Content

- UNESCO recognition for Kerala’s Varkala Cliff sparks celebration — and unease

- India to hold mega drone drill ‘Cold Start’ next month

- The mapping of the India-China border

- How Trump’s H-1B fee threatens India’s IT firms and Big Tech business models

- SC links sense of ‘stagnation’ in lower judiciary to long litigation

- India to submit updated carbon-reduction targets by the beginning of COP30 on Nov. 10

- L-1 visa vis-à-vis the H-1B

UNESCO recognition for Kerala’s Varkala Cliff sparks celebration — and unease

Why is it in the news

- UNESCO recognition: Kerala’s Varkala Cliff added to UNESCO’s tentative World Heritage list.

- Significance: Acknowledges its geological, ecological, and cultural value, drawing national and international attention.

- Sparks debate over tourism, climate risks, and governance for fragile heritage sites.

Relevance:

- GS I (Geography & Culture): Coastal geomorphology, laterite cliffs, sacred landscapes, human-environment interaction.

- GS III (Environment & Disaster Management): Coastal ecosystem conservation, climate change impacts, sustainable tourism.

- GS II (Governance & Policy): Heritage management, regulatory frameworks, stakeholder participation, eco-tourism policy.

Understanding Varkala Cliff

- Location: Varkala, Kerala, along the Arabian Sea coast.

- Geological significance:

- Only place in Kerala where cliffs rise directly against the sea.

- Formed during the Mio-Pliocene age; millions of years old.

- Composed of laterite and sedimentary layers; contains fossils and paleo-climatic evidence.

- Vulnerable to erosion, landslides, and human disturbances.

- Cultural significance:

- Janardana Swamy Temple (over 2000 years old) and Sivagiri Mutt (Sree Narayana Guru) anchor the cliff’s spiritual identity.

- Serves as a site for pilgrimages and sacred rituals.

- Economic significance:

- Tourism hub: guesthouses, cafés, yoga centres, employment opportunities.

- Supports local livelihoods including fisherfolk.

Current Concerns

- Environmental risks:

- Erosion, landslides, and cracks accelerated by monsoons and climate change.

- Sea-level rise and stronger storms threaten stability.

- Tourism pressures:

- Waste accumulation, septic leakage, unregulated construction.

- Narrow paths congested; risk of irreversible geological damage.

- Local community impact:

- Fisherfolk fear displacement and loss of livelihood.

- Economic benefits of tourism may conflict with environmental and cultural preservation.

- Governance issues:

- Weak regulatory oversight, flouted building codes, poor coordination between agencies.

- Proposed geo-park or heritage zone initiatives delayed.

Opportunities from UNESCO recognition

- Global visibility: Enhances research, conservation, and responsible tourism.

- Funding & technical support: Access to UNESCO advisory, heritage management frameworks.

- Education & awareness: Schools and NGOs can promote geological, ecological, and cultural knowledge.

- Policy impetus: Encourages Kerala to develop a comprehensive management plan including carrying capacity studies and climate adaptation strategies.

Strategic Implications

- Environmental governance:

- Recognition can act as a catalyst for stricter enforcement of building codes and waste management.

- Encourages science-based climate adaptation and erosion control.

- Tourism policy:

- Necessitates sustainable tourism models, zoning, and controlled visitor flows.

- Balancing economic benefits with preservation is crucial.

- Social equity:

- Fisherfolk and local communities must be actively involved in conservation decisions.

- Avoid displacement and preserve cultural identity.

Conclusion

- UNESCO recognition is a double-edged sword:

- Celebrates geological, cultural, and economic value.

- Exposes risks from unregulated tourism, climate change, and governance failures.

- Way forward: Define carrying capacity, regulate construction, involve locals, and implement climate adaptation to ensure long-term sustainability.

India to hold mega drone drill ‘Cold Start’ next month

What is happening

- Exercise Name: Cold Start

- Timing: First week of October 2025

- Location: Likely Madhya Pradesh

- Participants: Indian Army, Navy, Air Force; includes industry partners, R&D agencies, academia, and other stakeholders

- Focus: Testing drones and counter-drone systems, evaluating air defence capabilities and operational readiness

Relevance:

- GS III (Internal Security & Defence): Modern warfare preparedness, drone and counter-drone technology, integrated tri-service exercises.

- GS III (Science & Technology): UAV systems, GPS-jamming, autonomous aerial platforms, R&D in defence technologies.

Background and Context

- Post-Operation Sindoor: Largest joint drill since Operation Sindoor; previous exercise validated counter-drone and GPS jamming systems.

- Evolving aerial threats: Includes drones, UAV swarms, and GPS-jamming threats from potential adversaries.

- Reference to Pakistan: Exercise aims to stay ahead of adversary capabilities, acknowledging that adversaries also learn from India’s operational experiences.

Strategic Importance

- Operational Readiness: Ensures the integrated response of Army, Navy, and Air Force to aerial threats.

- Force Multipliers: Counter-drone systems, GPS-jamming technologies, and advanced surveillance increase defensive and offensive capabilities.

- Inter-service synergy: Joint exercises enhance coordination, intelligence sharing, and rapid response across services.

Technological and R&D Dimensions

- Focus on innovation: Inclusion of industry, academia, and R&D agencies ensures testing of state-of-the-art technologies.

- Drone and counter-drone systems: Likely tests detection, interception, neutralization, and electronic warfare capabilities.

- Future warfare preparation: Exercise aligns with modern warfare trends emphasizing unmanned systems and autonomous aerial platforms.

Implications for National Security

- Airspace dominance: Enhances India’s defensive posture against UAV and drone threats, especially near sensitive borders.

- Deterrence signal: Demonstrates capability to neutralize aerial threats, sending a message to adversaries.

- Learning and adaptation: Feedback from the exercise will inform procurement, strategy, and capability development, ensuring readiness against emerging threats.

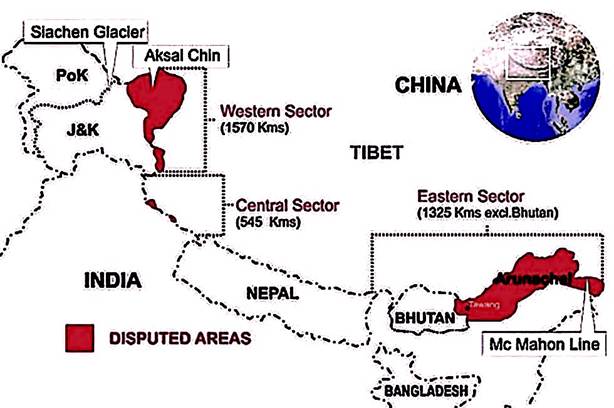

The mapping of the India-China border

Historical Background: The Basis of the Border

- Manchu Rule (1644–1911):

- Two major maps drawn with European Jesuit assistance:

- Kang-hsi Map (1721): Tibet-Assam segment; Tibet considered only up to the Himalayas; Tawang (south of Himalayas) not Tibetan.

- Ch’ien-lung Map (1761): Eastern Turkestan-Kashmir segment; Eastern Turkestan not conceived as trans-Kunlun; southern desolate region not claimed.

- Two major maps drawn with European Jesuit assistance:

- 1913–14 Simla Conference:

- RoC delegate accepted non-Tibetan tribal belt (present Arunachal Pradesh) was not Tibetan.

- India included it in Assam; outcome consistent with Kang-hsi’s map.

- Implication: Traditional Chinese claims were limited; historical maps did not support trans-Himalayan claims in Arunachal Pradesh or Aksai Chin.

Relevance:

- GS II (International Relations & Security): India-China boundary disputes, historical treaties, diplomatic negotiations.

- GS I (Geography & History): Geopolitical importance of Arunachal Pradesh and Aksai Chin, historical mapping.

- GS III (Security): Strategic implications of border management, principle-based negotiation, territorial sovereignty.

Evolution of Chinese Claims

- 1943: RoC sets aside Manchu maps; claims large Indian territories during WWII.

- Justification: map described as “unprecise draft.”

- December 1947: Similar map used amid India-Pakistan conflict.

- Pattern: China inherited and expanded claim-making from predecessor regimes rather than based on historical precedent.

Post-Independence Diplomacy

- 1960 Talks (Jawaharlal Nehru & Chou En-lai):

- Chou questioned India’s historical evidence, using semantic and rhetorical tactics.

- Proposed resolving the boundary not solely on maps, but via principles: equitable, reasonable, dignity-preserving “package deal.”

- Key Insight (Vijay Gokhale, The Long Game):

- Chou avoided suggesting territorial swap (Aksai Chin ↔ Arunachal Pradesh).

- Both sides aimed for comprehensive resolution, integrating boundary, geopolitical, and trade matters.

Specific Boundary Alignments

- 1914 Alignment: Indo-Tibetan boundary in line with Kang-hsi map; acknowledged by both parties at the time.

- 1899 Alignment: Kashmir-Sinkiang boundary line; based on watershed principle; related to Aksai Chin.

Core Principles for Resolution

- Equity & Respect: No defeat to either side; preserve dignity and self-respect.

- Historical Evidence: Manchu-era maps provide strongest evidence for India’s claims.

- Geopolitical Package Approach: Consider boundary settlement along with trade and security issues; possibility of territorial swap remains contingent on mutual security needs.

Key Takeaways

- Historical maps favor India: Manchu-era records clearly delineate Tibet’s southern boundary and Aksai Chin claims.

- China’s modern claims: Largely political opportunism during moments of Indian vulnerability; not supported by historical documentation.

- Diplomatic complexity: Both sides acknowledge need for principles beyond maps to achieve a sustainable, dignified settlement.

- Strategic perspective: India must maintain historical evidence, assert sovereignty, and engage in principle-based negotiations while safeguarding national security.

How Trump’s H-1B fee threatens India’s IT firms and Big Tech business models

Why is it in the news

- Trump administration imposes $100,000 annual fee per H-1B visa to curb labour arbitrage and favour domestic employment.

- Target: Indian IT firms (TCS, Infosys, Wipro) and global tech companies using cheaper foreign labour.

- Impacts new visa applications only; aims to reshape the IT outsourcing and talent ecosystem in the U.S.

- Raises concerns over innovation exodus, competitiveness, and global talent attraction.

Relevance:

- GS III (Economy & Industry): Labour mobility, global IT outsourcing, impact on Indian IT firms, STEM talent flows.

- GS II (International Relations): India-US economic ties, trade, and visa policy implications.

Basics of H-1B visa and context

- H-1B visa purpose: Allows U.S. companies to hire skilled foreign professionals for specialized roles, particularly in IT and STEM.

- Trend: H-1B workers now account for 65% of the U.S. IT workforce (up from 32% in 2003).

- Current issue: Rising H-1B hires coincide with mass layoffs of U.S. graduates in IT-related fields, triggering political and economic scrutiny.

- Existing filing cost: Previously a few thousand dollars per visa; minimal barrier led to “lottery-style” mass applications.

Key drivers behind the policy

- Labour arbitrage: Indian IT firms leverage cheaper foreign engineers for onshore roles, impacting domestic wages.

- Domestic unemployment: 6.1% CS graduates and 7.5% computer engineering graduates remain jobless despite high H-1B usage.

- Political angle: Focus on protecting American workers and curbing displacement by foreign talent.

Implications for Indian IT & Big Tech

- High fee impact: $100K per visa makes hiring foreign engineers onshore economically unviable.

- Strategic choices for IT firms:

- Raise client prices drastically.

- Shift operations offshore, reducing onshore employment opportunities.

- Big Tech: Need for selective hiring; only exceptional candidates will be considered, restoring the original purpose of H-1B.

- Collateral damage: May accelerate operational relocation overseas, potentially hurting U.S. employment instead of helping.

Implications for U.S. innovation & economy

- STEM talent loss: International students contribute $40B+ annually; high fees discourage post-graduation retention.

- Global competition: Canada, Australia, UK actively attract STEM graduates; China’s tech growth increases geopolitical stakes.

- Innovation risk: U.S. risks losing intellectual capital needed for future technological breakthroughs.

- Disproportionate impact: Startups and mid-sized firms face higher barriers than tech giants (Google, Microsoft), potentially consolidating talent among large incumbents.

Policy design critique

- Blunt instrument: Flat fee disregards skill levels, salaries, or elite university background.

- Better alternatives: Tiered fees based on salary, field of research, or U.S. university graduation could target arbitrage without losing top talent.

- Broader implication: Risk of undermining U.S.’s historical role as a global hub for science and technology talent.

Strategic & geopolitical angle

- Global talent mobility: Countries with lower barriers can capture world-class talent.

- U.S. competitiveness: Policy may inadvertently strengthen China, EU, and Commonwealth nations in tech innovation.

- Trade-offs: Short-term labour protection vs. long-term strategic innovation disadvantage.

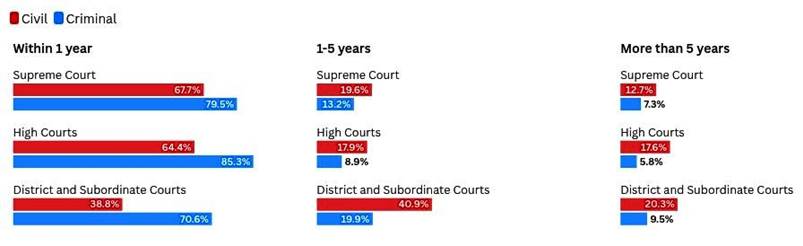

SC links sense of ‘stagnation’ in lower judiciary to long litigation

What is happening

- Event: Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court headed by CJI B.R. Gavai discussed judicial stagnation.

- Issue Highlighted: Weary feeling and stagnation among subordinate judicial officers due to prolonged litigation and career bottlenecks.

- Context of Reference: Whether judicial officers with 7 years’ legal experience can avail Bar quota for District Judge appointments.

- Data on Pendency:

- Total district court cases: 4.69 crore

- Criminal: 3.69 crore, Civil: 1.09 crore (National Judicial Data Grid)

Relevance:

- GS II (Polity & Governance): Judicial structure, career progression in judiciary, access to justice, Articles 32, 226.

- GS II (Law & Ethics): Judicial independence, efficiency, pendency, systemic reforms.

Key Observations by the Bench

- Justice M.M. Sundresh:

- Stagnation undermines the vitality of district judiciary, which is part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

- Example: Bright law clerks hesitant to join judicial service due to uncertain career progression.

- Weak base in district judiciary → multiplication of litigation.

- Lawyers can accomplish in 5 years what judges do in 1 year on the Bench, indicating overburden and inefficiency.

- CJI B.R. Gavai:

- Difficulty attracting talent due to perceived long stagnation before promotion.

- Many capable officers do not become principal district judges even after 15–16 years.

Underlying Issues

- Career Stagnation: Lack of timely promotion in subordinate judiciary reduces professional motivation.

- High Pendency: Over 4.69 crore pending cases strain the judiciary, particularly district courts, affecting public access to justice.

- Impact on Talent: Talented law graduates and clerks hesitant to join judicial service.

- Systemic Bottlenecks: Delay in appointments, promotions, and streamlined career progression.

Constitutional and Institutional Relevance

- District Judiciary: Vital for a healthy justice system; considered part of basic structure.

- Access to Justice: Weak base → delayed justice, undermining Article 21 (Right to Life & Liberty) and public trust in judiciary.

- Judicial Independence & Efficiency: Stagnation risks demoralizing officers, reducing effectiveness and independence.

Broader Implications

- Quality of Judicial Service: Stagnation impacts the professional standards and effectiveness of judges.

- Litigation Multiplication: Weak lower judiciary leads to case pile-up in higher courts, aggravating pendency.

- Policy Gap: Need for career planning, promotion reforms, and Bar quota clarity to maintain judicial motivation.

- Talent Retention: Ensuring attractive career trajectory crucial to draw best talent into public service.

India to submit updated carbon-reduction targets by the beginning of COP30 on Nov. 10

Why is it in the news

- India will submit its updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) at COP30 in Brazil on November 10, 2025.

- Expected to include increased energy efficiency targets and reinforce climate commitments.

- COP30 presidency (Brazil) emphasizes assessment of gaps in NDC achievement globally.

- Submission is timely as only 30 out of 190+ countries have submitted updated NDCs so far.

Relevance:

- GS III (Environment & Climate Change): NDCs, Paris Agreement, emissions intensity, renewable energy targets.

- GS II (International Relations & Governance): Climate diplomacy, COP negotiations, global climate commitments.

- GS III (Economy & Energy): Carbon markets, energy transition, policy interventions in 13 major sectors.

Understanding India’s NDCs

- NDC Definition: Nationally Determined Contributions are country-specific climate action commitments under the Paris Agreement.

- India’s 2022 NDCs:

- Reduce emissions intensity of GDP by 45% (2005 levels).

- Source 50% of electric power capacity from non-fossil fuels by 2030.

- Create a carbon sink of at least 2 billion tonnes by 2030.

- Key Terminology:

- Emissions intensity of GDP: Carbon emissions per unit of GDP; does not equal absolute emission reduction.

- Non-fossil fuel capacity: Renewable energy (solar, wind, hydro, nuclear).

- Current Status (2023):

- 33% reduction in GDP emissions intensity (2005–2019).

- 50% of installed power capacity from non-fossil sources.

Significance of Updated NDCs (NDC 3.0)

- Operational timeline: Likely to indicate targets for 2035.

- Carbon Market: India aims to operationalize the India Carbon Market by 2026 for 13 major sectors, enabling emission trading via reduction certificates.

- Global assessment: Updated NDCs feed into the UN ‘synthesis report’ to evaluate whether collective efforts are sufficient to meet Paris Agreement goals (well below 3°C warming).

Global Context

- EU: No formal 2035 target yet; indicative reduction 66.25%–72.5% (1990 levels). Long-term goal: net zero by 2050.

- Australia: Updated NDC aims to cut emissions by 62%–70% of 2005 levels by 2035.

- Global gap: Even if all NDCs are perfectly met, world is projected to heat by 3°C, missing Paris target of well below 2°C.

Strategic and Policy Implications

- Energy Transition: Higher energy efficiency and non-fossil power targets reinforce India’s climate leadership.

- Market Mechanism: Carbon market encourages corporate participation, incentivizes emissions reduction, and integrates economic tools with climate goals.

- International Diplomacy: Timely and ambitious NDC submission strengthens India’s position in global climate negotiations.

- Domestic Implementation: Targets will require policy interventions across 13 sectors, technology upgrades, and regulatory enforcement.

Challenges

- Achieving absolute emission reduction while sustaining economic growth.

- Sectoral compliance: Ensuring carbon market operations are effective across industries.

- Global comparison: Need to match or exceed peers’ commitments to maintain credibility in climate diplomacy.

- Monitoring and Reporting: Accurate data collection and progress reporting to UNFCCC is critical.

L-1 visa vis-à-vis the H-1B

Why is it in the news

- The US administration imposed a $100,000 fee on fresh H-1B applications, prompting companies and workers to explore alternative work visas.

- The L-1 visa is being discussed as a potential alternative for certain employees of multinational companies.

- Policy relevance: Could affect Indian IT firms, Big Tech, and global talent mobility.

Relevance:

- GS II (International Relations & Policy): US visa policies, bilateral labour mobility implications.

- GS III (Economy & Industry): Global talent mobility, Indian IT and Big Tech staffing strategies, international labour arbitrage.

Understanding the L-1 visa

- Definition: L-1 is a non-immigrant intra-company transfer visa for executives, managers (L-1A), or employees with specialized knowledge (L-1B).

- Eligibility:

- Must have worked abroad for the same multinational firm for at least 1 continuous year in the past 3 years.

- Only the employer can petition; individuals cannot apply independently.

- Duration:

- L-1A: 7 years max (executives/managers)

- L-1B: 5 years max (specialized knowledge employees)

- Advantages:

- No lottery or quota; can apply year-round.

- “Blanket petitions” allow faster processing for large firms.

- L-1 holders can pursue a green card without jeopardizing status.

- Limitations:

- Tied to a single company; cannot switch employers freely.

- Not available to F-1 students (lack of prior international work experience).

- Cannot extend simply while awaiting a green card beyond allowed period.

L-1 vs H-1B: Key Comparisons

| Feature | L-1 | H-1B |

| Purpose | Intra-company transfers | Specialty occupation workers |

| Eligibility | 1 year abroad in same firm | Bachelor’s degree or higher in relevant field |

| Cap / Quota | No cap | 85,000/year (65k regular + 20k advanced degree) |

| Lottery | No | Yes |

| Prevailing wage | Not required | Required |

| Duration | L-1A: 7 yrs, L-1B: 5 yrs | Initial 3 yrs, max 6 yrs |

| Employer flexibility | Tied to same company | Can switch employers with new petition |

| Green card | Allowed, does not jeopardize status | Allowed, but may require extensions for pending GC |

| Student eligibility | F-1 ineligible | Optional through H-1B post-F-1 OPT |

- Conclusion: L-1 is not a blanket substitute for H-1B; it is specialized for multinational transfers, advantageous for eligible employees but limited in scope.

Current Data

- L-1 issuance (US State Dept):

- FY2019: 76,982

- FY2021 (pandemic low): 24,863

- FY2023: 76,571

- Refusal rates increased from ~7% to 12% in 2023.

Strategic & Policy Implications

- For Indian IT and Big Tech firms:

- May rely more on L-1 transfers for eligible employees to mitigate the $100,000 H-1B fee.

- Encourages offshore staffing models for employees ineligible for L-1.

- Talent mobility: L-1 ensures retention of highly skilled employees within multinational structures.

- US perspective: Maintains focus on protecting domestic labor while still allowing multinational firms to bring experienced talent.

- Global competition: Other countries (Canada, Australia, UK) may attract H-1B-eligible workers unable to use L-1.