CONTENTS

- Court’s Nudge on Hospital Charges, a Reform Opportunity

- Why are Unclassed Forests ‘missing’?

Court’s Nudge on Hospital Charges, a Reform Opportunity

Context:

The Supreme Court of India, during a recent hearing of a Public Interest Litigation (PIL), instructed the central government to explore methods for overseeing the pricing of medical procedures in private hospitals. This move came in response to concerns raised by the PIL regarding the high and widely varying costs of such procedures.

Relevance:

GS2- Health

Mains Question:

Affordable hospital care requires health-care financing reforms that go beyond price regulations. Comment. (10 Marks, 150 Words).

The Court’s Observation:

- The court cited the example of cataract surgeries, which cost approximately ₹10,000 in government facilities but range from ₹30,000 to ₹1,40,000 in private hospitals.

- Referring to Rule 9 of the Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010, which mandates that clinical establishments adhere to rates determined by the Central Government in consultation with State Governments, the court emphasized the need for regulation.

- It proposed using the rates set by the Central Government Health Scheme as an interim measure if the government failed to establish a regulatory framework.

Healthcare Services in India:

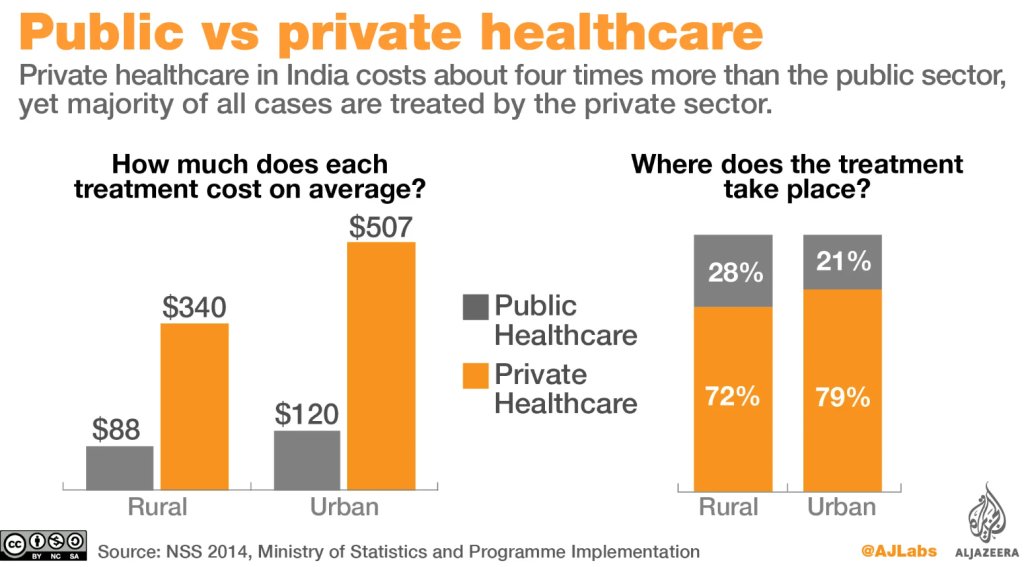

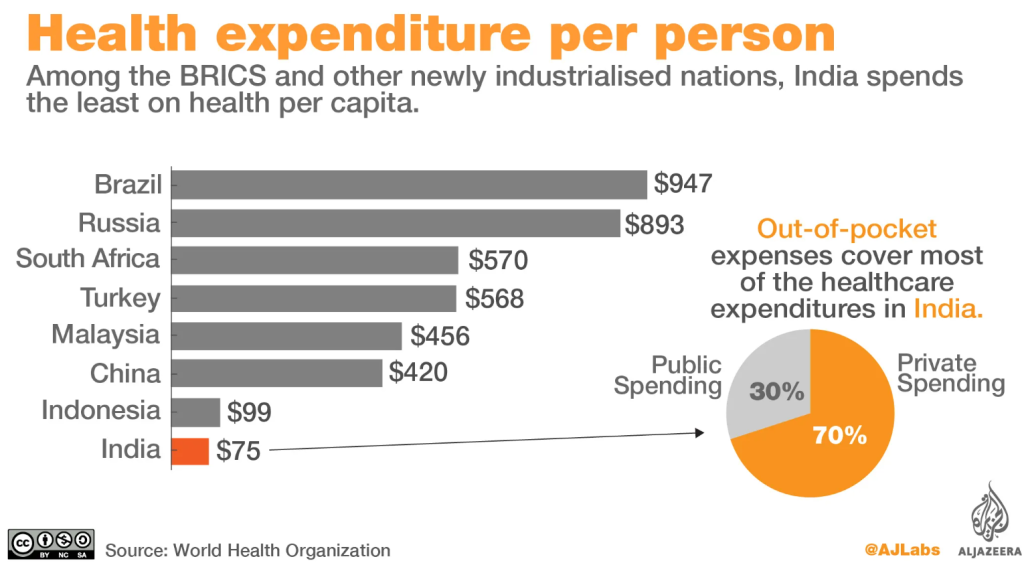

- In India, healthcare services are primarily provided by private entities, with prices determined by market forces.

- However, these markets are flawed, resulting in inefficiencies and inequalities that necessitate regulatory intervention.

- While the solution proposed by the court may oversimplify the issue, it serves as a catalyst for debate and action.

Private Healthcare Providers:

- In an unregulated market-driven environment, healthcare providers prioritize profit by charging higher prices and potentially overproviding care (known as supplier-induced demand).

- One potential solution, termed “yardstick competition,” involves regulatory bodies setting benchmark prices based on market observations.

- However, this approach encounters obstacles in India due to diverse patient demographics, unreliable price data, and inadequate regulatory structures.

- Relying solely on competition from government hospitals proves insufficient due to extended wait times, perceived service quality issues, and gaps in patient information, thus perpetuating the risk of supplier-induced demand.

Standard treatment guidelines (STGs):

- As noted by the Court, discussions regarding pricing must commence with the establishment of a benchmark for price determination. Standard treatment guidelines (STGs) can aid in defining relevant clinical needs, the nature and extent of care required, and the costs associated with all necessary inputs.

- STGs can help mitigate factors that lead to varying levels of care across different hospital procedures while allowing for clinical autonomy to address individual patient needs.

- Consequently, they facilitate the valuation of healthcare resources utilized for the precise costing of multiple procedures.

- Given the limitations of regulatory capacity, the formulation and adoption of STGs necessitate that providers’ revenues are linked to fewer payers.

- Providers should depend on reimbursements from pooled payments, which cover a significant portion of the population with minimal out-of-pocket expenses.

- With governmental support, payers and providers could negotiate pricing that ensures a reasonable and sustainable surplus beyond input costs.

- However, this progress would be impeded if healthcare providers could access markets where out-of-pocket (OOP) payments serve as an alternative or supplement to reimbursement payments.

- Several countries have achieved this challenging task through coordinated healthcare purchasing reforms, underscoring that pricing issues are systemic challenges within healthcare systems rather than merely legal or regulatory issues.

Challenges of Healthcare in India:

Implementation of Standardised Rates:

- In India, over half of the total healthcare expenditure is covered through out-of-pocket payments, while the remainder is sourced from various publicly and privately pooled funds.

- The private sector primarily comprises small-scale providers. Even if rates were standardized, their implementation would face uncertainty.

- Weak implementation mechanisms hinder effective enforcement. Command-and-control regulations utilizing pecuniary measures like price caps can swiftly influence behavior by compelling compliance.

- The suggested measures encounter significant enforcement challenges. Only 11 states and seven union territories have notified the Clinical Establishment Act, and its implementation remains weak, with scant evidence regarding its impact on affordability, care quality, and provider behavior.

- Similar limitations in design and implementation capacity have impeded the successful adoption of the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority’s decision to cap prices of stents and implants since 2017, as well as various directives mandating doctors to prescribe generic medicines.

- Standardizing rates through price caps may not effectively tackle the underlying issue of stakeholders’ misaligned incentives.

- A comprehensive healthcare financing reform strategy, informed by thorough and continuous research on appropriate procedures for formulating and adopting Standard Treatment Guidelines (STGs), must be established.

- Without this, actual pricing could be manipulated and justified in various ways. For instance, hospitals with lower average revenue per bed might increase their rates by claiming to offer superior care quality. Without STGs, verifying such claims objectively would be nearly impossible.

Data Limitations:

- Data limitations also pose a challenge. Efforts by initiatives like the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana and the Department of Health Research to develop STGs for common conditions and adopt a comprehensive costing framework have made significant progress.

- Additionally, endeavors are underway to establish an Indian version of Diagnostics-Related Groups (DRGs).

- However, the insurance industry’s initiation of STGs for hospitals in 2010 faced setbacks due to insufficient participation from private hospitals, resulting in a lack of representative and accurate costing data.

Conclusion:

This ruling presents an opportunity to develop effective processes to address a major healthcare system issue. Policies for rate standardization must be feasible, easily implemented, and adhere to established price discovery practices. Future efforts should build upon past and ongoing healthcare financing reforms, anticipate challenges, and ensure broader stakeholder involvement.

Why are Unclassed Forests ‘missing’?

Context:

In accordance with a directive from the Supreme Court dated February 19, 2024, the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) published various State Expert Committee (SEC) reports on its website earlier this April. This interim measure was initiated in response to a public interest litigation challenging the constitutionality of the Forest (Conservation) Act Amendment (FCAA) 2023. A primary concern raised in the petition was the uncertainty surrounding the status of unclassed forests, which were supposed to be identified through the SEC reports, or whether they had been identified at all.

Relevance:

GS3- Conservation

Mains Question:

Analyse the Forest (Conservation) Act Amendment (FCAA) 2023’s mandate with respect to unclassed forests. Also discuss the status of the reports of the State Expert Committees in this context. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Forest (Conservation) Act Amendment (FCAA) 2023:

- With the implementation of the FCAA, unclassed forests—previously protected under the landmark T.N. Godavarman Thirumalpad (1996) case—would lose this protection, potentially leading to their diversion.

- The SEC reports were to be compiled following the court order, which specified that ‘forests’ in accordance with their dictionary meaning and all categories of forests, regardless of ownership and notification status, would fall under the purview of the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980.

- Consequently, unclassed forests, also referred to as deemed forests, would require approval from the Central government if a project proponent sought to divert that land for non-forest purposes.

- Unclassed or deemed forests may be under the ownership of forest departments, revenue departments, railways, other government entities, community forests, or private ownership, but they are not formally notified as forests.

Have these Forests been Identified?

- The status of the reports remained unknown from 1996 until they gained attention again when the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) informed a Joint Parliamentary Committee that the State Expert Committees (SECs) had indeed identified unclassed forests, which had been duly recorded.

- This statement came in response to criticism that the proposed law undermined the Godavarman judgment and would exclude all unclassed forest land from its scope. The MoEFCC assured the Committee that “the amended Act would be applicable” to the unclassed forests identified by the SECs.

- However, in response to a Right to Information (RTI) application filed on January 17, the MoEFCC stated that it “did not have the requisite reports”.

- Although the MoEFCC has now made the SEC reports available on its website, they paint a bleak picture: no state has provided verifiable data on the identification, status, and location of unclassed forests.

- In fact, seven states and union territories—Goa, Haryana, Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh, Lakshadweep, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal—appear not to have formed SECs at all.

- While twenty-three states have shared their reports, only seventeen are in accordance with the directives of the Court.

- Many states have cited the one-month timeframe provided by the Supreme Court as too short, and have stated that “the nature of work [is] voluminous”. As a result, they have not conducted physical cadastral surveys or demarcation of unclassed forest lands.

What Information do the Reports Contain?

- Only nine states have provided details regarding the extent of unclassed forests. The majority of states and UTs have merely disclosed the extent of various types of forest areas as outlined in the directive, typically those under government ownership, categorized as either forest or revenue land, and occasionally under other government departments.

- Additionally, almost no state or UT has specified the geographical locations of forests. Any geographic information provided pertains solely to reserve or protected forests, which is redundant since such data is already available to Forest Departments.

- Furthermore, the SEC reports cast doubt on the accuracy of the Forest Survey of India‘s findings, the sole government agency responsible for surveying and assessing forests.

- For instance, Gujarat’s SEC report indicates its unclassed forests cover 192.24 sq. km, whereas the Survey reported a substantially higher figure of 4,577 sq. km (for the period 1995-1999).

- The reliance on SECs without on-the-ground verification is likely to have led to widespread deforestation of areas that should have been identified, demarcated, and protected 27 years ago.

- However, due to the absence of baseline data from 1996-1997, the extent of lost unclassed forest remains unknown. For instance, Kerala’s SEC omitted the Pallivasal unreserve, an ecologically fragile area in Munnar, which also suffered significant damage during the floods in 2018.

- The potential loss of such forests is likely to be a recurring issue across all states and warrants further investigation.

- It is evident that the reports were hastily compiled, utilizing incomplete and unverified data gathered from easily accessible records, and submitted to the Supreme Court merely to fulfill their obligations.

- The Godavarman order of the Supreme Court was supposed to be implemented meticulously. The failure to do so represents a missed opportunity to fulfill the requirements of the Indian Forest Policy, which aims for 33.3% forest cover in plains and 66.6% in hills.

Conclusion:

Enacting the FCAA without thoroughly examining the SEC reports reflects a lack of diligence on the part of the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and will have repercussions for India’s ecosystems and ecological security. Those accountable for this oversight must be held responsible, and the national government should take corrective measures to reassess, reclaim, and safeguard forest areas in accordance with the 1996 judgment.