Content

- More Women Employed in Agriculture, but Half of Them Are Unpaid

- The Wassenaar Arrangement: The Need to Reform Export Control Regimes

- E-Waste Collection Faces Gaps as Informal Sector Plays Huge Role

- Suriname Pledges to Protect 90% of Forests

- India’s Push for Polymetallic Sulphides (PMS) Exploration

More women employed in agriculture, but half of them are unpaid

Basics

- Agriculture = backbone of Indian economy; largest employer of women.

- Women now make up 42% of India’s agricultural workforce.

- Women’s employment in agriculture surged 135% in past decade, as men moved to non-farm jobs.

- Yet, participation has not translated into higher incomes or recognition.

Relevance

- GS-1 (Society):

◦ Gender issues, women’s participation in rural economy.

◦ Social inequality, unpaid labour, empowerment gaps. - GS-2 (Governance, Social Justice):

◦ Policies for women farmers, FPOs, SHGs, digital inclusion initiatives.

◦ Land rights, credit schemes, gender budgeting, legal recognition of women as farmers. - GS-3 (Economy, Agriculture):

◦ Feminisation of agriculture, wage gaps, labour productivity.

◦ Agri-export potential (India–UK FTA), value chains, high-margin crops.

Current Situation

- Unpaid Labour: 1 in 3 working women is unpaid; unpaid women in agriculture rose from 23.6 million to 59.1 million in 8 years.

- Regional Inequities: Bihar & UP → >80% women in agriculture, >50% unpaid.

- Systemic Barriers:

- Only 13–14% landholdings owned by women.

- 20–30% wage gap vis-à-vis men.

- Limited asset ownership, credit, decision-making power.

- Macroeconomic Picture: Despite rising participation, agriculture’s GVA share fell from 15.3% (2017-18) to 14.4% (2024-25) → feminisation reinforced inequities.

Opportunities

- Global Trade Shifts

- India–UK FTA → projected 20% boost in agri exports in 3 years; >95% products duty-free.

- Women-heavy value chains: rice, spices, dairy, ready-to-eat foods.

- Export-oriented growth can transition women from labourers → entrepreneurs.

- Value-Addition & Premium Markets

- High-margin areas: processing, packaging, branding, exporting.

- Growth sectors: tea, spices, millets, organics, superfoods.

- Tools: Geographical Indications (GI), branding, export standards.

- Digital Innovations

- Platforms: e-NAM, mobile advisories, precision farming apps, voice-assisted tech.

- Formalises women’s labour + expands credit, schemes, pricing access.

- Examples:

- BHASHINI, Jugalbandi → multilingual, voice-first government access.

- L&T Digital Sakhi → digital literacy training for rural women.

- Odisha’s Swayam Sampurna FPOs, Rajasthan’s Mahila Kisan Producer Company, Assam tea-sector training.

Challenges

- Structural: Low digital literacy, language barriers, lack of devices.

- Institutional: Weak recognition of women as farmers → exclusion from schemes/loans.

- Economic: Wage gap, landlessness, invisibility of unpaid work.

- Cultural: Male dominance in decision-making, gendered stereotypes in farming roles.

Reforms & Solutions

- Land & Labour Reforms

- Joint/individual land ownership for women.

- Legal recognition as “farmers” → eligibility for credit, insurance, government support.

- Institutional Support

- Expand women-centric FPOs/SHGs with export orientation.

- Credit schemes, gender-responsive budgeting, targeted subsidies.

- Digital Inclusion

- Subsidised smartphones/devices, local language interfaces, AI-powered advisory systems.

- Scale up models like Digital Sakhi, BHASHINI, Jugalbandi.

- Trade & Value Chain Integration

- Embed gender provisions in FTAs (training, credit, market linkages).

- Promote women-led branding & GI-tagged exports.

Implications

- Structural Game-Changer: Women-led agricultural development can address both economic growth and social equity.

- Economic Potential: Unlocking women’s contributions in high-value agri chains can add significantly to exports, GVA, and rural incomes.

- Global Context: With climate change and shifting trade, resilient, inclusive, and sustainable agriculture needs women at the core.

- Governance Dimension: Recognition, legal empowerment, and digital inclusion are critical for sustainable transformation.

- Social Impact: Enhances food security, reduces poverty, empowers households, and improves child welfare (education, nutrition).

Conclusion

Women’s rising presence in agriculture must not reinforce invisibility but instead unlock transformative potential.

- Path forward: recognition, ownership, digital access, and trade-linked empowerment.

- A women-led agri model is not just about social justice; it is a strategic economic imperative for India’s global ambitions.

The Wassenaar Arrangement: the need to reform export control regimes

Basics

- Wassenaar Arrangement (WA):

- Multilateral export control regime (est. 1996).

- Members: 42 states (India joined in 2017).

- Aim: prevent proliferation of conventional arms and dual-use goods/technologies.

- Operates via voluntary coordination: states adopt common control lists, but implementation depends on domestic laws.

- Traditional focus:

- Physical exports → devices, chips, hardware, software modules.

- Military and WMD-use technologies.

Relevance

- GS-2 (International Relations, Governance):

◦ India’s multilateral commitments, export control regimes.

◦ Cybersecurity diplomacy, human rights in tech governance. - GS-3 (Security, Science & Technology):

◦ Dual-use technologies, AI/cloud exports, intrusion software, surveillance risks.

◦ Strategic implications for national and global security.

Contemporary Challenge

- Cloud & AI realities:

- “Export” ≠ physical transfer anymore → remote access, API calls, SaaS, cloud hosting.

- Example: Microsoft Azure, AWS — global backbones where a user in one country can access sensitive capabilities hosted elsewhere.

- Digital surveillance & intrusion tools now used in repression, profiling, and cyber warfare.

- Gap: WA control lists don’t clearly treat cloud services, SaaS, AI models as “exports.”

- Result: grey zones → states exploit loopholes; surveillance tech proliferates without oversight.

Why Reform is Needed ?

- Human Rights Risks

- Cloud-based surveillance → mass profiling, repression (e.g., Israel–Palestine debates, authoritarian regimes).

- Dual-use: “intrusion software” could aid both cyber defence & authoritarian crackdowns.

- Geopolitical Stakes

- Some states benefit from surveillance exports → resist reform.

- National laws differ → fragmented enforcement.

- Structural Weakness of WA

- Voluntary nature → uneven application.

- Consensus requirement → one state can block updates.

- Patchy coverage: e.g., EU has dual-use rules, U.S. EAR stricter, others laxer.

Proposed Reforms

- Expand Scope

- Explicitly include cloud infrastructure, SaaS, AI systems, biometric databases, cross-border data transfers in control lists.

- Binding Obligations

- Move beyond voluntary → mandatory treaty with minimum standards, export denial in atrocity-prone regions.

- End-Use Controls

- Licensing based not only on tech specs but on user identity, jurisdiction, human rights risk.

- Agility & Oversight

- Create a technical committee/secretariat to fast-track updates.

- Sunset clauses: periodic review & removal/addition of items.

- Global Information-Sharing

- Shared watchlists of flagged customers/entities.

- Real-time red alerts on misuse.

- Accountability Mechanisms

- Corporate human rights duties, procurement restrictions on violators.

- Peer review to check national implementation.

India’s Position

- Joined WA in 2017; incorporated lists into domestic framework.

- Engagement has been legitimacy-driven, not reformist.

- Opportunity for India:

- Position itself as advocate of human rights–sensitive tech governance.

- Push for inclusion of AI, cloud, and surveillance exports.

- Balance innovation and sovereignty concerns with global responsibility.

Implications

- WA relevance eroding → designed for hardware era, now facing cloud/AI surveillance.

- Risks of inaction → authoritarian regimes exploit loopholes, global human rights abuses.

- Reform obstacles → geopolitical rivalries, innovation fears, sovereignty claims.

- Pragmatic path:

- Incremental expansion of control lists.

- Align with EU’s dual-use regulation.

- Build coalitions of like-minded states (EU, India, Japan) to press reform.

Conclusion

- WA must evolve from hardware-centric export controls to cloud & AI governance.

- Without reform, it risks irrelevance in an era where surveillance, digital repression, and cross-border data exploitation are primary threats.

- For India, engaging proactively in reform debates offers strategic leverage as both a tech hub and a responsible democracy.

E-waste collection faces gaps as informal sector plays huge role

Basics

- Definition: E-waste = discarded electronic & electrical equipment (EEE) like mobiles, laptops, fridges, batteries.

- India’s Position: World’s 3rd largest generator of e-waste (after China & USA).

- Quantum: 4.17 million metric tonnes in 2022 → surged 73% by 2023-24 to 7.23 MMT approx (official + unofficial).

Relevance

- GS-3 (Environment & Ecology, Economy):

◦ E-waste management, circular economy, sustainable resource recovery.

◦ Strategic materials (rare earths), reducing import dependency, domestic recycling potential. - GS-2 (Governance):

◦ E-Waste Management Rules, Extended Producer Responsibility, policy compliance and audits.

Policy Framework

- Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): Manufacturers responsible for collection & recycling of end-of-life products.

- E-Waste Management Rules, 2016 (amended 2022): Formalized collection targets, introduced EPR certificates, banned unscientific dismantling.

- ₹1,500 crore mineral recycling scheme (2025): To boost rare earths & strategic metals recovery.

- CPCB Portal: Tracks EPR compliance & audits.

Current Challenges

- Informal Sector Dominance: Handles 90–95% of e-waste via unsafe methods (open burning, acid leaching).

- Low Formal Recycling: Only ~43% of e-waste recycled formally despite growth in facilities.

- Health Hazards: Informal workers exposed to lead, cadmium, mercury, brominated plastics.

- Data Gaps: No uniform inventory system; mismatch in national vs global estimates.

- Paper Trading under EPR: Fake reporting of recycling for incentives.

- Traceability Issues: Lack of downstream tracking of recovered materials → leakage back into informal streams.

Economic & Strategic Dimensions

- Resource Value: E-waste contains copper, aluminum, gold, silver, palladium, rare earth elements (REEs).

- Supply Chain Risks: Global fragility + China’s curbs on REE exports heighten India’s strategic vulnerability.

- Potential: India could meet 70% of REE demand in 18 months with strong policy & industry integration (Attero).

- Circular Economy Gap: Repair-focused informal operations prevent materials recovery → undermines resource security.

Social Dimensions

- Livelihoods: Informal sector employs ~95% of workforce in e-waste handling.

- Integration Need: Skilling, EPR floor pricing, and cooperative models needed for inclusion.

- Best Practice: “Mandi-style” aggregation models by firms like Attero to link informal collectors with formal recyclers.

Way Forward

- Inventory & Audits: Standardized national inventory; third-party audits for EPR compliance.

- Technology Scale-up: Investment in hydrometallurgical & pyrometallurgical recycling facilities.

- Integration of Informal Sector: Training, social security, microcredit, buy-back systems.

- EPR Reform: Floor pricing for EPR credits; strict penalties for paper trading.

- Policy Push: Incentivize domestic rare-earth recycling to reduce import dependence.

- Awareness & Consumer Role: Incentives for take-back, deposit-refund systems, repair-to-recycle pipelines.

Suriname pledges to protect 90% of forests

Basics

- Country: Suriname, small South American nation, ~93% forest cover.

- Recent Pledge: Commit to permanently protect 90% of its tropical forests.

- Context: Announced during Climate Week, New York, ahead of COP30 (Belem, Brazil).

- Significance: Surpasses the global 30×30 target (protect 30% of land and oceans by 2030).

Relevance

- GS-1 (Environment & Ecology):

◦ Forest conservation, biodiversity protection, carbon sinks, climate change mitigation. - GS-2 (International Relations, Governance):

◦ Global climate commitments, COP30, 30×30 target, international funding & cooperation.

Forest & Climate Context

- Forest Coverage: 93% of land heavily forested → one of the highest in the world.

- Carbon Sink Status: Suriname is one of only three countries worldwide absorbing more CO₂ than it emits.

- Biodiversity:

- Jaguars, tapirs, giant river otters

- 700+ bird species

- Blue poison dart frog

- Role in Climate Mitigation: Preserving intact forests stabilizes global climate, prevents CO₂ emissions.

Policy & Legal Measures

- Conservation Law Updates: Expected by end of 2025 to strengthen forest protection.

- Indigenous & Maroon Land Rights: Potential recognition of ancestral lands to empower local forest stewardship.

- Forest Management:

- Expansion of eco-tourism opportunities

- Participation in carbon credit markets

Financial & International Support

- Donor Commitment: $20 million from environmental coalitions to support forest protection & local jobs.

- Global Leadership: Sets a benchmark for Amazonian countries struggling with deforestation (e.g., Brazil, Peru).

Challenges

- Land Rights Issues:

- Suriname does not legally recognize Indigenous & tribal land rights.

- Local communities crucial for forest protection but currently lack formal authority.

- Illegal Activities:

- Mining, logging, and roadbuilding threaten forests.

- Past international court rulings have been ineffective in halting concessions.

- Implementation Needs:

- Sustainable economic alternatives to extraction for local communities.

- International technical and financial support.

Environmental & Socio-Economic Implications

- Biodiversity Conservation: Protects key species and preserves ecosystem services.

- Climate Mitigation: Maintains a significant carbon sink.

- Local Livelihoods: Supports eco-tourism, carbon markets, and sustainable forestry jobs.

- Global Example: Provides a model for forest-rich nations with high deforestation pressure.

Way Forward

- Legal Recognition: Granting Indigenous and tribal land rights to enable community-led conservation.

- Enforcement: Strengthen monitoring, anti-illegal logging, and mining measures.

- Financial & Technical Support: International funding for alternative livelihoods, monitoring tech, carbon credit integration.

- Integrated Conservation Strategy: Balance biodiversity protection, climate goals, and socio-economic development.

India’s push for Polymetallic Sulphides (PMS) exploration

Basics

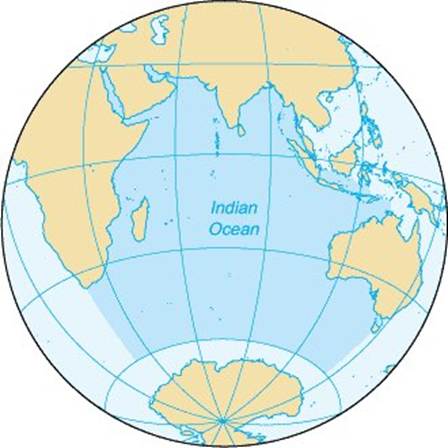

- Topic: India’s push for Polymetallic Sulphides (PMS) exploration in the Indian Ocean.

- Significance: PMS are rich in strategic and critical metals (copper, zinc, lead, gold, silver) essential for renewable energy, green technology, and electronics.

- Historic First: India is the first country to secure two International Seabed Authority (ISA) contracts for PMS exploration, covering the largest area in the world.

Relevance

- GS-3 (Science & Technology, Economy, Security):

◦ Deep-sea exploration, hydrothermal vents, ROV/AUV technology.

◦ Strategic minerals for renewable energy, electronics, EV batteries.

◦ Critical minerals security, reducing import dependence, supply chain resilience. - GS-2 (International Relations):

◦ UNCLOS, International Seabed Authority, maritime law, global positioning of India in seabed mining.

Geographical Context

- Carlsberg Ridge:

- Location: Indian Ocean, between Indian Plate and Somali Plate.

- Features: Rough topography, high mineralization, hydrothermal vents.

- Role: Major source of Polymetallic Sulphides.

- Other key locations: Central Ridge, Mid-Indian Ridge, Madagascar Ridge.

Phases of India’s PMS Exploration

- Phase I – Reconnaissance Surveys:

- Goal: Identify promising PMS sites via seabed surveys and remote sensing.

- Phase II – Targeted Exploration:

- Methods: Conduct near-seabed surveys and ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles) to assess resource potential.

- Phase III – Resource Evaluation:

- Goal: Estimate extractable quantities and assess economic viability.

India’s Previous PMS Exploration

- 2016: NCOPR conducted exploration in Indian Ocean and Southwest Indian Ocean.

- Achievements: Developed expertise in deep-ocean mining, hydrothermal vent mapping, and resource characterization.

- Ongoing research: Ocean Mission programme to enhance deep-ocean exploration capabilities.

Significance of the Carlsberg Ridge

- Geology: High topography, mineralized hydrothermal vent systems.

- Minerals: Rich in copper, zinc, lead, gold, silver.

- Strategic importance: Supports renewable energy, electronics, and green technologies.

- Hydrothermal Activity: Deposits formed by hot fluids interacting with basaltic ocean crust, creating metal-rich chimneys.

How PMS Exploration Differs from Other Underwater Minerals

- Seabed complexity: PMS deposits concentrated near hydrothermal vents; irregular and uneven seafloor makes extraction challenging.

- Dynamic positioning required: Unlike sand or nodules, PMS mining requires precise navigation and site-specific systems.

- Advanced techniques: Geophysical and hydrographic surveys, autonomous vehicles (AUVs and ROVs), sampling, and lab analysis.

Economic & Strategic Importance

- Critical metals: PMS contain copper, zinc, lead, gold, silver essential for EV batteries, electronics, and renewable energy.

- Geopolitical significance:

- Reduces dependence on China for critical metals.

- Positions India as a leader in deep-sea resource exploration.

- Renewable energy transition: Metals support solar, wind, and electric mobility sectors.

International Seabed Authority (ISA)

- Role: Governs resource exploration beyond national jurisdictions.

- India’s position:

- Submitted two PMS exploration applications.

- Follows UNCLOS framework and deep-sea mining protocols.

- Approval process: Requires ISA review and compliance with environmental safeguards.

Challenges

- Technical:

- Deep-sea exploration at ~4000–5000 meters depth.

- Difficult terrain with active hydrothermal vents.

- Environmental:

- Potential disturbance to fragile ocean ecosystems.

- Need for sustainable extraction techniques.

- Financial:

- High capital and operational costs.

- Uncertain global market prices for metals.

Way Forward

- Strengthen domestic capabilities: Advanced ROVs, AUVs, remote sensing, and deep-sea mapping.

- International collaboration: Partner with ISA, research institutes, and technology providers.

- Environmental safeguards: Develop sustainable extraction and monitoring protocols.

- Strategic stockpiling: Use PMS metals to support India’s renewable energy and tech industries.