Content

- Eight killed in stampede at temple in Haridwar

- How is India preparing against GLOF events?

- India’s emerging shield against the climate crisis

- Chola Democracy Before Magna Carta

- India’s Cheetah Diplomacy in Africa

Eight killed in stampede at temple in Haridwar

What Happened

- Date & Time: Morning of July 27, 2025, around 9 a.m.

- Casualties: 8 killed, 30 injured in a stampede at Mansa Devi Temple, Haridwar.

- Cause (Preliminary): Rumour of a snapped electric wire triggered mass panic during peak footfall.

Relevance : GS 3(Disaster Management)

Geographic and Structural Context

- Location: Mansa Devi temple sits 1,770 feet above sea level in the densely forested Shivalik Hills of Uttarakhand.

- Access Path: Narrow stairways and barricaded routes became choke points.

- Weather & Terrain: Monsoon season + slippery pathways likely worsened crowd management challenges.

Demographics of Victims

- Victims aged between 12–60 years.

- Pilgrims hailed from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Uttarakhand, indicating regional religious magnetism.

Administrative Failures

- No Real-Time Crowd Regulation: Absence of responsive crowd control personnel during critical congestion.

- Lack of Redundancy: No alternate escape paths; single staircase acted as both entry and exit.

- Failure in Risk Communication: The rumour about electric wire went unchecked, causing chaos.

Structural and Policy Dimensions

- Recurring Pattern: India has seen over 300 stampede deaths in religious places in the last two decades.

- Systemic Gaps:

- No unified National Religious Pilgrimage Safety Protocol.

- Lack of crowd simulation planning, tech-enabled footfall monitoring.

- Poor inter-agency coordination between local police, temple boards, and municipal authorities.

Way Forward

- Mandatory Crowd Management SOPs for high-footfall religious sites.

- AI-based surveillance systems for crowd density alerts.

- Training of temple volunteers in disaster preparedness.

- Legal obligation for religious trusts to conduct structural safety audits during festival periods.

- Pilgrim insurance tied to temple visit registration apps (like Char Dham portals).

How is India preparing against GLOF events?

Recent GLOF Catastrophe in Nepal

- On July 8, 2025, a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) devastated Nepal’s Lende river valley, destroying a China-built bridge and disrupting the Rasuwagadhi Inland Port.

- Flash floods rendered four hydropower plants on the Bhote Koshi river inoperative, cutting 8% of Nepal’s electricity supply.

- Another GLOF occurred hours later in Mustang district; earlier GLOFs in Humla (2025) and Solukhumbu (2024) show a pattern of increasing frequency.

Relevance : GS 3(Disaster Management )

Cross-Border Challenges in Early Warning

- The Lende river flows from Tibet to Nepal—yet no early warning was issued by China despite the lake shrinkage from 63 ha to 43 ha in a day.

- Nepal lacks a bilateral early-warning system with China; growing supra-glacial lakes in Tibet elevate risk further.

- Transboundary glacial watersheds like Lende or Bhote Koshi amplify downstream vulnerabilities and diminish proactive responses.

Historical Recurrence of GLOFs in Nepal

- Major past events: Cirenma Co (1981), Digi Tsho (1985), Tama Pokhari (1998).

- Mitigation attempts at Imja Tsho and Tsho Rolpa involved manual water drawdown above 5,000m—logistically arduous.

- Despite past lessons, institutionalised regional protocols remain absent.

India’s Exposure to GLOFs

- The Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) spans 11 river basins with 28,000 glacial lakes, including 7,500 in India alone.

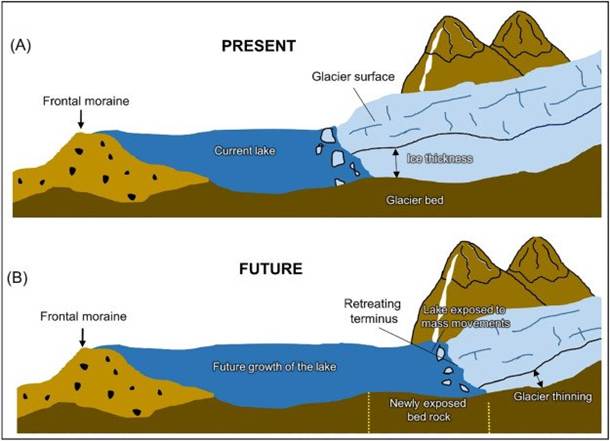

- Two main lake types:

▪ Supraglacial lakes (on glacier surfaces; summer-melt prone).

▪ Moraine-dammed lakes (held by unstable debris; high burst risk).

India’s Risk Landscape

- Two-thirds of GLOFs arise from ice avalanches or landslides; others stem from meltwater pressure or earthquakes.

- Remote high-altitude locations (mostly >4,500 m) hinder direct surveys—limited to summer windows.

- Severe events:

▪ Sikkim’s South Lhonak GLOF (2023): destroyed Chungthang dam (1250 MW), raised Teesta riverbed, worsened flood risk.

▪ Kedarnath disaster (2013): Chorabari GLOF + cloudburst triggered multi-layered devastation.

India’s Mitigation Strategy

- NDMA has adopted a risk-reduction-first model under the Committee on Disaster Risk Reduction (CoDRR).

- First national GLOF mitigation programme launched ($20 million), targeting 195 high-risk glacial lakes in four categories.

- Five-fold focus:

- Lake-specific hazard assessments

- Automated Weather & Water Stations (AWWS)

- Downstream Early Warning Systems (EWS)

- Physical mitigation (drawdown, retention structures)

- Community engagement

Tech & Knowledge Gaps

- Leveraging SAR interferometry to detect micro-slope changes (cm-level) in unstable moraine dams—currently underutilised.

- Limited Indian innovation and tech investment in Himalayan cryosphere resilience.

- Remote sensing (surface area monitoring) remains the only scalable tool, but it’s post-facto, not predictive.

Expedition Insights (Summer 2024)

- Multi-institutional teams visited lakes across J&K, Ladakh, HP, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, and Arunachal.

- Employed:

▪ Bathymetry to measure water volumes.

▪ ERT to detect hidden ice cores in moraine dams.

▪ UAVs and slope stability surveys for terrain mapping. - Installed real-time monitoring stations at two lakes in Sikkim—transmit data every 10 minutes.

- ITBP deployed as manual early warning buffer in the absence of automated systems.

Way Forward

- Monsoon 2025 expeditions already being planned.

- 16th Finance Commission (FY2027–31) expected to scale the GLOF programme across Himalayan states.

- Sustained progress demands:

▪ Institutional cross-border EWS protocols (especially with China).

▪ Local community trust-building.

▪ Private innovation ecosystem for climate-resilient Himalayan infrastructure.

India’s emerging shield against the climate crisis

Context & Urgency

- India faced 764 major natural disasters since 1900, nearly half after 2000 – showing accelerating climate volatility.

- Between 2019–2023, India lost $56 billion to weather-related disasters — the highest in South Asia, ~25% of Asia-Pacific losses.

- Conventional indemnity-based insurance is slow, disputed, and inadequate for sudden climate shocks.

Relevance : GS 3(Disaster Management)

How Parametric Insurance Works

- Pays automatically when pre-defined weather thresholds are breached (e.g. <300 mm rainfall, >40°C, wind speed, seismic activity).

- Based on independently verified datasets from IMD, NASA-MERRA, satellite systems — ensuring objectivity.

- Eliminates the need for damage assessment, enabling rapid liquidity in crisis.

Implementation in India

- Nagaland (2024): First Indian state with multi-year parametric cover for landslides and extreme rainfall.

- Pilots in Rajasthan and U.P.: Protected women smallholder farmers against drought via water balance index.

- Jharkhand: Model proposed for microfinance-linked crop loan protection triggered by rainfall/temperature thresholds.

Global Relevance

- Successfully deployed in Africa, Pacific Islands, U.K. — for droughts, floods, cyclones, even livestock farming.

- Covers modern sectors like solar energy, where policies trigger payouts based on irradiance levels.

Infrastructure in Place

- India already has the climate data ecosystem, digital platforms, and State disaster mitigation funds to scale up.

- Early wins in agriculture, renewables, rural credit, and public disaster finance demonstrate viability.

What India Must Do Next

- Treat parametric insurance as critical climate infrastructure, akin to UPI in payments.

- Expand data networks, integrate into State Disaster Response, embed in climate finance architecture.

- Develop a scalable national framework — pre-approved triggers, digital disbursement, and legal-enforceability.

Strategic Advantages

- Offers speed, transparency, and resilience in an era of climate uncertainty.

- Helps preserve livelihoods, sustain credit cycles, and stabilize local economies during disasters.

- Can de-risk investments in climate-sensitive sectors and support climate adaptation finance under SDGs and Paris goals.

Chola Democracy Before Magna Carta

- Context : PM Modi, speaking at Brihadeeswara Temple, highlighted that India had democratic traditions centuries before the Magna Carta (1215), citing Chola-era electoral practices.

- Uttaramerur Inscriptions (c. 920 CE): These stone inscriptions in Tamil Nadu provide one of the world’s earliest written records of an electoral system.

- Local Governance Framework:

- Sabha: Brahmin-dominated settlements.

- Ur: Non-Brahmin village assemblies.

- Both were elected councils, managing revenue, justice, public works, and temple administration.

Relevance : GS 1(Culture, Heritage ,History)

Kudavolai: The Ballot Pot System

- Procedure:

- Names of eligible candidates written on palm leaves.

- Placed in a pot (kudam).

- A young boy, symbolising impartiality, would draw names publicly.

- Eligibility Conditions:

- Minimum age, education, property ownership, and moral character were prerequisites.

- Exclusions: Women, labourers, and landless individuals — reflective of caste and gender hierarchies of the time.

Decentralised Governance & Civic Autonomy

- Subsidiarity in Action: Empowered village assemblies and merchant guilds (e.g., Manigramam, Ayyavole) formed a bottom-up administrative model.

- Sustainable Administration:

- Cholas used civic systems to extend control, not just military might.

- Historian Anirudh Kanisetti noted the Cholas “engineered legitimacy through local institutions”, contrasting later centralised empires.

Symbolic Statecraft & Strategic Messaging

- Gangajal Episode (1025 CE):

- Rajendra Chola brought Ganges water to his capital, GangaiKonda Cholapuram.

- As per copper plate grants, it was called a “liquid pillar of victory” — blending ritual piety with imperial symbolism.

- Military + Administrative Innovation:

- As Tansen Sen observed, the Cholas excelled not only in naval campaigns but also in creating proto-democratic governance that projected power through order and ritual.

Beyond the Magna Carta

- Western lens on democracy often begins with the Magna Carta and Enlightenment; the Chola model shows alternative civilizational trajectories of governance.

- No modern liberalism, but the institutionalisation of accountability, procedure, and civic duty reflects enduring democratic instincts in Indian polity.

Brihadeeswara Temple – Chola Architectural Marvel

- Built by: Raja Raja Chola I in 1010 CE at Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu.

- UNESCO World Heritage Site: Part of “Great Living Chola Temples” (2004), along with Gangaikonda Cholapuram and Airavatesvara temples.

- Dedicated to: Lord Shiva (as Brihadeeswara or Rajarajeswaram).

- Dravidian Architecture: Noted for its grand scale, symmetry, and granite construction—rare for that region.

- Vimana (tower): Soars to 66 meters, one of the tallest temple towers in India, capped by a single 80-ton granite block.

- Nandi (bull statue): Carved from a single stone, among the largest monolithic Nandi statues in India.

- No binding agents used: Stones interlocked with precision engineering, showcasing Chola mastery in structural design.

- Murals & Inscriptions: Inner walls adorned with Chola frescoes, and inscriptions detail royal donations, military conquests, and temple rituals.

India’s Cheetah Diplomacy in Africa

Project Context and Strategic Relevance

- The Cheetah Reintroduction Project is the world’s first intercontinental large carnivore translocation effort, aiming to restore ecological balance by reintroducing Asiatic cheetahs (extinct in India since 1952).

- It serves as a soft power instrument, enhancing India’s conservation credentials and diplomatic presence in Africa.

- The project aligns with India’s “Act Africa” policy, expanding bilateral ties beyond trade to include biodiversity cooperation.

Relevance : GS 2(International Relations), GS 3(Environment and Ecology)

Bilateral Dynamics with Key African Nations

1. South Africa – A Technically Strong But Politically Shifting Ally

- India signed a 5-year MoU with South Africa in 2022, facilitating the transfer of 12 cheetahs and ongoing veterinary/technical support.

- A post-election regime change in 2024 has led to bureaucratic reshuffling; new officials are reviewing the MoU’s scope and implementation.

- South African wildlife scientists remain engaged, but policy continuity has stalled, creating a diplomatic deadlock flagged in recent NTCA meetings.

- South Africa’s expertise in predator translocation (e.g., lions, leopards) makes it a vital partner, not just a source country.

2. Botswana – A Steady Contributor Despite Regional Volatility

- Botswana has formally committed to sending 4 cheetahs; timelines under discussion.

- With robust wildlife governance and lower political churn, it offers stability and institutional clarity.

- The diplomatic success here reflects India’s proactive engagement and Botswana’s confidence in India’s management of the Kuno habitat.

3. Kenya – A Long-Term Strategic Investment, Not Immediate Source

- No cheetahs yet; focus is on capacity-building, exchange programs, and institutional cooperation (e.g., ranger training, habitat design).

- An MoU expected in March 2025, but talks have remained generic and non-committal regarding cheetah numbers or timelines.

- Kenya’s world-leading expertise in large predator ecology (e.g., Masai Mara) makes it valuable for long-term ecosystem resilience efforts in India.

4. Tanzania and Sudan – On the Radar, but No Formal Engagement

- Steering Committee minutes referenced possible future ties with these nations, but NTCA later clarified no formal progress or MoUs.

- Sudan’s internal instability and Tanzania’s regulatory rigidity pose diplomatic and logistical hurdles.

Institutional and Administrative Coordination

- The National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) is the nodal agency overseeing negotiations, backed by India’s embassies and the Ministry of Environment.

- Madhya Pradesh Forest Department officials have been deployed as field-level diplomats — visiting South Africa to assess protocols, address technical gaps, and pitch India’s preparedness at Gandhi Sagar (future release site).

- Cheetah Project Steering Committee led by Dr. Rajesh Gopal is monitoring international engagement, domestic habitat readiness, and mortality audits.

On-ground Challenges and Ecological Imperatives

- Kuno has witnessed multiple cheetah deaths, raising questions about habitat capacity, prey base, territorial behavior, and disease control — making the need for fresh genetic stock urgent but cautious.

- Experts have raised concerns about carrying capacity saturation, leading to discussions on alternative sites like Gandhi Sagar and Nauradehi.

- Logistical complexities include quarantine protocols, air transport regulations, and veterinary clearances across jurisdictions — all dependent on tight diplomatic synchronisation.

Geopolitical and Developmental Linkages

- The cheetah diplomacy adds to India’s development partnerships in Africa, complementing solar energy (ISA), vaccine diplomacy, and digital skilling programs.

- Africa’s trust in India’s conservation approach bolsters broader South-South cooperation models where biodiversity is a shared priority.

- India’s ability to sustain this project through political transitions abroad reflects a maturing global conservation leadership role, akin to its tiger conservation narrative under Project Tiger.