Contents

- How to win over Kashmiri youth?

- What will a legal guarantee of MSP involve?

How to win over Kashmiri youth?

Context:

Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) has been on the boil since Independence. Several solutions to the problem of militancy have been put forth. Recently, there was a suggestion that de-radicalisation camps should be organised for the youth.

Relevance:

GS-III: Internal Security Challenges (Linkages of Organized Crime with Terrorism)

Dimensions of the Article:

- Radicalization

- Types of Radicalisation

- Radicalisation In J&K

- What is De radicalisation?

- Significance of De-radicalisation Camps

- Challenges associated with Deradicalization Camps

- Examples from other countries

- Solutions to De-radicalisation

Radicalization

- Radicalization is a process by which an individual or group comes to adopt increasingly extreme political, social, or religious ideals and aspirations that reject or undermine the status quo or contemporary ideas and expressions of the nation.

- The outcomes of radicalization are shaped by the ideas of the society at large; for example, radicalism can originate from a broad social consensus against progressive changes in society or from a broad desire for change in society.

- Radicalization can be both violent and nonviolent, although most academic literature focuses on radicalization into violent extremism (RVE).

- There are multiple pathways that constitute the process of radicalization, which can be independent but are usually mutually reinforcing.

- Radicalization that occurs across multiple reinforcing pathways greatly increases a group’s resilience and lethality.

- Furthermore, by compromising its ability to blend in with non-radical society and participate in a modern, national economy, radicalization serves as a kind of sociological trap that gives individuals no other place to go to satisfy their material and spiritual needs

- The Judge Webster Commission 2009 had observed: ‘Radicalism is not a crime. Without exhortation to violence, radicalization alone may not be a threat.’

Types of Radicalisation

- Right-Wing Extremism – It is characterized by the violent defence of a racial, ethnic or pseudo-national identity, and is also associated with radical hostility towards state authorities, minorities, immigrants and/or left-wing political groups.

- Politico-Religious Extremism – It results from political interpretation of religion and the defence, by violent means, of a religious identity perceived to be under attack (via international conflicts, foreign policy, social debates, etc.). Any religion may spawn this type of violent radicalization.

- Left-Wing Extremism – It focuses primarily on anti-capitalist demands and calls for the transformation of political systems considered responsible for producing social inequalities, and that may ultimately employ violent means to further its cause. It includes anarchist, maoist, Trotskyist and marxist–leninist groups that use violence to advocate for their cause.

Radicalisation In J&K

- General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistan’s dictator-President, started the practise of utilising religious overtones in statecraft.

- He emphasised the importance of religion in government policy. During his reign, the development of Madrasas began, and they have played a significant role in the Islamization and radicalization of Pakistani youth.

- Later, as part of low-intensity war activities, this spilled over into Kashmir (LICO).

- Insurgents who wanted J&K to secede from India began using violent measures to achieve their goal in 1989.

- As a result, effective counter-insurgency operations were launched.

- To combat militancy, the Public Safety Act of 1978 and the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act of 1958 were utilised.

- In Pakistan, hundreds of tanzeems (fighting organisations) were formed to fight in Afghanistan. Some of these were later sent to Jammu and Kashmir.

- In the pretext of Islam and Kashmiri liberation, Pakistani operatives went about recruiting young people to train in Pakistan.

- Due to threats from terrorist leaders in the 1990s, many Kashmiri families transferred one of their sons to Pakistan to be trained and subsequently deployed in Kashmir.

- Governor’s rule remained in place in J & K for a long period, effectively suppressing the democratic process.

- Homegrown militancy first emerged in Kashmir during protests over state elections in 2008, and then again when the Indian Army killed three infiltrators in 2010.

- The Hurriyat Conference of All Parties called for violent protests, which led to rioting, the burning of government cars, and “stone-pelting events.”

- With the emergence of homegrown militancy, the situation on the ground deteriorated.

What is De radicalisation?

- Deradicalization is a term used to describe the process of persuading someone with strong political, social, or religious beliefs to take more moderate perspectives on topics.

- Even in the last five years, “deradicalization” initiatives, which are aimed at gently moving people and groups away from violent extremism, have expanded in popularity and reach.

- Deradicalization is the process of separating a person from their extremist beliefs, whether voluntarily or involuntarily.

Significance of De-radicalisation Camps

- Deradicalisation camps are distinct from past approaches to rehabilitation in that they also focus on persons who have not yet committed a terrorist act.

- Deradicalisation camps employ modern approaches such as technology and internet communication, which have been effectively co-opted by terror groups.

- It requires examining if the process can be reversed and how government-led measures can assist in ensuring that committed terrorists do not engage in criminal activities after freed from jail.

- Focusing on rehabilitation makes sense in light of the fact that dedicated ideologues may never abandon their views, but they may modify their conduct.

Challenges associated with Deradicalization Camps

- No standard definition: The terms “terrorism,” “violent extremism,” “radicalisation” and “deradicalisation” are still loosely defined; there is no universal agreement.

- Twin Challenges: There were now twin challenges for the Army, the Central Armed Police Forces and the J&K Police. The first were the terrorists for whom the rules of engagement were different The second were the Kashmiri youth who formed the bulk of the protestors — Indians for whom all the rules and laws applicable to any Indian citizen apply.

- Human Rights Issues: When stone-pelting incidents took a serious and alarming turn, armed personnel responded with pellet guns and other means of riot control. Injuries, especially eye injuries, were a serious fallout of this response which was criticised for Human rights violation.

- Problems of Kashmiri Youths: Kashmiri children in schools and colleges outside the State are often mistreated when any misadventure takes place in J&K. The incidents of violence against minorities, including Muslims, in north India have only worsened problems with Kashmiri youths. The Kashmiri youth feel that they face hostility from the Indian state because of their Muslim identity and so the status quo cannot be effective.

- Similar to Detention Camps: The suggestion of de-radicalisation camps for the youth can appear similar to the detention camps run by China for Muslim minorities.

- Political Threats: This suggestion will be exploited for political gains by the pro-Pakistani elements and further vitiate the atmosphere.

Examples from other countries

- UK: By revising the Counter Terrorism and Security Act (CTSA) in 2009, UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown transformed the country’s counter-terrorism strategy (CONTEST) into a multi-agency approach, making it more transparent and democratic.

- Sri-Lanka: Sri Lanka’s rehabilitation programme to combat violent insurgency, which was started by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), provides valuable insight into both the accomplishments and pitfalls of the deradicalisation programme.

Solutions to De-radicalisation

- Different sectors, such as education, social services, and health, should be assigned defined roles.

- To combat the ‘hate’ ideology, it is necessary to move away from a State-mandated counselling programme and toward a multi-agency-designed educational programme with community and religious backing.

- Elected community officials and faith-based organisations can both play key roles.

- ‘Counter-narratives’ and avoiding internet radicalization are important aspects which can identify and assist susceptible people.

- Individuals at risk should be identified, the nature of the risk assessed, suitable assistance plans developed, and channel support extended or terminated by local government entities.

- As a ‘channel police practitioner,’ the police function has been limited to coordinating.

- Human rights organisations can work to look after infringes on freedom of expression and privacy, particularly in schools.

- Before increasing counter-terrorist capabilities, policymakers must address “unaddressed socio-economic and political reasons” that are accountable for the increase of violence, according to a Brookings research on violent extremism released in March 2019.

-Source: The Hindu

What will a legal guarantee of MSP involve?

Context:

After a year-long agitation on the borders of Delhi, protesting farm unions are pushing for their other major demand for providing a legal guarantee that all farmers will receive remunerative prices for all their crops.

Relevance:

GS-III: Agriculture (Agriculture Pricing), GS-II: Governance (Government Policies & Interventions, Issues arising out of the design and implementation of policies)

Dimensions of the Article:

- How many crops does the minimum support price cover?

- About the prevalent backing for MSP

- What would be the fiscal cost of making the MSP legally binding?

- What is the Government’s position?

- About the success of states guaranteeing MSP rates

Click Here to read more about Minimum Support Price (MSP), its need and issues

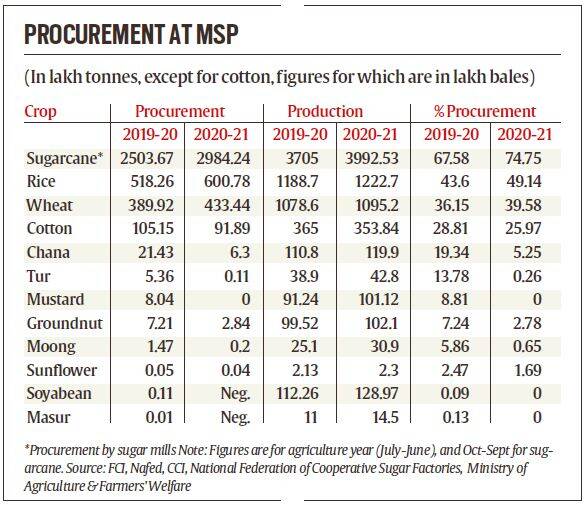

How many crops does the minimum support price cover?

- The Central Government sets a minimum support price (MSP) for 23 crops every year, based on a formula of one-and-a-half times production costs.

- This takes into account both paid-out costs (A2) such as seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, fuel, irrigation, hired workers and leased-in land, as well as the imputed value of unpaid family labour (FL).

- Farm unions are demanding that a comprehensive cost calculation (C2) must also include capital assets and the rentals and interest forgone on owned land as recommended by the National Commission for Farmers.

About the prevalent backing for MSP

- There is currently no statutory backing for these prices, nor any law mandating their enforcement.

- The government only procures about a third of wheat and rice crops at MSP rates (of which half is bought in Punjab and Haryana alone), and 10%-20% of select pulses and oilseeds.

- According to the Shanta Kumar Committee’s 2015 report, only 6% of the farm households sell wheat and rice to the government at MSP rates. However, such procurement has been growing in the last few years, which can also help boost the floor price for private transactions.

What would be the fiscal cost of making the MSP legally binding?

- The MSP value of the total output of all the 23 notified crops worked out to about Rs 11.9 lakh crore in 2020-21. But this entire produce wouldn’t have got marketed.

- The marketed surplus ratio – what remains after retention by farmers for self-consumption, seed and feeding of animals – is estimated to range from below 50% for ragi and 65-70% for bajra (pearl-millet) and jowar (sorghum), to 75-85% for wheat, paddy and sugarcane, 90%-plus for most pulses and 95-100% for cotton, soyabean, sunflower and jute. Taking an average of 75% yields a number – the MSP value of production actually sold by farmers – just under Rs 9 lakh crore.

- All in all, then, the MSP is already being enforced, directly or through fiat, on roughly Rs 3.8 lakh crore worth of produce. Providing legal guarantee for the entire marketable surplus of the 23 MSP crops would mean covering another Rs 5 lakh crore or so.

- The crop that is bought by the government also gets sold, with the revenues from that partly offsetting the expenditures from MSP procurement.

- Secondly, government agencies needn’t buy every single grain coming in to the mandis. Mopping up even a quarter of market arrivals is often enough to lift prices above MSPs in most crops.

What is the Government’s position?

- While announcing the decision to repeal the farm laws, the Prime Minister announced the formation of a committee to make MSP more transparent, as well as to change crop patterns — often determined by MSP and procurement — and to promote zero budget agriculture which would reduce the cost of production but may also hit yields.

- The panel will have representatives from farm groups as well as from the State and Central Governments, along with agricultural scientists and economists.

- Both the Prime Minister and the Agriculture Minister have previously assured Parliament that the MSP regime is here to stay, even while dismissing any need for statutory backing.

About the success of states guaranteeing MSP rates

- A policy paper by NITI Aayog’s agricultural economist Ramesh Chand, which is often quoted by Agriculture Ministry officials, argues, “Economic theory as well as experience indicates that the price level that is not supported by demand and supply cannot be sustained through legal means.”

- It suggests that the States are free to guarantee MSP rates if they wish, but also offers two failed examples of such a policy.

- One is in the sugar sector, where private mills are mandated to buy cane from farmers at prices set by the Government. Faced with low sugar prices, high surplus stock and low liquidity, mills failed to make full payments to farmers, resulting in an accumulation of thousands of crores worth of dues pending for years.

- The other example is a 2018 amendment to the Maharashtra law penalising traders with hefty fines and jail terms if they bought crops at rates lower than MSP. “As open market prices were lower than the (legalised) MSP levels declared by the State, the buyers withdrew from the market and farmers had to suffer,” says the paper, noting that the move was soon abandoned.

-Source: The Hindu