Content

- A Court ruling with no room for gender justice

- Reviving civic engagement in health governance

- Assuaging concerns

A Court ruling with no room for gender justice

Background of the Law

- Section 498-A, IPC (now Section 85, Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita)

- Enacted in 1983 to address cruelty by husband or relatives towards a wife.

- Punishment: Up to 3 years imprisonment + fine.

- Cruelty broadly defined to include:

- Dowry harassment.

- Driving the woman to suicide.

- Causing injury to life, limb, or health.

- Introduced after increasing dowry deaths and recognition that many cruelty cases end in suicide/murder.

- Works in conjunction with Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961 and other women-protection laws.

- Legislative intent: Rights-based protection in marriage, considering India’s socio-cultural context.

Relevance : GS 1(Society ) , GS 2(Social Justice , Governance)

Practice Question : The recent Supreme Court endorsement of a two-month “cool-off” period before arrest in Section 498-A IPC cases has reignited debates on judicial overreach, gender justice, and protection of victims of domestic violence. Critically analyse the judgment in light of constitutional principles, legislative intent, and the socio-legal realities of domestic violence in India.(250 Words)

The Recent Supreme Court Judgment

- Origin: Allahabad HC directions in an individual matrimonial dispute:

- No arrest or coercive action for two months (“cool-off” period) from complaint.

- Creation of Family Welfare Committees at district level to examine cases before action.

- SC’s Role:

- Endorsed HC’s blanket protection from arrest for two months.

- Did so without detailed socio-political analysis or hearing State govt fully.

- Effect:

- Even with strong evidence, police cannot arrest for 2 months.

- Risk to complainant’s safety.

- Encourages police inaction in domestic violence cases.

- Creates a precedent overriding legislative intent in criminal law.

Legal & Constitutional Concerns

- Separation of Powers:

- Parliament enacted law after social study & deliberation; SC effectively modifies operational enforcement.

- Judicial Overreach:

- Venturing into policy terrain without empirical basis.

- Goes against SC’s own principle (Sushil Kumar Sharma, 2005) that misuse is no ground to dilute a law.

- Equality Before Law:

- Selectively subjecting this criminal provision to more rigorous procedural barriers undermines uniformity of criminal law.

The ‘Misuse’ Narrative

- Past SC Observations:

- Preeti Gupta (2010) – non-bona fide cases.

- Sushil Kumar Sharma (2005) – “legal terrorism” remark.

- Arnesh Kumar (2014) – strict guidelines before arrest under 498-A.

- Empirical Reality:

- NCRB (2022): Conviction rate ~18%—higher than many other IPC crimes.

- Low conviction ≠ misuse; can be due to:

- Investigative lapses.

- Social/familial pressure on women to withdraw.

- Difficulty proving crimes in private/domestic spaces.

- High burden of proof (beyond reasonable doubt).

- NFHS-5: Massive under-reporting of violence against women.

- Rising case numbers linked to greater legal awareness, not necessarily false cases.

- Humsafar report: Misuse claims reflect institutional bias.

Social & Gender Justice Dimensions

- Structural Inequalities:

- Patriarchal family structures make women dependent and vulnerable.

- Domestic violence is often hidden, with minimal outside witnesses.

- Impact of Blanket Protection:

- Chilling effect on filing complaints.

- Increases physical & emotional risk for victims.

- Sends a signal that domestic violence is a “private matter” rather than a serious criminal offence.

- Victim Vulnerability:

- Immediate police action is crucial in many cases for safety & evidence preservation.

- Delay enables intimidation, destruction of evidence, and coercion into compromise.

Criminal Justice System Implications

- Operational Challenges:

- Police may deprioritise domestic cruelty cases.

- Creates confusion in enforcement due to differing treatment from other IPC offences.

- Uniformity Principle:

- Criminal law requires consistency; special procedural hurdles for one category may lead to fragmentation.

- Precedent Risk:

- Similar “cool-off” mechanisms may be sought in other crimes, weakening deterrence.

Balancing Misuse vs. Protection

- Potential for misuse exists in all laws, but safeguards already exist:

- Arrest guidelines (Arnesh Kumar).

- Judicial scrutiny at bail stage.

- Quashing under Section 482 CrPC for false cases.

- Better Solutions:

- Improve investigation quality.

- Sensitise police & judiciary.

- Fast-track genuine cases.

- Penalise proven false complaints without diluting protection for victims.

Key Takeaway

This judgment, while perhaps well-intentioned to prevent misuse, risks weakening legal protection for victims of domestic violence, creates procedural inequality in criminal law, and intrudes into policy space reserved for Parliament. The challenge is not in the existence of Section 498-A, but in ensuring its fair, efficient, and sensitive implementation.

Reviving civic engagement in health governance

Scheme Context & Comparative Perspective

- Makkalai Thedi Maruthuvam (Tamil Nadu, Aug 2021):

- Focus: Doorstep healthcare for NCD patients.

- Achievements: Reached 1.5 crore people (as per TN govt data, 2024).

- Gruha Arogya (Karnataka, Oct 2024; expanded June 2025):

- Focus: Home-based care, NCD screening, and follow-up services.

- Coverage: All districts from June 2025.

- Similar Models: Mohalla Clinics (Delhi), Arogya Mithra (Andhra Pradesh), Mobile Medical Units (Assam, Odisha).

- Global Parallel: Brazil’s Family Health Strategy – community-based teams delivering preventive and primary care at households.

- Similar schemes across States reflect proactive healthcare delivery, but they raise questions on citizen participation in governance—a critical component for accountability and rights-based healthcare.

Relevance : GS 2(Health , Governance)

Practice Question : Doorstep healthcare delivery schemes such as Tamil Nadu’s Makkalai Thedi Maruthuvam and Karnataka’s Gruha Arogya represent a shift towards proactive service provision. However, without active citizen participation in health governance, such initiatives risk remaining top-down and exclusionary. Examine the structural and mindset barriers to meaningful public engagement in India’s health governance, and suggest measures to overcome them.(250 Words)

Key Issues Identified

- Mindset Problem: Policymakers view people as beneficiaries rather than rights-holders or co-creators of health systems.

- Performance Metrics Bias: Success measured by targets met (beneficiaries reached) rather than process quality or community experience.

- Governance Capture: Decision spaces dominated by medical professionals trained in western biomedical models, with little exposure to public health administration.

- Structural Weakness in Engagement Platforms:

- Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committees (VHSNCs), Rogi Kalyan Samitis, Mahila Arogya Samitis often inactive or poorly functioning.

- Issues: infrequent meetings, poor fund utilisation, lack of inter-sectoral coordination, entrenched social hierarchies.

- Resistance Factors: Fear of increased workload, loss of elite control, and exposure to accountability pressures.

Implications

- Democratic Deficit in Health Governance: Without inclusive participation, health policy risks becoming top-down, technocratic, and inequitable.

- Erosion of Trust: Treating citizens as passive recipients reduces community trust and service uptake.

- Perpetuation of Health Inequities: Ignoring structural determinants (poverty, discrimination) while blaming individuals for poor health-seeking behaviour worsens marginalisation.

Citizen Engagement in Health Governance

- Why it matters:

- Strengthens accountability and transparency.

- Counters epistemic injustice (exclusion of lived experiences from policy).

- Enhances trust and uptake of services.

- Platforms in India:

- Rural: VHSNCs, Rogi Kalyan Samitis.

- Urban: Mahila Arogya Samitis, Ward Committees.

- Challenges:

- Non-functional or token committees in many areas.

- Ambiguous roles, poor intersectoral coordination, fund underutilisation.

- Social hierarchies excluding marginalised voices.

Structural & Mindset Barriers

- Dominance of biomedical, doctor-led administration → limited public health perspective.

- Promotions based on seniority, not public health expertise.

- “Beneficiary” terminology reduces citizens to passive aid receivers instead of rights-holders.

- Policymakers often focus on targets (beneficiaries covered) rather than process quality (participatory planning, inclusivity).

Lessons from Existing Frameworks

- NRHM (2005) & NHM: Institutionalised public engagement via VHSNCs and untied funds, but success uneven due to poor activation.

- Urban Civic Bodies: Ward Committees, NGO-led health committees show potential but face capacity and legitimacy gaps.

- Alternative Channels: Citizens resort to protests, media, and litigation when formal participation mechanisms fail—indicative of unmet demand for accountability.

Key Constitutional & Legal Linkages

- Article 21 – Right to health as part of Right to Life (Paschim Banga Khet Mazdoor Samity vs State of West Bengal, 1996).

- Directive Principles – Article 38, 39(e), 41, 42, 47 mandate improving public health.

- 73rd & 74th Amendments – Empower local bodies for health and sanitation services.

- National Health Mission Framework – Mandates bottom-up planning with community participation.

Way Forward – Two-Pronged Approach

- Empowering Communities:

- Disseminate health rights awareness.

- Early civic education on health governance.

- Ensure representation of marginalised groups.

- Provide tools/resources for meaningful participation.

- Sensitising Health System Actors:

- Shift from “poor awareness” blame to addressing structural determinants (poverty, access barriers).

- Promote collaborative governance between citizens & health professionals.

Assuaging concerns

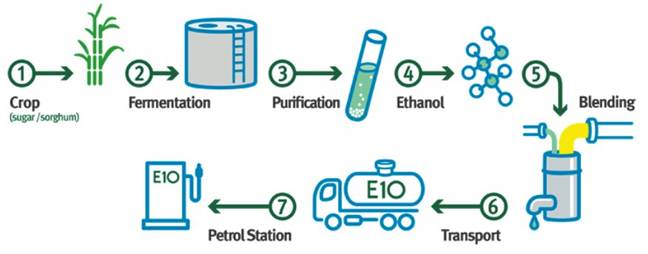

Background: Ethanol Blending in India

- Ethanol blending = mixing ethanol (biofuel) with petrol to reduce fossil fuel use.

- Origins: Introduced globally after the 1970s oil shock to reduce import dependence.

- Global leaders: Brazil (E27+), U.S. (E10–E85 flex-fuel vehicles).

- India’s current target: 20% blending (E20) by 2025.

- Policy rationale in India:

- Import substitution: Save ~$10 billion annually in crude import bills.

- Price advantage: Ethanol is cheaper than petrol (though price benefits not always passed to consumers).

- Carbon footprint reduction: Ethanol is considered carbon-neutral as plant growth offsets emissions during combustion.

Relevance : GS 2(Governance) ,GS 3(Science , Technology , Environment)

Practice Question : Ethanol blending in petrol promises import substitution, carbon reduction, and rural economic benefits, but also raises concerns over vehicle compatibility, consumer protection, and food security. Discuss the key challenges in India’s ethanol blending policy implementation and suggest measures to ensure sustainable and consumer-friendly adoption.(250 Words)

Economic & Agricultural Dimensions

- Feedstock sources in India:

- C-heavy molasses (by-product of sugar industry, not used for sugar production).

- Broken rice (often surplus, rots in FCI godowns).

- Maize (lower input crop; less water and fertiliser-intensive than sugarcane).

- Food security concern:

- If ethanol demand grows rapidly, crop allocation could shift from food to fuel.

- In shortage years, prioritising fuel production over PDS foodgrain supply may create conflict.

- Import substitution limitations:

- Fertiliser imports (~$10 billion/year) offset some forex savings from ethanol-related crude import cuts.

Technical & Vehicle Compatibility Issues

- Efficiency penalty: Ethanol has lower energy density than petrol → reduced mileage.

- Material durability & corrosion: Ethanol can degrade fuel lines, tanks, seals.

- Global compatibility norms:

- Vehicles meeting Euro 2 / U.S. Tier 1 / India’s BS 2 (since 2001) can use up to E15 safely.

- BS 2 mandates closed-loop fuel control systems for optimal combustion & reduced emissions.

- Material upgrades in BS 2 vehicles reduce corrosion risk.

- India’s scenario:

- Vehicles since 2023 are designed for E20.

- Many older models (pre-2023) may be compatible only with E5 or E10.

- No consumer choice at pumps — same fuel for all vehicles.

- Price reduction promised earlier is not visible at retail level.

Regulatory & Standardisation Efforts

- Two ethanol-specific fuel standards already adopted in India.

- Proposed E27 norm (drawing from Brazil’s model) in pipeline.

- Government stance: Internal research shows no significant harm to vehicles.

- Transparency gap:

- Automakers have not clearly disclosed ethanol compatibility of older models.

- Example: Models sold ~5 years ago accepted only E5.

Policy & Consumer Concerns

- Older vehicle owners at risk: May face engine issues or reduced performance without mitigation.

- No voluntary opt-in: Unlike Brazil, India does not offer pure petrol option alongside ethanol blends.

- Insurance protection:

- Risk of claim rejection if engine/fuel system damage attributed to ethanol.

- Editorial urges government-backed insurance guarantees.

- Need for automaker disclosure:

- Public lists of past models and their ethanol tolerance.

- Recommended mitigation steps for incompatible models (e.g., part upgrades).

Policy Recommendations (Editorial + Value Add)

- Transparency: Automakers to publish compatibility lists for older models.

- Mitigation Support: Govt to mandate and facilitate retrofit kits for older vehicles.

- Insurance Protection: Govt-backed claims for ethanol-related damage.

- Feedstock Planning: Dynamic policy to prioritise food over fuel in shortage years.

- Consumer Choice: Separate dispensing lines for E0, E10, E20.

Global Comparisons

- Brazil:

- Flex-fuel vehicles run on 0–100% ethanol.

- E27 is standard at pumps.

- Price incentives for ethanol maintained consistently.

- USA:

- E10 widespread; E85 (85% ethanol) available for flex-fuel vehicles.

- EU:

- E10 is common; strict sustainability criteria for biofuels.

Editorial’s Central Argument

- Ethanol blending is economically & environmentally beneficial but:

- Must be implemented with consumer protection, transparency, and choice.

- Full disclosure by manufacturers is necessary.

- Government must underwrite risks for vehicle owners, especially with older vehicles.

- Price benefits must reach the consumer at the pump.