CONTENTS

- The Truth About India’s Booming Toy Exports

- The Need to Overhaul a Semiconductor Scheme

The Truth About India’s Booming Toy Exports

Context:

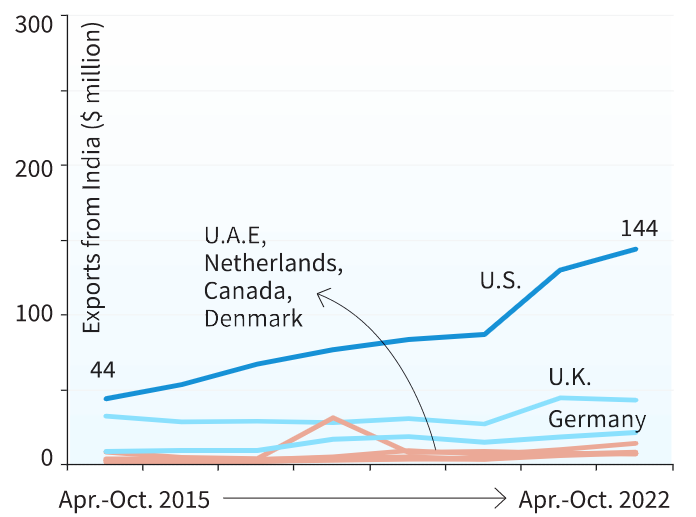

India’s toy industry, though small in scale, has been a significant topic in policy discussions spanning the era of the “permit license raj” to the current ‘Make in India’ initiative. According to a recent official press release, between 2014-15 and 2022-23, toy exports surged by 239%, while imports saw a decline of 52%, transforming India into a net exporter.

Relevance:

- GS-2 Government Policies and Interventions

- GS-3 Industrial Growth

Mains Question:

Analyse the factors that have contributed to the noteworthy turnaround in toy industry in India over the past years. Is protectionism bigger reason than an upswing in investment in achieving this feat? (15 Marks, 250 Words)

Further Studies on the Growth of India’s Toy Industry:

- An undisclosed case study sponsored by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) and conducted by the Indian Institute of Management Lucknow (IIM-L) attributes this export success to promotional efforts within the ‘Make in India’ framework, initiated since October 2014.

- While the detailed case study remains unpublished and not publicly available, we analyze official statistics to understand the potential factors behind the reported success.

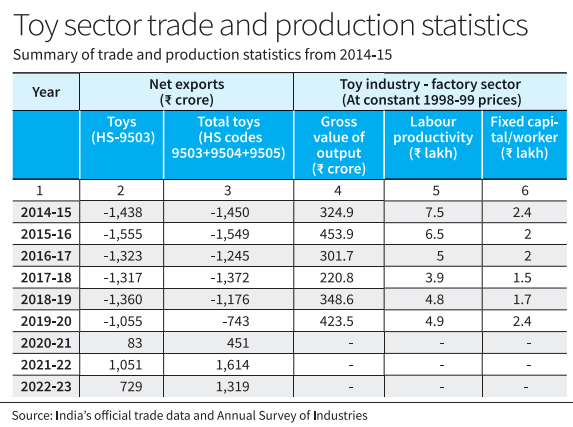

Kindly refer the table given below:

- Examining net exports (exports minus imports) of toys under HS code 9503 and total toys (HS codes 9503+9504+9505) in the table (columns 2 and 3), the trade balance was negative at ₹1,500 crore in 2014-15 but turned positive from 2020-21, marking a reversal after 23 years.

- This noteworthy turnaround in the labor-intensive industry, particularly during a period when such sectors face challenges, is undeniably commendable and makes us curious on analysing it further.

Possible Reasons Behind the Such Feats:

In essence, there are two potential reasons- protectionism or/ and a rise in investments.

Protectionism:

- An increase in import duties might decrease the demand for toys. The implementation of non-tariff barriers could constrict the supply, elevate prices, and consequently diminish demand.

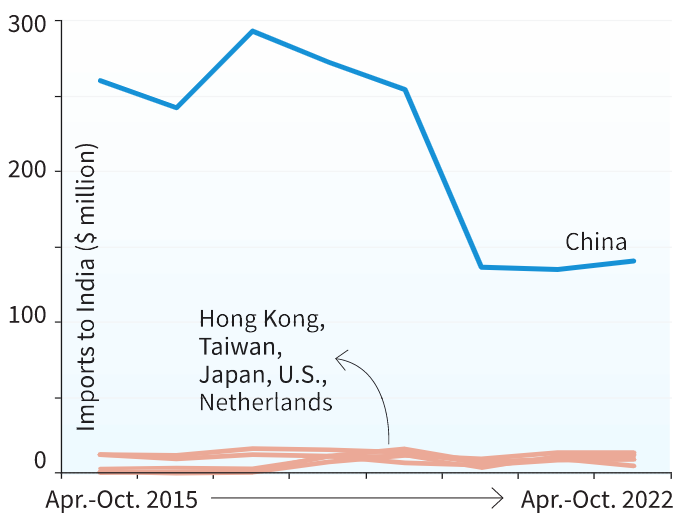

- In February 2020, customs duty on toys (HS code 9503) experienced a threefold increase from 20% to 60%.

- Starting January 2021, non-tariff barriers (NTBs), including a quality control order (QCO) and mandatory sample testing for each import consignment, were introduced, limiting imports.

- Consequently, in the fiscal year 2020-21, imports decreased, leading to a positive shift in net exports. Additionally, considering the disruptive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on global supply chains during this period, imports were adversely impacted.

- With the restoration of the global supply chain in 2022-23, net exports decreased to ₹1,319 crore from ₹1,614 crore in the preceding year for all toys, as exports moderated and imports surged.

- The decline in net exports is more pronounced (31%) for toys under HS code 9503 despite the high import duty, while it is comparatively more modest (18%) for all toys.

- Notably, in response to the renewed increase in imports, the government took further measures by raising the basic customs duty to 70% in March 2023, up from the previous rate of 60%.

Alternatively, an upswing in investments could expand capacity and enhance labor productivity, thereby boosting competitiveness and exports.

Using Data to Understand the Growth Story and Actual Reason Behind it:

Annual Survey of Industries (ASI):

Scrutinising the data from the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) spanning the years 2014-15 to 2019-20 revealed that:

- According to the most recent combined figures available for the organized and unorganized sectors in 2015-16, the organized or factory sector constituted 1% of the total number of factories and enterprises.

- It employed 20% of the workforce, utilized 63% of fixed capital, and generated 77% of the total output value.

- Over the six-year period from 2014-15, the ASI data in real terms indicate a negligible increase in fixed capital per worker and gross output value.

- Significantly, labor productivity has consistently decreased from ₹7.5 lakh per worker in 2014-15 to ₹5 lakh in 2019-20 (more recent data is not available).

- Additionally, the growth in exports during the periods pre- and post-2014-15 does not exhibit notable differences.

- Therefore, it becomes challenging to attribute India’s transition to a net toy exporter to an improvement in domestic supply and competitiveness.

- Consequently, it can reasonably be inferred that the transformation in India’s toy trade since 2020-21 is a consequence of escalating protectionist measures.

Advocating Temporary Protectionism:

- Temporary protectionism, aligning with the infant industry argument, can potentially empower domestic industries to make substantial investments, facilitate experiential learning, and improve productivity, thereby enhancing their global competitiveness.

- This protective approach should be coupled with strategic investment policies and the provision of localized, industry-specific public infrastructure.

- This combination aims to initiate a positive cycle of expanding domestic capabilities to effectively confront international competition.

- However, without these essential prerequisites, there is a legitimate concern that protectionism might become deeply rooted in the industry, leading to what Anne Krueger famously termed as “rent-seeking.” India has witnessed past instances of such policy failures.

Conclusion:

In essence, the toy industry transitioned into a net exporter since 2020-21, purportedly facilitated by ‘Make in India’ policies, as suggested by an officially sponsored research. However, as per the available industry and trade data this shift is due to the imposition of increasing tariff and non-tariff barriers. It is possible that the study conducted by IIM-L relies on different evidence to support its argument which can be revealed only when the report is made public for a meaningful policy review.

The Need to Overhaul a Semiconductor Scheme

Context:

The imminent mid-term assessment of the Semiconductor Design-Linked Incentive (DLI) scheme prompts a crucial moment for reflection. Despite its initial announcement, the DLI scheme has granted approval to only seven start-ups, significantly falling short of its ambitious target of supporting 100 start-ups over a five-year period. This impact evaluation offers policymakers a valuable opportunity to scrutinize and potentially revamp the scheme.

Relevance:

GS-2- Government Policies and Interventions

GS-3-

- Growth and Development

- Indigenization of Technology

- Industrial Policy

- Scientific Innovations and Discoveries

Mains Question:

An overhauled Semiconductor Design Linked Incentive (DLI) scheme would fortify India’s comparative advantage and augment its forays into other stages of the semiconductor global value chain. Comment. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

About Semiconductors:

- Semiconductors belong to a category of crystalline solids that exhibit electrical conductivity levels falling between those of conductors and insulators.

- These materials are widely utilized in the production of diverse electronic devices, ranging from diodes and transistors to integrated circuits.

- The compact size, reliability, energy efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of such devices contribute to their extensive use.

Semicon India Program:

- Semicon India, hosted by the India Semiconductor Mission (ISM), is an annual conference with the principal aim of fostering the expansion and advancement of the semiconductor industry in India.

- This platform serves as an opportunity for the nation to showcase its prowess in semiconductor design and manufacturing, facilitating networking and the exchange of knowledge among participants.

- India’s Semicon India Program, with a financial commitment of $10 billion, has yielded mixed results at best.

Objectives of the Program:

- Reducing dependence on semiconductor imports, especially from China, particularly in critical sectors like defense and emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence.

- Another goal is to enhance supply chain resilience by integrating into the global semiconductor value chain (GVC).

- The third objective is to leverage India’s existing strengths, as the country already hosts the design hubs of major global semiconductor industry players, with Indian chip design engineers being integral to the semiconductor GVC.

Way Forward:

- While these objectives are commendable, resource constraints necessitate a strategic approach in industrial policy to ensure maximum benefits from investments.

- Prioritizing the stimulation of the design ecosystem, which is less capital-intensive compared to the foundry and assembly stages in the semiconductor GVC, can create robust forward linkages to a burgeoning fabrication and assembly industry in India.

DLI Scheme:

Challenges Associated with the DLI Scheme:

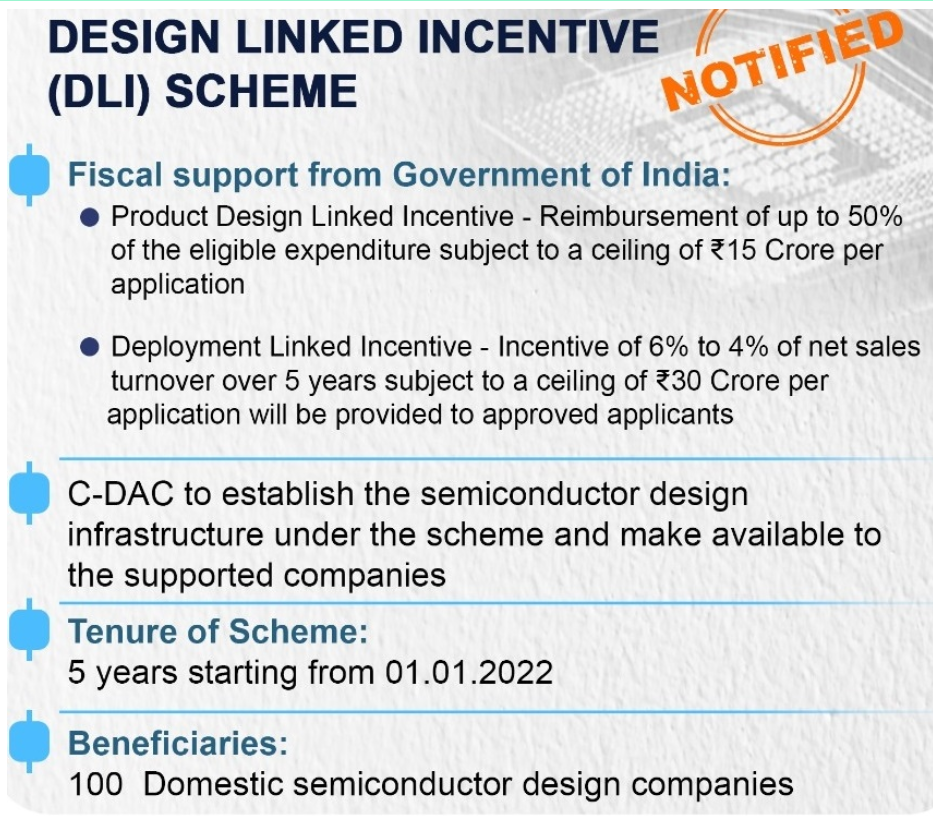

- At first glance, the Semiconductor Design-Linked Incentive (DLI) scheme seems to be well-conceived, emphasizing access to design infrastructure, including electronic design automation (EDA) tools, and providing financial subsidies for various stages of the chip design process. However, despite its apparent merits, the scheme has encountered several challenges.

- One major impediment is the requirement for beneficiary start-ups to maintain their domestic status for a minimum of three years after receiving incentives.

- Additionally, these start-ups are restricted from raising more than 50% of their necessary capital through foreign direct investment, presenting a substantial barrier.

- The high costs associated with semiconductor design start-ups pose another significant challenge.

- Semiconductor research and development typically yield results in the long term, and securing funding for chip start-ups in India remains difficult, despite promising intellectual property and business potential.

- The capital demands, coupled with the absence of success stories due to the lack of a mature start-up funding ecosystem for hardware products in India, diminish the risk appetite of domestic investors.

- Consequently, the reluctance of domestic investors to take risks may lead to a shortfall in investment for DLI beneficiary start-ups, potentially necessitating foreign equity financing, if not for the stringent ownership conditions imposed by the scheme.

Revaluation of the DLI Scheme’s Incentives and Objectives:

- The relatively modest incentives provided by the DLI scheme, capped at ₹15 Crore for Product DLI and ₹30 Crore for Deployment Linked Incentive per application, may not present a compelling trade-off for start-ups that risk losing access to essential long-term funding.

- Therefore, it becomes imperative to separate ownership considerations from semiconductor design development and adopt more startup-friendly investment guidelines.

- The primary focus of the DLI scheme should be to nurture semiconductor design capabilities within India, acknowledging that indigenous intellectual property (IP) will naturally evolve as local talent contributes to the establishment of homegrown companies over time.

- The scheme requires a revision to concentrate on the broader objective of facilitating design capabilities for a diverse range of chips within the country, as long as the entity engaged in the design development process is registered in India.

- The recent statement by the Union government emphasizing that the product should be an “India-designed chip” indicates a step in this direction. To support this policy shift, a substantial increase in the financial allocation of the scheme is necessary.

Conclusion:

A revamped approach could broaden the focus of the DLI scheme, making it more inclusive for a diverse range of semiconductor design start-ups, not just those geared for volume production. By assisting start-ups in overcoming initial challenges in developing design concepts, a recalibrated policy, guided by a capable institution, can tolerate a certain failure rate and perceive beneficiary start-ups as vehicles for exploratory risk-taking, thereby solidifying India’s presence in this high-tech sector.