Historical Background: The Basis of the Border

- Manchu Rule (1644–1911):

- Two major maps drawn with European Jesuit assistance:

- Kang-hsi Map (1721): Tibet-Assam segment; Tibet considered only up to the Himalayas; Tawang (south of Himalayas) not Tibetan.

- Ch’ien-lung Map (1761): Eastern Turkestan-Kashmir segment; Eastern Turkestan not conceived as trans-Kunlun; southern desolate region not claimed.

- Two major maps drawn with European Jesuit assistance:

- 1913–14 Simla Conference:

- RoC delegate accepted non-Tibetan tribal belt (present Arunachal Pradesh) was not Tibetan.

- India included it in Assam; outcome consistent with Kang-hsi’s map.

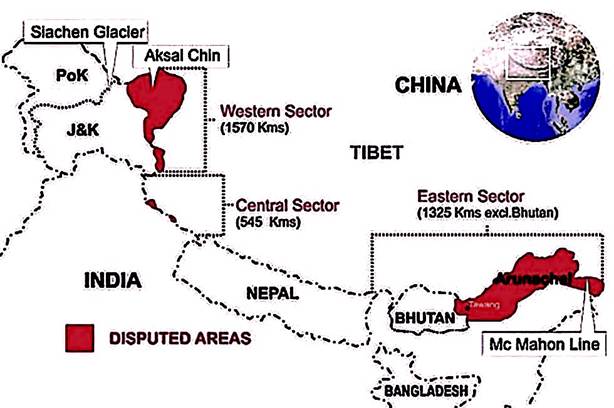

- Implication: Traditional Chinese claims were limited; historical maps did not support trans-Himalayan claims in Arunachal Pradesh or Aksai Chin.

Relevance:

- GS II (International Relations & Security): India-China boundary disputes, historical treaties, diplomatic negotiations.

- GS I (Geography & History): Geopolitical importance of Arunachal Pradesh and Aksai Chin, historical mapping.

- GS III (Security): Strategic implications of border management, principle-based negotiation, territorial sovereignty.

Evolution of Chinese Claims

- 1943: RoC sets aside Manchu maps; claims large Indian territories during WWII.

- Justification: map described as “unprecise draft.”

- December 1947: Similar map used amid India-Pakistan conflict.

- Pattern: China inherited and expanded claim-making from predecessor regimes rather than based on historical precedent.

Post-Independence Diplomacy

- 1960 Talks (Jawaharlal Nehru & Chou En-lai):

- Chou questioned India’s historical evidence, using semantic and rhetorical tactics.

- Proposed resolving the boundary not solely on maps, but via principles: equitable, reasonable, dignity-preserving “package deal.”

- Key Insight (Vijay Gokhale, The Long Game):

- Chou avoided suggesting territorial swap (Aksai Chin ↔ Arunachal Pradesh).

- Both sides aimed for comprehensive resolution, integrating boundary, geopolitical, and trade matters.

Specific Boundary Alignments

- 1914 Alignment: Indo-Tibetan boundary in line with Kang-hsi map; acknowledged by both parties at the time.

- 1899 Alignment: Kashmir-Sinkiang boundary line; based on watershed principle; related to Aksai Chin.

Core Principles for Resolution

- Equity & Respect: No defeat to either side; preserve dignity and self-respect.

- Historical Evidence: Manchu-era maps provide strongest evidence for India’s claims.

- Geopolitical Package Approach: Consider boundary settlement along with trade and security issues; possibility of territorial swap remains contingent on mutual security needs.

Key Takeaways

- Historical maps favor India: Manchu-era records clearly delineate Tibet’s southern boundary and Aksai Chin claims.

- China’s modern claims: Largely political opportunism during moments of Indian vulnerability; not supported by historical documentation.

- Diplomatic complexity: Both sides acknowledge need for principles beyond maps to achieve a sustainable, dignified settlement.

- Strategic perspective: India must maintain historical evidence, assert sovereignty, and engage in principle-based negotiations while safeguarding national security.