Why is this in news?

- WHO released its Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) 2025 report in mid-October 2025.

- India identified as one of the worst AMR hotspots globally.

- Highlights a severe rise in antibiotic-resistant infections, especially in ICUs.

- Kerala’s progress and India’s slow national AMR implementation reignited policy debates.

- Published just ahead of World AMR Awareness Week (18–24 November).

Relevance

- GS 3 – Science & Technology / Biotechnology

Antimicrobial resistance, global surveillance systems (GLASS) - GS 3 – Health & Disease Burden

AMR as a major public health threat; ICU infections; One Health approach - GS 3 – Environment

Pharma effluent regulation, environmental determinants of AMR

Basics

- Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve to resist antibiotics → infections become harder or impossible to treat.

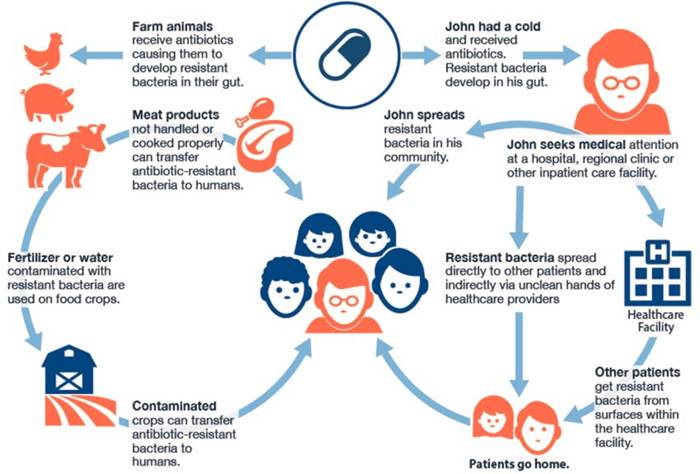

- AMR is driven by human, animal, agriculture, and environmental pathways → a One Health problem.

- GLASS is WHO’s global AMR monitoring system, operational in 100+ countries; India joined in 2017.

Key global findings (GLASS 2025)

- 1 in 6 infections globally resistant to commonly used antibiotics.

- South-East Asia shows the steepest rise; India is disproportionately affected.

- High resistance among critical pathogens: E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus.

- WHO flags a modest but insufficient improvement in the global antibiotic development pipeline.

India-specific findings

- 1 in 3 infections in India in 2023 were antibiotic-resistant.

- Highest resistance burden in ICUs for E. coli, Klebsiella, and MRSA.

- Strong AMR drivers in India:

- Over-the-counter antibiotics

- Self-medication and incomplete courses

- Contaminated pharma effluents and hospital waste

- Weak enforcement of antibiotic regulations

- GLASS notes progress but flags underfunding, uneven surveillance, and weak coordination.

Current efforts in India

- National Programme on AMR Containment.

- ICMR’s AMRSN / i-AMRSS network.

- NCDC’s NARS-Net.

- 2019 ban on colistin in animal feed (significant but long-term impact).

Major weaknesses identified

- Surveillance bias:

- Overdependence on tertiary hospitals → overestimation of AMR; weak data from rural/primary-care settings.

- Underfunding:

- No long-term investment in AMR research, stewardship, or diagnostics.

- Poor One Health coordination.

- NAP-AMR implementation slow:

- 2017 plan remains mostly unexecuted in many States.

- Public awareness extremely low → AMR remains an abstract concept for most Indians.

Expert assessments

Abdul Ghafur

- India’s AMR levels are among the highest globally.

- True national estimates require integrating 500+ NABL labs + primary/secondary hospital microbiology.

V. Ramasubramanian

- Surveillance centres must be geographically spread; without regional representation, conclusions are distorted.

Ella Balasa

- Public needs relatable narratives; humanising AMR is essential for behavioural change.

Antibiotic development pipeline (critical analysis)

Global pipeline trends

- WHO 2024 pipeline report:

- 97 candidates in clinical & preclinical stages (up from 80 in 2021).

- Only 12 of 32 traditional antibiotics are innovative (new class or new mechanism).

- Just 4 candidates target WHO priority MDR Gram-negative pathogens.

India’s status

- CDSCO has approved four new antibiotic candidates in the last two years.

- Six more have global approval.

Limitations

- Pipeline is still too small to address global AMR.

- Limited innovation; low access in LMICs.

- Most new drugs do not target carbapenem-resistant Gram-negatives.

Features needed in next-generation antibiotics

- New mechanisms bypassing current resistance.

- Dual formulations (IV + oral).

- Activity against highest-priority MDR pathogens.

- Safe, affordable, and aligned with stewardship guidelines.

- Low likelihood of inducing further resistance.

Global and industry-side initiatives

AMR Industry Alliance

- Promotes development of new antibiotics and diagnostics.

- Supports responsible antibiotic manufacturing.

- Works on equitable access, especially in LMICs.

Funding gaps

- Surveillance and innovation receive intermittent and inadequate funding.

- Need sustained national investment in AMR research, stewardship, and public awareness.

Kerala model

- Only State with a fully operational AMR State Action Plan.

- Kerala AMR Strategic Action Plan (2018) adopts a strong One Health model.

- AMRITH (2024) stops over-the-counter antibiotic sales.

- State antibiogram shows a slight reduction in AMR levels.

- Goal: antibiotic-literate Kerala by December 2025.

Other significant interventions

- 2019 colistin ban in poultry/livestock → expected long-term benefits.

- Need uniform enforcement across all States.

What India must do (priority recommendations)

Surveillance

- Build a representative national network using NABL labs.

- Strengthen microbiology capacity in district and primary-care hospitals.

Stewardship

- Nationwide ban on OTC antibiotic sales.

- Standardised antibiotic guidelines across hospitals.

- Functional stewardship committees in all tertiary and secondary facilities.

Environment

- Regulate pharma effluents and medical waste.

- Mandatory antimicrobial pollutant monitoring.

Awareness

- Large-scale community orientation on AMR.

- Humanised public campaigns (schools, digital media).

Innovation

- Incentives for new antibiotic classes.

- Academia-industry collaborations.

- Public funding for early-stage R&D.

Governance

- Accelerate implementation of NAP-AMR (2017).

- Strong State-level monitoring and coordination.

Conclusion

- India’s AMR crisis is severe, escalating, and under-monitored.GLASS 2025 reinforces that resistance is rising faster than countermeasures, and progress remains fragmented.

Kerala demonstrates that structured One Health interventions, regulatory enforcement, and public literacy can reduce resistance trends. - India now needs integrated surveillance, strict stewardship, environmental control, innovation incentives, and long-term funding to prevent a future where routine infections again become untreatable.