a strong interest in the work of the IOC through its request to be admitted as an observer.

- Nearly all littoral states in the Western Indian Ocean need assistance in developing their maritime domain awareness and in building capacity to patrol their EEZs.

- All would benefit from national information fusion centres that can link to those of the wider region.

- With its observer status, India will be called upon to extend its expertise to the region, put its satellite imagery to the service of the RMIFC, and establish links with its own Information Fusion Centre.

- As a major stakeholder in the Indian Ocean with maritime security high on the agenda, India will continue to pursue its interests and tackle maritime security challenges at the macro level in the region.

- However, as an observer of the IOC, a specific, parallel opportunity to embrace bottom-up regionalism presents itself.

- There are those in the Western Indian Ocean who are closely watching how India’s “consultative, democratic and equitable” leadership will take shape.

EXPLAINED: WHY ARE OIL FUTURES IN NEGATIVE TERRAIN?

Focus: GS-III Indian Economy, GS-II International Relations

Story so far

Prices of West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the American benchmark for crude oil, fell to less than zero in Monday’s trade. The price of a barrel of WTI fell to minus, yes, that’s right, minus $37.63 a barrel. What this means is that sellers have to pay buyers to get rid of their crude! This is unprecedented in the oil market, even accounting for its notoriety for being volatile.

Why did prices fall like this?

- The reason was straightforward: Too much supply and too little demand (see Chart 1). To a great extent, oil markets, globally and more so in the US, are facing an enormous glut.

- Historically, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, which is the largest exporter of crude oil in the world (single-handedly exporting 10% of the global demand), used to work as a cartel and fix prices in a favourable band. It could bring down prices by increasing oil production and raise prices by cutting production.

- In the recent past, the OPEC has been working with Russia, as OPEC+, to fix the global prices and supply.

- The global oil pricing is by no stretch an example of a well-functioning competitive market. In fact, its seamless operations crucially depend on oil exporters acting in consort.

- The May contracts for WTI, the American crude oil variant, were due to expire on Tuesday, April 21. As the deadline approached, prices started plummeting. This was for two broad reasons.

- By Monday 20th April, there were many oil producers who wanted to get rid of their oil even at unbelievably low prices rather than choose the other option — shutting production, which would have been costlier to restart when compared to the marginal loss on May sales.

- From the consumer side, that is those holding these contracts, it was an equally big headache. Contract holders wanted to get wriggle out of the compulsion to buy more oil as they realised, quite late in hindsight, that there was no space to store the oil if they were to take the delivery.

- This desperation from both sides — buyers and sellers — to get rid of oil meant the WTI oil contract prices not only plummeted to zero but also went deep into the negative territory.

So, why can’t traders buy cheap oil now and store them for release in future when demand and prices rise?

That’s exactly what traders are now doing. Such a practice became famous during Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 when a trader took massive positions at cheap prices ahead of the invasion and sold them when prices rose after the invasion. Oil was stored in tankers floating on the sea and unloaded at considerably higher prices.

But the problem is that such floating storage is also fast running out of capacity; land storage in America is already overflowing. This would explain why oil prices are falling without support.

How will this impact India?

The Indian crude oil basket does not comprise WTI — it only has Brent and oil from some of the Gulf countries — so there is no direct impact. But oil is traded globally and weakness in WTI is mirrored in the falling prices of the Indian basket as well.

There are two ways in which this lower price can help India. If the government passes on the lower prices to consumers, then, whenever the economic recovery starts in India, individual consumption will be boosted. If, on the other hand, governments (both at the Centre and the states) decide to levy higher taxes on oil, it can boost government revenues.

THE KEY STRATEGY IS FISCAL EMPOWERMENT OF STATES

Focus: GS-II Governance

Need for relief

- It now appears that the lockdown will be lifted in stages and the recovery process will be prolonged.

- The country is literally placed in financing a war-like situation and the government will have to postpone the fiscal consolidation process for the present, loosen its purse strings and finance its deficits substantially through monetisation.

- This is also the time for the government to announce relaxation in the States’ fiscal deficit limit to make them effective participants in the struggle.

- It is also important for the States to realise the importance of health and prioritise spending on health-care services.

Significant Role of States

- Being closer to the people, the States have a much larger responsibility in fighting this war. Public health as well as public order are State subjects in the Constitution.

- In fact, some States were proactive in dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak by involving the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897, even before the Government of India declared a universal lockdown invoking the Disaster Management Act, 2005.

- The Centre under Entry 29 of the Concurrent List has the powers to set the rules of implementation which states, “Prevention of the extension from one State to another of infectious or contagious diseases or pests affecting men, animals or plants”.

- While Central intervention was done to enable, “consistency in the application and implementation of various measures across the country”, the actual implementation on the ground level will have to be done at the State level.

Focus on health and economy

- The pandemic has underlined the historical neglect of the health-care sector in the country. The total public expenditures of Centre and States works out to a mere 1.3% of GDP.

- The centrally sponsored scheme, the National Health Mission, is inadequately funded, micromanaged with grants given under more than 2,000 heads and poorly targeted.

- Besides protecting lives and livelihoods, States will have to initiate and facilitate economic revival, and that too would require substantial additional spending.

- Hand holding small and medium enterprises which have completely ceased production, providing relief to farmers who have lost their perishable crops and preparing them for sowing in the kharif season are other tasks that require spending.

Extensive revenue losses

- In the lockdown period, there has virtually been no economic activity and they have not been able to generate any revenue from State excise duty, stamp duties and registration fees, motor vehicles tax or sales tax on high speed diesel and motor spirit.

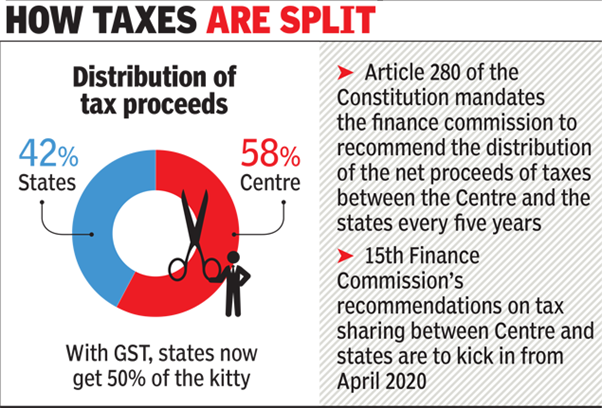

- The revenue from Goods and Services Tax is stagnant and compensation on time for the loss of revenue has not been forthcoming.

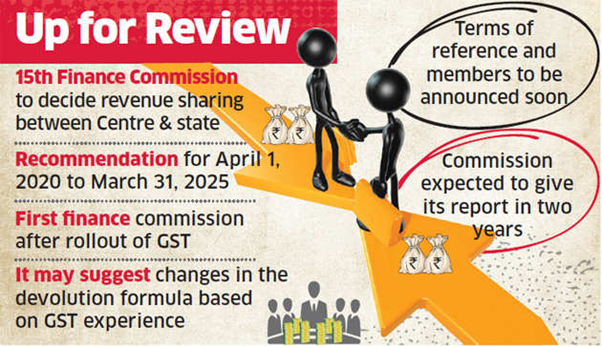

- The position regarding tax devolution from the Centre is even more precarious.

- To begin with, the tax devolution in the Union Budget estimate is lower than the Commission’s estimate.

Conclusion, Way Forward

- The war on COVID-19 can be effectively won only when the States are armed with enough resources to meet the crisis.

- Their borrowing space too is limited by the fiscal responsibility and budget management limit of 3% of Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP).

- The announcement by the Reserve Bank of India on the increase in the limit of ways and means advances by 60% of the levels prescribed in March 31 could help States to plan their borrowing better; but that is too little to provide much relief.

- herefore, it is important for the Central government to provide additional borrowing space by 2% of GSDP from the prevailing 3% of GSDP.

- This is the time to fiscally empower States to wage the COVID-19 war and trust them to spend on protecting lives, livelihoods and initiate an economic recovery.

A CHANGE IN MIGRANT POLICY

Focus: GS-II Social Justice

Why in news?

The condition of seasonal migrants has emerged as no less an important issue than the novel coronavirus itself.

The COVID-19 crisis has, for the first time, brought migration to the centre stage of public health and disaster response in India.

Why migrants occupy centre stage?

The context of state action that migrants have drawn sharp attention in debates over public health and political economy for at least five reasons.

- First, the numbers involved are very high: data suggest that there are approximately 2 million daily wage workers.

- Second, India’s economy, particularly of the growth centres, depends on the services of migrant workers. Sectors such as construction, garment manufacturing, mining, and agriculture would come to a standstill without them.

- Third, the return of migrants brings to the source States an economic shock as there are no compensatory sources of livelihood.

- Fourth, in the case of epidemics, the exodus of seasonal migrants creates apprehensions about the spread of the disease and runs counterproductive to the very purpose of a lockdown. Daily-wage earners do not have the capacity to stay at a destination without work. Their families back home depend on their daily savings. A considerable number of workers live within the manufacturing units or at work sites. Any lockdown results in loss of their accommodation too.

- Fifth, the pathetic working and living conditions of migrants defy the very idea of decent work and general security. Slums and slum-like colonies are breeding grounds of ailments and communicable diseases.

Issues with Delivering relief packages

- Some amelioration may be in sight with the ₹1.70 lakh crore relief package announced by the Central government. However, despite the government’s good intentions, the package will not benefit seasonal migrants.

- Those migrants who are unable to return home and are not ration cardholders in the cities where they are stationed will not benefit from additional free food grains under the PDS. They cannot avail of increased MGNREGA wages until they go back home.

- As many seasonal migrants are landless or marginal farmers, they will not benefit from the grant to landholders.

- Neither will they get benefits under the Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Board because of low registration.

- Thus, this workforce will remain largely deprived of the benefits under the present package at their destination places.

- The State needs to think out of the box in delivering relief packages.

FUTURES SHOCK: ON OIL PRICE FALL BELOW $0

Focus: GS-III Indian Economy

Why in news?

- May futures for the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) U.S. crude plunged below zero to touch a historic low of -$40.32 a barrel.

- A perfect storm of a supply glut exacerbated in March by a price war that saw key producers Saudi Arabia and Russia ramp up output even as demand continued to contract on account of the COVID-19 outbreak sent prices into a steeper slide.

- The confinement measures instituted worldwide have resulted in a dramatic decline in transportation activity which will erase at least a decade of demand growth.

What can be done about it?

- With storage for crude — on land or offshore in supertankers — nearing capacity or becoming prohibitively expensive, oil producers are going to have little option but to curtail output.

- India has prudently been using the sharp fall in both crude prices and domestic demand to accelerate the build-up of its strategic reserve.

- While the sliding oil prices would help significantly pare India’s energy import bill, a protracted demand drought would end up hurting the government’s tax revenues severely, especially at a time when it badly needs every additional rupee it can garner

- Also, rock-bottom oil prices risk damaging the economies of producer countries including those in West Asia, hurting inward remittances.

- After the lockdown, the Centre ought to consider using this opportunity to cut retail fuel prices sharply by foregoing some excise revenue for a while in order to tease back momentum into the wider economy.