Content

- Menstrual Health in Schools and the Right to Life

- UGC Equity Rules and Article 15

- Stem Cell Therapy and Autism: Science, Ethics, and Regulation

- CEA Proposal to Ease Green Norms for Pumped Storage Projects (PSPs)

- Illegal Electric Fencing and Emerging Threat to Big Cats

- Recognising Village Commons as a Distinct Land-Use Category

Menstrual Health in Schools and the Right to Life

Why is it in news?

- The Supreme Court held that lack of menstrual hygiene management (MHM) in schools violates Article 21, directing States and Union Territories to ensure free access to sanitary napkins in all schools.

Relevance

- GS 1 (Society): Gender inequality, stigma around menstruation, adolescent health, education access for girls.

- GS 2 (Polity & Governance): Article 21 (Right to Life with dignity), Article 14–15 (equality), positive obligations of the State, judicial activism.

- GS 2 (Social Justice): Child rights, women’s rights, Centre–State responsibility in health and education.

Background and Context

Menstrual health as a public policy issue

- Menstrual hygiene in India has historically been treated as a welfare concern rather than a rights-based issue, resulting in uneven access, stigma, and exclusion in educational institutions.

Judicial intervention

- The Supreme Court adjudicated that inadequate MHM infrastructure in schools leads to humiliation, exclusion, and denial of dignity, directly infringing the constitutional right to life.

Constitutional and Legal Dimension

Article 21 and dignity

- The Court reaffirmed that the right to life under Article 21 includes dignity, bodily autonomy, privacy, and conditions enabling full participation in education without discrimination.

Positive obligations of the State

- The judgment expands Article 21 to impose a positive duty on governments to ensure enabling conditions, not merely prevent direct violations of fundamental rights.

Gender equality linkage

- Inadequate MHM disproportionately affects girls, reinforcing indirect discrimination and violating the constitutional guarantee of equality and non-discrimination under Articles 14 and 15.

Education and Social Dimension

Impact on school participation

- Absence of sanitary products, privacy, and disposal facilities leads to absenteeism, dropouts, and learning gaps among adolescent girls, especially in rural and low-income settings.

Stigma and psychosocial harm

- Menstruation-related stigma in schools results in shame, anxiety, and loss of self-esteem, affecting mental health and long-term educational aspirations of girl students.

Intersection with poverty

- Girls from economically weaker households face compounded disadvantages due to inability to afford sanitary products, making schools critical access points for menstrual health support.

Public Health Dimension

Health consequences of poor MHM

- Lack of safe menstrual hygiene increases risk of reproductive tract infections, urinary infections, and long-term gynaecological health complications.

Preventive healthcare approach

- School-based MHM interventions act as preventive public health measures, reducing disease burden and promoting adolescent health awareness at an early, formative stage.

Governance and Administrative Dimension

Fragmented implementation

- Despite schemes like Menstrual Hygiene Scheme and Swachh Bharat initiatives, MHM implementation remains inconsistent due to weak monitoring and inter-departmental coordination.

Infrastructure gaps

- Many schools lack functional toilets, water supply, disposal mechanisms, and vending facilities, limiting the effectiveness of sanitary napkin distribution alone.

Centre–State responsibility

- Education and health being concurrent/state subjects necessitate coordinated Centre–State action, with judicial directions reinforcing accountability at multiple governance levels.

Ethical and Human Rights Perspective

Menstrual health as human dignity

- Denial of menstrual hygiene facilities amounts to institutionalised indignity, violating ethical principles of justice, equality, and respect for bodily integrity.

Child rights lens

- MHM is integral to children’s rights to health, education, and development, aligning with India’s obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Global and SDG Linkages

International commitments

- Ensuring menstrual hygiene aligns with SDG 3 (Health), SDG 4 (Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), and SDG 6 (Sanitation).

Comparative practices

- Several countries integrate MHM into school health programmes, recognising it as essential infrastructure rather than discretionary welfare support.

Challenges and Gaps

Beyond product-centric approach

- Focus on sanitary napkins alone ignores needs like awareness, waste management, eco-friendly alternatives, and culturally sensitive education.

Urban–rural divide

- Rural schools face greater deficits in infrastructure, awareness, and supply chains, risking uneven compliance with judicial directions.

Sustainability concerns

- Disposal of single-use sanitary products raises environmental concerns, necessitating integration of biodegradable and reusable menstrual products.

Way Forward

Rights-based school MHM framework

- Integrate menstrual health explicitly into the Right to Education ecosystem, treating it as core educational infrastructure rather than auxiliary support.

Holistic MHM strategy

- Combine free product access with functional toilets, water supply, disposal systems, health education, and teacher sensitisation programmes.

Institutional accountability

- Establish monitoring indicators for MHM compliance within school accreditation and education department audits.

Behavioural change and awareness

- Normalize menstruation through curriculum integration and community engagement to dismantle stigma and ensure sustained social acceptance.

Conclusion

- By recognising menstrual health as intrinsic to Article 21, the Supreme Court has shifted the discourse from welfare to rights, making dignified education for girls a constitutional mandate rather than a policy choice.

Article 21: Expanded Spectrum of Rights (Judicial Interpretation)

- Right to live with human dignity – Life means more than mere animal existence; includes dignity, self-worth, and humane conditions of living.

- Right to livelihood – Deprivation of livelihood amounts to deprivation of life (Olga Tellis).

- Right to privacy – Covers bodily autonomy, decisional privacy, informational privacy (Puttaswamy).

- Right to health and medical care – State has a positive obligation to ensure access to healthcare.

- Right to emergency medical treatment – No denial of life-saving care due to procedure or cost.

- Right to clean drinking water – Integral to survival and public health.

- Right to clean and healthy environment – Includes pollution-free air, water, and ecological balance.

- Right to shelter – Includes adequate housing, sanitation, and basic civic amenities.

- Right to education (pre-21A) – Recognised as part of Article 21 before constitutional amendment.

- Right to speedy trial – Delay in justice violates personal liberty.

- Right to legal aid – Essential component of fair procedure and access to justice.

- Right against custodial torture and inhuman treatment – Absolute protection of bodily integrity.

- Right to reputation – An element of dignity and personal identity.

- Right to reproductive choice – Includes bodily autonomy and decisional freedom of women.

- Right to die with dignity – Passive euthanasia permitted under safeguards (Common Cause).

UGC Equity Rules and Article 15

Why is it in news?

- The Supreme Court has stayed the UGC (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulations, 2026, amid challenges alleging “reverse discrimination” and questioning their constitutional basis.

Relevance

- GS 2 (Polity): Article 15(1), 15(2), 15(4), 15(5), substantive equality, reasonable classification, constitutional morality.

- GS 2 (Governance): Regulation of higher education, institutional accountability, role of UGC, preventive anti-discrimination frameworks.

- GS 1 (Society): Caste system, social exclusion, structural discrimination in elite institutions.

Background and Context

Trigger for the 2026 Regulations

- The Regulations emerged from petitions by families of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi, highlighting systemic caste discrimination and institutional failure within higher education campuses.

Core constitutional question

- Whether targeted anti-discrimination safeguards for SC/ST/OBC students violate equality, or instead flow from Article 15’s mandate to remedy historical injustice.

Article 15: Text, Purpose, and Constitutional Philosophy

Article 15(1): Formal non-discrimination

- Article 15(1) prohibits State discrimination on grounds including caste, but by itself addresses only formal equality, not entrenched structural disadvantage.

Article 15(2): Access to public spaces and institutions

- Article 15(2) was specifically designed to counter caste-based exclusion from public institutions, reflecting the Constitution’s awareness of socially embedded discrimination.

Article 15(4) & 15(5): Enabling substantive equality

- These clauses constitutionally authorise special provisions for socially and educationally backward classes, recognising that identical treatment perpetuates inequality.

Substantive Equality Doctrine: Judicial Interpretation

Beyond symmetry in treatment

- The Supreme Court has consistently held that equality under Articles 14–15 is substantive, requiring differential treatment to correct unequal starting positions.

Sukanya Shantha v. Union of India (2024)

- The Court affirmed that law must actively dismantle historical injustice, especially where caste operates as a pervasive social structure influencing institutions.

Relevance to higher education

- Universities are not socially neutral spaces; caste hierarchies reproduce themselves through evaluation, discipline, mentoring, and informal networks, justifying targeted regulation.

UGC Equity Regulations, 2026: Article 15 in Action

Objective of the Regulations

- To promote “full equity and inclusion” in higher education by addressing caste-based discrimination that disproportionately affects historically marginalised groups.

Rational nexus with Article 15

- The Regulations operationalise Article 15 by recognising that caste discrimination is structurally asymmetric, not evenly distributed across social groups.

Why focus on SC/ST/OBC students ?

- Constitutional history and social reality show that caste oppression has been systemic and unidirectional for centuries, warranting corrective institutional measures.

The ‘Reverse Discrimination’ Argument: Constitutional Fallacy

Misreading equality

- Claims of reverse discrimination assume equality means identical protection, ignoring that formal neutrality entrenches substantive inequality.

No constitutional bar on asymmetry

- Article 15 does not mandate equal vulnerability; it mandates equal dignity, which may require unequal safeguards to reach comparable outcomes.

General category protections already exist

- General laws on ragging, harassment, and disciplinary misconduct apply universally, while caste-specific protections address structural exclusion, not isolated misconduct.

Reasonableness Test and Regulatory Validity

Intelligible differentia

- Targeting SC/ST/OBC discrimination rests on clear historical and sociological evidence of systemic vulnerability, satisfying Article 14’s classification test.

Rational connection to objective

- The differential treatment directly advances the goal of equity and inclusion, aligning with constitutional morality rather than arbitrary classification.

Governance and Institutional Accountability

Shift from episodic justice to preventive regulation

- The Regulations move from post-facto redress to institutional prevention, embedding constitutional values into university governance frameworks.

Faculty and administration accountability

- By focusing on institutional responsibility, the Regulations recognise that caste discrimination often flows from power asymmetries, not peer-to-peer interactions alone.

Ethical and Social Dimension

Caste as a lived reality

- Treating caste discrimination as bidirectional ignores its embeddedness in social capital, authority, and evaluation systems, especially within elite educational spaces.

Constitutional morality

- The Regulations reflect Ambedkar’s vision that equality requires state-led correction of inherited disadvantage, not passive neutrality.

Implications of Diluting Article 15 Logic

Risk of reverting to formal equality

- Striking down or weakening the Regulations risks reducing Article 15 to a procedural guarantee, hollowing out its transformative intent.

Chilling effect on marginalised students

- Lack of explicit protections may deepen alienation, silence complaints, and reproduce exclusion, undermining access, retention, and mental health outcomes.

Way Forward

Judicial calibration, not dilution

- The Court may refine definitions or procedural safeguards, but must preserve the substantive equality core rooted in Article 15.

Data-driven institutional mechanisms

- Universities should be mandated to maintain transparent data, grievance redressal systems, and sensitisation programmes aligned with constitutional values.

University Grants Commission (UGC): Value Addition Notes

1. Constitutional & Legal Basis

- UGC derives authority from Entry 66 of Union List (coordination and determination of standards in higher education).

- Established under the UGC Act, 1956, giving it statutory powers to regulate universities.

2. Nature of the Institution

- UGC is a statutory regulatory body, not a constitutional body.

- Functions under the Ministry of Education (Department of Higher Education).

3. Core Objectives

- Maintain uniform standards in higher education.

- Promote access, equity, and excellence in universities.

- Ensure academic autonomy with accountability.

4. Regulatory Powers

- Recognition and de-recognition of universities.

- Prescription of minimum standards for faculty qualifications, infrastructure, and courses.

- Regulation of degree nomenclature and awarding powers.

5. Financial Role

- Disburses grants to Central Universities and eligible institutions.

- Uses funding as a regulatory lever to enforce compliance with standards.

Stem Cell Therapy and Autism: Science, Ethics, and Regulation

Why is it in news?

- The Supreme Court ruled that stem cell therapy cannot be offered as a clinical service for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) due to absence of proven safety, efficacy, and regulatory approval.

Relevance

- GS 3 (Science & Technology): Stem cell technology, limits of biomedical innovation, distinction between research and clinical application.

- GS 2 (Governance): Regulation of medical practice, Clinical Trials Rules 2019, role of central regulatory authorities.

Background and Context

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

- ASD is a neurodevelopmental condition marked by social communication difficulties, repetitive behaviours, and sensory sensitivities, requiring behavioural, educational, and supportive interventions rather than curative biomedical treatment.

Rise of unproven therapies

- In absence of a definitive cure, families often turn to experimental or alternative therapies, creating space for unregulated clinics to promote stem cell “treatments” without scientific backing.

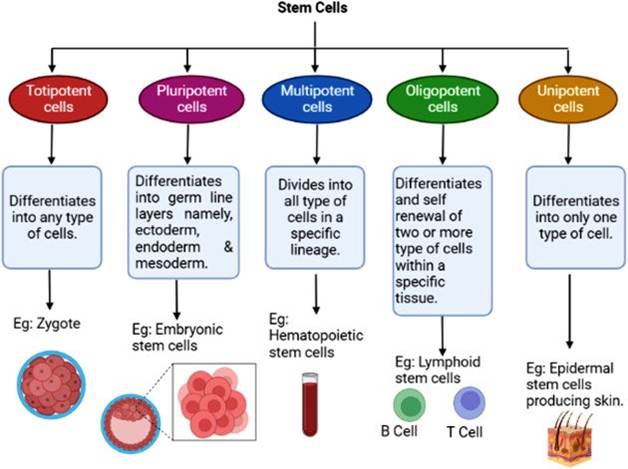

Stem Cell Therapy: Scientific Basics

What is stem cell therapy?

- Stem cell therapy involves using undifferentiated cells with regenerative potential to repair or replace damaged tissues, currently approved only for limited, evidence-backed indications like certain blood disorders.

Status in neurological conditions

- For complex neurodevelopmental disorders like autism, causal pathways are not fully understood, making biological interventions speculative and scientifically unvalidated.

Supreme Court’s Key Findings

Lack of scientific evidence

- The Court noted absence of credible, peer-reviewed evidence establishing safety or therapeutic benefit of stem cell therapy in autism, disqualifying it from routine clinical use.

Distinction between research and treatment

- Experimental interventions may occur only within regulated clinical trials, not as commercial therapies offered to patients under the guise of treatment.

Informed consent is not a substitute for evidence

- Consent obtained without reliable information on risks, benefits, and efficacy is not “informed consent”, especially when patients are vulnerable or desperate.

Regulatory and Legal Framework

Clinical Trials Rules, 2019

- Indian law prohibits offering unapproved therapies outside approved clinical trials, mandating ethics committee clearance, trial registration, and regulatory oversight.

Role of central regulatory authority

- The Court directed the Union government to designate a competent authority to monitor, regulate, and act against unauthorised stem cell interventions nationwide.

Ethical Dimensions

Exploitation of vulnerability

- Parents of children with autism face emotional distress, making them susceptible to false promises of “miracle cures”, raising serious ethical concerns of exploitation.

Medical ethics principles

- Promotion of unproven therapies violates non-maleficence (do no harm), beneficence, and autonomy, as decisions are based on misinformation rather than evidence.

Governance and Public Health Concerns

Patient safety risks

- Unregulated stem cell interventions carry risks of infection, immune reactions, tumour formation, and irreversible harm, with no established benefit to justify exposure.

Regulatory enforcement gap

- The judgment highlights weak enforcement against medical quackery, allowing illegal clinics to flourish despite existing biomedical regulations.

Science Policy Perspective

Evidence-based medicine

- The ruling reinforces that clinical services must be grounded in reproducible scientific evidence, not anecdotal success stories or commercial incentives.

Protecting legitimate research

- By separating research from treatment, the Court safeguards ethical biomedical innovation, ensuring that experimental therapies progress through proper scientific validation.

Implications for Autism Care

Focus on proven interventions

- Autism management must prioritise early diagnosis, behavioural therapy, speech and occupational therapy, inclusive education, and family support, rather than biomedical shortcuts.

Preventing medical misinformation

- Judicial intervention helps curb pseudoscientific narratives, promoting rational health-seeking behaviour and trust in public health systems.

Way Forward

Strengthening regulation

- Establish a national oversight mechanism for stem cell research and therapies, with strict penalties for violations and real-time monitoring of clinics.

Public awareness and counselling

- Government and medical bodies must educate families about evidence-based autism care, risks of unproven therapies, and ethical clinical research pathways.

Core Takeaway

- The Supreme Court’s ruling affirms that medical innovation cannot bypass scientific evidence and ethical safeguards, protecting vulnerable patients from exploitation while upholding the primacy of evidence-based healthcare.

CEA Proposal to Ease Green Norms for Pumped Storage Projects (PSPs)

Why is it in News?

- The Central Electricity Authority (CEA) has proposed easing environmental and forest clearance norms for pumped-storage projects to accelerate capacity addition amid renewable energy expansion and storage shortages.

Relevance

- GS 3 (Environment & Energy): Renewable energy transition, energy storage, climate mitigation vs environmental protection.

- GS 3 (Economy): Infrastructure development, power sector reforms, long-duration storage economics.

Background and Context

India’s Renewable Energy Transition

- India targets 500 GW non-fossil capacity by 2030, requiring large-scale energy storage to manage intermittency from solar and wind, which together form the backbone of future power supply.

Role of Energy Storage

- Grid-scale storage is essential for balancing supply–demand, frequency regulation, and peak-load management, especially as renewable penetration increases beyond conventional grid flexibility limits.

Pumped Storage Projects (PSPs): Basics

What are PSPs?

- PSPs store electricity by pumping water to an upper reservoir during surplus power periods and generating electricity by releasing it downhill during peak demand hours.

Why PSPs matter ?

- PSPs provide long-duration energy storage (6–10 hours), grid inertia, and rapid ramping, unlike batteries which currently face cost and lifecycle constraints at scale.

Current Status of PSPs in India

Installed and Planned Capacity

- India has about 4.8 GW operational PSP capacity, with over 100 GW identified potential, though actual development remains limited due to regulatory and environmental hurdles.

CEA’s Storage Vision

- CEA estimates India will require 336–340 GW of storage by 2047, with pumped storage contributing a dominant share due to scalability and cost efficiency.

Key Problem: Environmental and Forest Clearances

Clearance-related delays

- According to CEA, environmental, forest, and wildlife clearances are the primary reasons for slow PSP development, particularly in ecologically sensitive hill regions.

Protected and Eco-Sensitive Zones

- Many viable PSP sites fall within Eco-Sensitive Zones (ESZs) around protected forests, triggering multi-layered approvals and litigation, delaying projects by several years.

CEA’s Proposed Easing of Green Norms

Differentiation between PSPs and conventional hydro

- CEA proposes treating off-river and closed-loop PSPs separately, recognising their significantly lower ecological footprint compared to conventional river-diversion hydropower projects.

Use of degraded forest land

- The proposal suggests permitting PSPs on degraded forest land, with compensatory afforestation and biodiversity offsets replacing blanket restrictions.

Streamlining approvals

- PSPs may be granted simplified environmental clearance pathways, excluding them from repeated river-basin and cumulative impact assessments where ecological disruption is minimal.

Environmental Impact Assessment: Key Arguments

Lower ecological impact

- Off-river PSPs do not require continuous river flow diversion, resulting in minimal downstream ecological disruption, sediment alteration, or aquatic biodiversity loss.

Limited displacement

- PSPs typically involve smaller submergence areas, reducing large-scale displacement and rehabilitation issues common in conventional hydroelectric projects.

Opposition and Environmental Concerns

Ecological sensitivity of hill regions

- Environmental groups argue PSPs in the Western Ghats, Eastern Ghats, and Himalayas threaten fragile ecosystems, landslide-prone slopes, and forest corridors.

Cumulative impact risks

- Critics warn that multiple PSPs in a single region may cause hydrological stress, deforestation, and wildlife habitat fragmentation, undermining conservation goals.

Governance and Regulatory Dimensions

Balancing climate and conservation goals

- The debate reflects a policy tension between rapid decarbonisation through renewable integration and constitutional environmental protection under Articles 48A and 51A(g).

Institutional coordination challenge

- PSP approvals require alignment among MoEFCC, State governments, power ministries, and wildlife authorities, often leading to procedural bottlenecks and inconsistent decisions.

Economic and Energy Security Implications

Grid stability and peak management

- Accelerated PSP deployment can reduce reliance on coal-based peaking power, cutting emissions and fuel import dependence while stabilising electricity tariffs.

Cost competitiveness

- PSPs offer levelised storage costs lower than lithium-ion batteries for long-duration storage, making them economically attractive for India’s scale requirements.

Global Comparisons and Lessons

International experience

- Countries like China, the US, and Japan treat PSPs as strategic grid infrastructure, with streamlined environmental approvals for closed-loop systems.

Alignment with global trends

- India’s proposal aligns with global recognition of PSPs as enablers of renewable energy transition, not traditional large-dam hydro projects.

Way Forward: Balanced Policy Approach

Environmental safeguards with flexibility

- Adopt site-specific, science-based clearances, prioritising off-river PSPs, cumulative impact studies, and strict post-construction ecological monitoring.

Institutional reforms

- Create a dedicated PSP clearance framework, separate from conventional hydropower, with time-bound approvals and transparent compensation mechanisms.

Core Takeaway

- Easing green norms for pumped-storage projects reflects India’s attempt to reconcile energy transition imperatives with environmental protection, where nuanced regulation, not blanket restrictions, is key to sustainable decarbonisation.

Illegal Electric Fencing and Emerging Threat to Big Cats

Why is it in News?

In January 2026, a 2.5-year-old male tiger was electrocuted by illegal electric fencing near Valmiki Tiger Reserve, marking the first such recorded incident in Bihar’s only tiger reserve

Relevance

- GS 3 (Environment): Wildlife conservation, human–wildlife conflict, landscape-level conservation beyond protected areas.

- GS 3 (Biodiversity): Tiger corridors, buffer zones, conservation challenges in human-dominated landscapes.

Background and Context

Valmiki Tiger Reserve (VTR): Strategic Importance

- VTR, spread over 899 sq km in West Champaran, Bihar, is the state’s only tiger reserve, bordering Nepal and Uttar Pradesh, forming a critical transboundary tiger landscape.

Rising Tiger Population

- Tiger numbers in VTR increased from 28 (2014) to 54 (2024), a 75% rise, earning NTCA’s “Very Good” category, but also increasing human–wildlife interface pressures.

Use of Illegal Power Supply

- Farmers used unauthorised grid electricity, meant for agriculture and domestic use, to energise fences, making them lethal instead of deterrent.

Illegal Electric Fencing: A Growing Conservation Threat

Why Farmers Use Electric Fencing

- Electric fencing is used to deter nilgai, wild boar, and other herbivores damaging rabi crops near forest boundaries, reflecting rising crop-raiding conflicts.

Why It Is Dangerous ?

- Unlike solar-powered low-voltage fences, illegal fencing often carries high-voltage alternating current, causing instant death to large mammals, including tigers and elephants.

Tiger Ecology and Human-Dominated Landscapes

Movement Beyond Protected Areas

- Tigers routinely move into buffer zones, corridors, and agricultural fields, especially young dispersing males, increasing exposure to anthropogenic hazards like fences and roads.

Landscape-Level Conservation Reality

- Modern conservation recognises that over 30–40% tiger movement occurs outside core forest areas, making coexistence measures critical beyond reserve boundaries.

Recognising Village Commons as a Distinct Land-Use Category

Why is it in News?

- Economic Survey 2025–26 proposes recognising “village commons” as a distinct land-use category, enabling systematic mapping, monitoring, and policy intervention to revive degraded common property resources.

Relevance

- GS 1 (Society): Rural livelihoods, common property resources, social safety nets for landless and marginal groups.

- GS 2 (Polity & Governance): 73rd Constitutional Amendment, Gram Sabha powers, decentralised resource governance.

Background and Conceptual Framework

What are Village Commons?

- Village commons are community-managed Common Property Resources (CPRs) such as grazing lands, ponds, tanks, forests, and wastelands used collectively for fodder, fuel, water, livelihoods, and ecosystem services.

Scale and Significance

- Commons constitute ~15% of India’s geographical area (~6.6 crore hectares), supporting ~35 crore rural people, especially landless households, pastoralists, and marginal farmers.

Economic, Social, and Ecological Importance

Livelihood and Rural Economy

- Village commons provide fodder security, fuelwood, water access, minor forest produce, and seasonal employment, acting as a livelihood buffer for vulnerable rural populations.

Economic Valuation

- As per Economic Survey estimates, commons generate an economic dividend of ~USD 9.05 crore annually, though their indirect ecological value remains undercounted in GDP frameworks.

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

- Commons function as biodiversity-rich ecosystems, aiding groundwater recharge, soil conservation, carbon sequestration, and micro-climate regulation.

Governance and Institutional Context

Current Land-Use Classification Gaps

- Village commons are often misclassified as wastelands or revenue lands, making them vulnerable to encroachment, diversion, and neglect in planning processes.

Decentralised Governance Link

- Constitutionally, management of commons aligns with 73rd Constitutional Amendment, Gram Sabhas, and Panchayats, but lack of clear legal status weakens local authority.

Evidence of Decline and Degradation

Land Degradation Trends

- ISRO’s Desertification and Land Degradation Atlas shows degraded land increased from 94.53 million ha (2003–05) to 97.85 million ha (2018–19), adding ~0.22 million ha annually.

Drivers of Degradation

- Encroachment, overgrazing, unregulated pasture use, declining community institutions, groundwater over-extraction, and absence of sewage treatment in villages accelerate commons’ decline.

Why Recognition as a Distinct Category Matters ?

Policy and Planning Advantages

- Formal land-use recognition enables accurate estimation, geo-spatial mapping, targeted funding, and outcome-based monitoring, correcting policy blindness towards commons.

Preventing Conversion and Encroachment

- Legal recognition raises transaction costs for diversion, discourages ad-hoc conversion, and strengthens community claims over shared resources.

Best Practices from States

Karnataka and Rajasthan Models

- Multi-tiered institutional frameworks integrating revenue records, GIS mapping, and Panchayat databases have improved identification, protection, and management of commons.

Lesson for National Scaling

- State experiences show that institutional clarity + digital mapping + community involvement improves commons governance.

Linkages with National Schemes

Ongoing Government Initiatives

- SVAMITVA Yojana: Drone-based mapping of village lands and commons.

- Mission Amrit Sarovar: Rejuvenation of village water bodies.

- PMKSY (Har Khet Ko Pani) & Jal Shakti Abhiyan: Catch The Rain: Restoration of traditional water systems.

Need for Convergence

- Recognised land-use status allows convergence of climate, water, rural livelihood, and land restoration schemes around village commons.

Sustainability and SDG Alignment

SDG Contributions

- Commons directly contribute to:

- SDG 1 (No Poverty)

- SDG 8 (Decent Work & Livelihoods)

- SDG 15 (Life on Land)

Climate Resilience

- Revived commons enhance adaptation capacity against droughts, floods, and climate-induced livelihood shocks.

Challenges and Risks

Institutional Capacity Deficit

- Panchayats often lack technical, financial, and administrative capacity to manage commons sustainably.

Elite Capture and Exclusion

- Without safeguards, commons risk elite capture, marginalising landless households, women, and pastoral communities.

Way Forward: Policy and Governance Reforms

Legal and Institutional Measures

- Formally notify village commons as a land-use category with sub-classifications (pasture, water body, forest commons).

- Strengthen Gram Sabha authority in management, access rules, and dispute resolution.

Technological and Financial Support

- Use GIS, satellite imagery, and drone surveys for real-time monitoring.

- Allocate dedicated restoration funds linked to performance outcomes.

Community-Centric Approach

- Invest in capacity-building of local bodies, revive traditional management norms, and integrate women’s SHGs and user groups.

Core Takeaway

- Recognising village commons as a distinct land-use category marks a shift from land as commodity to land as community capital, essential for rural livelihoods, ecological security, and sustainable development in India.