Contents

- Time for India and Nepal to make up

- Committee for Reforms in Criminal Law: Colonial or Decolonial

- Minimum age of marriage for women: Make it Same

TIME FOR INDIA AND NEPAL TO MAKE UP

Focus: GS-II International Relations

Introduction

- When the Nepal-India dispute over the Himalayan territory of Limpiyadhura (Kalapani row) flared up, a series of events involving: Indian media coverage of Nepal, Accusation of Nepal acting under Chinese influence, Nepalese questioning of India’s commitment to ‘satyameva jayate’, Nepal’s claim that the true birthplace of Lord Ram was situated in present-day Nepal, etc., have put the India-Nepal relations under a lot of avoidable strain.

- De-escalation must happen before the social, cultural and economic flows across the open border suffer long-term damage.

Click Here to read more about the Kalapani Row

The Cause

- The cause of the split that has opened up between Kathmandu and Delhi relates to the disputed ownership of the triangle north of Kumaon, including the Limpiyadhura ridgeline, the high pass into Tibet at Lipu Lek, and the Kalapani area hosting an Indian Army garrison.

- New Delhi’s position on the dispute is based on its decades-long possession of the territory, coupled with Kathmandu’s implied acquiescence through its silence and the omission of Limpiyadhura on its own official maps.

- Nepal’s claim is centred on the Treaty of Sugauli (1815), whose language reads the “Rajah of Nipal renounces all claim to the countries lying to the west of the River Kali”.

History of administration

- Land records were kept in Nepal’s district headquarters of Darchula and Baitadi until access was blocked in the 1960s by the Indian base at Kalapani.

- Kathmandu responded with sensitivity to Indian strategic concerns before and after the 1962 China-India war by allowing the Indian army post to be stationed within what was clearly its territory at Kalapani and not publicly demanding its withdrawal.

Road to Lipu Lek

- A border demarcation team was able to delineate 98% of the 1,751 km Nepal-India frontier, but not Susta along the Gandaki flats and the upper tracts of the Kali.

- It was after India published its new political map in November following the bifurcation of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh that the pressure arose for Kathmandu to put out its own map incorporating the Limpiyadhura finger.

Way forward: Dousing the volcano

- The ice was broken on August 15 when Nepali Prime Minister Oli called the Indian Prime Minister on the occasion of India’s Independence Day, but that is just the beginning.

- Talks must be held, for which the video conference facility that has existed between the two Foreign Secretaries must be re-activated.

- Delay will wound the people of Nepal socially, culturally and economically, and it will also hurt Indian citizens from Purvanchal to Bihar and Odisha, who rely on substantial remittance from Nepal.

- India does have experience of successfully resolving territorial disputes with Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and even Pakistan bilaterally and through third-party adjudication. Given political will at the topmost level, it should be possible to douse the Limpiyadhura issue very quickly.

- While India’s Foreign Office has thankfully remained restrained in its statements, India is required to maintain status quo in the disputed area.

- One difficulty is the apparent absence of backchannel diplomacy between the two capitals, which helped in ending the 2015 blockade.

-Source: The Hindu

COMMITTEE FOR REFORMS IN CRIMINAL LAW: COLONIAL OR DECOLONIAL

Focus: GS-II Governance

Why in news?

- The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) constituted the Committee for Reforms in Criminal Law to undo the “colonial foundations of our criminal law”.

- The precise mandate of the Committee has not been put into the public.

- Reforms based on the Committee’s recommendations will have serious ramifications for every person who is subjected to the criminal justice system.

Introduction

- A smoothly functioning legal system determines our freedom to live authentic lives as full citizens in a democratic polity.

- Decolonisation is an ongoing process, which requires a commitment to undoing the colonial logic of domination governing citizen-state relations.

Concerns – Disabling Participation

Internet for Participation

- The Committee’s procedures are designed to disable broad-based participation.

- The exclusive route to participation is the Committee’s website.

- However, only about 40% of the population actively uses the Internet.

- Internet usage itself is linked to structural barriers – like women are less likely to have Internet access; and in Kashmir, Internet services are suspended.

Usage of English

- All the Committee’s documentation and background resources, including 89 reports of the Law Commission of India (LCI), are in English.

- The most reliable estimates suggest that only 10% of the Indian population speaks English, and most such persons reside in urban areas.

Pandemic time limitation

- The life cycle of the Committee coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic.

- With several marginalised groups struggling to secure even rudimentary healthcare, education and employment during the harsh times of the Pandemic, it is inconceivable that they could participate meaningfully in a reform exercise of this scale at this moment in time.

Lack of representation

- There appears to be no representation on the Committee from subaltern caste, gender, sexual, or religious groups.

- There are no members on the Committee based outside of a limited geographic region in north India.

- It is crucial for a Committee tasked with transforming criminal justice to be more representative.

- It must include members who can speak to the experience of the many publics governed by the criminal law.

Current Situation of oppression

Oppressed communities across India are over-policed and under-protected.

- Religious minorities as well as the impoverished Dalit and Adivasi communities bear the brunt of criminal laws through police violence, long periods of undertrial detention, harsh punishments and poor legal representation.

- Women, transgender people, and sexual minorities, who overwhelmingly experience gender-based violence, are frequently let down by the criminal justice system.

- The Committee’s composition and operation render democratic participation from these groups impossible.

Concerns – Disabling deliberation

- There is nothing to explain why an ad hoc Committee was set up for a task of this relevance and magnitude when such questions of law reform are typically entrusted to the LCI, which has established procedures to ensure inclusion and transparency.

- The Committee has not undertaken to publish the representations it receives from the public during its consultation process.

- There are no published Terms of Reference.

- There can be no contestation, debate or deliberation without the Committee communicating openly and honestly with all its interlocutors.

- The Committee is carrying out consultations from July to October 2020, and within three months, respondents are expected to form and articulate reasoned opinions on almost every conceivable issue of criminal law, procedure or evidence.

Deliberative democracy

- A deliberative vision of democracy requires that all members of society are able to participate in collective decision-making, and that decision-making takes place through reasoned deliberation.

- It recognises that participation in political processes is hindered by structural inequalities produced by interlocking systems of oppression, including caste, patriarchy, disablism and communalism.

- As a response to these hierarchies, deliberative democracy requires that everyone participates in decision-making by giving reasons for why they prefer a particular course of action.

- This reasoning must be made publicly available for others to contest.

- Where political decision-making takes place in an open and transparent manner, oppressed groups can influence it through the strength of their reasons.

- This can mitigate the extent to which a lack of economic, social or political power will otherwise compromise their participation.

- An inclusive, transparent and meaningful public consultation process for law-making is one practical way to implement a deliberative version of democracy.

-Source: The Hindu

MINIMUM AGE OF MARRIAGE FOR WOMEN: MAKE IT SAME

Focus: GS-II Social Justice

Introduction

- The government’s decision to reconsider the minimum age of marriage for women is a step welcomed by many.

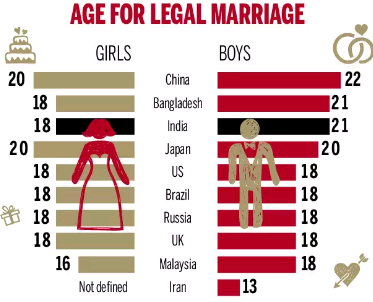

- Currently pegged at 18 years for women and 21 for men, the minimum age of marriage is a product of personal laws that mostly do not have equal rights for women.

- For Hindu women, the change from child marriage being a norm to outlawing it has been an arduous fight against religious and social conservatives.

How age limits came to be where they are now?

- The Indian Penal Code in 1860 criminalised sexual intercourse with a girl below the age of 10, introducing the first legal framework for a minimum age of consent for girls.

- Increasing the age by even just two years to 12 in the Age of Consent Bill in 1927 was opposed by many nationalists who saw the move as imperial interference with local customs.

- In 1929, the barrier was further raised to outlaw marriage of girls below 16.

- From then, it took nearly five decades to bring the law to its current standard of 18 years for women and 21 for men.

Reasoning

There are two crucial reasons that make it necessary to update the law again:

I- Improve Female Health

- According to a United Nations Population Fund report, India is home to one in three child brides in the world.

- Early marriages causing early pregnancies are inherently linked to higher rates of malnourishment, maternal and infant mortality.

- Although maternal mortality rate has been declining, the move to increase the minimum age of marriage could boost the fight.

II- Keeping up the promise of equality made to women under the Constitution

- There is no reason why the law makes the presumption that the minimum age of marriage must be different for men and women.

- It perpetuates benevolent sexism or the stereotype that women are more mature and therefore, can be given greater responsibilities at a younger age in comparison to men.

- The reflection of patriarchy in personal laws must change to fit the framework of the Constitution.

Conclusion

- Despite the well-intended reasons, a change in law may not suffice in ending discrimination against women.

- Policymakers will do well to delink age of marriage and age of sexual consent as teen pregnancies happen outside of marriage too.

- Laws that prevent child marriages and sexual exploitation of minors must be implemented effectively.

- Without improving other welfare mechanisms including educational and employment opportunities for women, the increase in age of marriage will only delay the problem and not remedy it.

-Source: Indian Express