CONTENTS

- Revised Criminal Law Bills

- Places of Worship Act, 1991 must be Reviewed

Revised Criminal Law Bills

Context:

In the current parliamentary session, more than 140 members were absent when the three Bills, replacing India’s criminal laws, were passed. Creating laws without a significant presence of Opposition members reflects poorly on the legislative process. Many concerns related to the bills could not be addressed in Parliament due to the absence of a significant number of members.

Relevance:

GS2- Government Policies & Interventions

Mains Question:

The new criminal laws have favorable aspects, but they do not introduce any groundbreaking alterations in India’s Criminal Justice System. Comment. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Background:

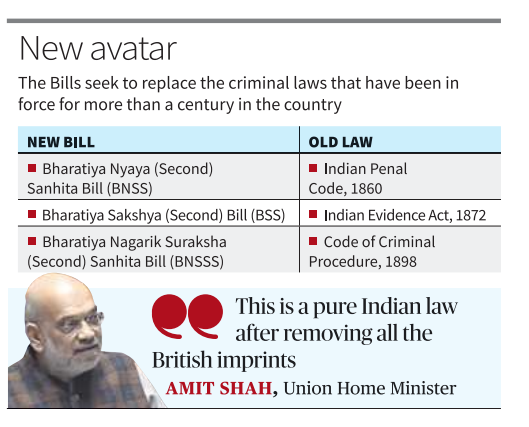

- These bills, namely the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (replacing the IPC), the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (replacing the CrPC), and the Bharatiya Sakshya Bill (replacing the Evidence Act), underwent scrutiny by a Parliamentary Standing Committee before being introduced.

- However, despite this scrutiny, they still required thorough legislative discussions in the full chambers due to their wide-ranging implications for the entire nation.

On the Revised Codes:

A notable feature of the new codes is that, apart from a reordering of sections, much of the language and content of the original laws has been retained.

- The Bharatiya Nyaya (Second) Sanhita Bill, 2023, has incorporated the definition of a ‘terrorist act’ from the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), specifically adopting Section 15 of the UAPA.

- This UAPA definition identifies a terrorist act as any action intending to threaten the unity, integrity, security, economic security, or sovereignty of India, or to instill terror in the people.

- The revised Bill aligns with the UAPA but expands the definition to include activities related to counterfeit Indian currency or material.

- The new Bill introduces the offense of possessing property derived from a terrorist act, punishable if held knowingly. Similarly, harboring a terrorist is punishable if done both voluntarily and knowingly.

- The Bill also includes the offense of recruiting and training individuals for terrorist acts, mirroring sections 18A and 18B of the UAPA.

- Notably, an officer, not below the rank of Superintendent of Police, can decide whether to continue prosecuting a terrorist act under the UAPA or the new Bill.

- Punishment for a terrorist act is death or life imprisonment, while those conspiring, abetting, inciting, or facilitating such acts may face imprisonment ranging from five years to life.

- The revised Bill adds a definition of “cruelty” against a woman by her husband and relatives, punishable with up to three years in jail.

- It defines cruelty as willful conduct likely to drive a woman to suicide, cause grave injury, or coerce her to meet an unlawful demand for property or valuable security.

- A new provision stipulates that unauthorized publication of court proceedings related to rape or sexual assault cases without permission is punishable by a two-year jail term and a fine. However, reports on High Court or Supreme Court judgments do not fall under this provision.

- The term ‘mental illness’ in the original Bill has been replaced with ‘unsoundness of mind,’ addressing concerns about the broad scope of the former. The revised Bill also includes the term ‘intellectual disability’ in section 367.

- Mob lynching, initially categorized as a separate offense, is now penalized on par with murder, removing the minimum seven-year sentence from the original Bill.

- Recommendations to criminalize adultery and non-consensual sex between individuals of the same gender have been excluded from the revised Bill.

- The definition of ‘petty organized crime’ has been refined to specify offenses committed by a group or gang, such as theft, snatching, cheating, unauthorized selling of tickets, unauthorized betting or gambling, and selling of public examination question papers.

- On the procedural front, some commendable features include the provision for First Information Reports (FIRs) to be registered by a police officer regardless of where the offense occurred, and efforts to promote the use of forensics in investigations along with the documentation of searches and seizures through videography.

- In the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha (Second) Sanhita, 2023, the concept of ‘community service’ as a form of punishment for minor offenses has been defined.

- Handcuffing is permitted beyond the arrest stage, and court proceedings can be conducted through audio-visual means.

- The revised Bill does not address concerns about allowing police custody beyond the initial 15 days of arrest, potentially leading to misuse.

- Preventive detention powers now include a strict timeline, requiring the detained person to be produced before a Magistrate or released within 24 hours.

- In the Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Bill, 2023, the admissibility of electronic evidence is subject to section 63, aligning with the requirement for a certificate under section 65B of the Indian Evidence Act.

Associated Shortcomings:

- Contrary to Union Home Minister assertion that the colonial imprint of the IPC, CrPC, and the Evidence Act has been replaced by a purely Indian legal framework, the new codes do not bring about groundbreaking changes in the policing system, crime investigation, and the conduct of prolonged trials in the country.

- There is uncertainty regarding the inclusion of ‘terrorism’ in the general penal law when it is already punishable under special legislation. Serious charges such as terrorism should not be invoked lightly.

- A significant shortcoming is the failure to clarify whether the new criminal procedure allows police custody beyond the 15-day limit, or if it is merely a provision allowing the 15-day period to extend across any days within the first 40 or 60 days following a person’s arrest.

Conclusion:

The new laws have favorable aspects, but they do not introduce any groundbreaking alterations. It is crucial to recognize that revisions in the law should be guided by a vision for a legal framework that addresses all the deficiencies in the criminal justice system.

Places of Worship Act, 1991 must be Reviewed

Context:

The recent approval by the Allahabad High Court for a survey of the Shahi Eidgah in Mathura has reignited a longstanding debate on the Places of Worship Act of 1991. Similar disputes, reminiscent of the Varanasi Gyanvapi case, have emerged in different parts of the country.

Relevance:

GS-2

- Government Policies and Interventions

- Judiciary

- Indian Constitution

Mains Question:

The Places of Worship Act, as a legislative instrument, must evolve to meet the challenges of the present while honouring the historical tapestry. Discuss. (10 Marks, 150 Words).

Recent Developments:

- Hindu organizations have filed petitions to offer prayers at various locations, including the Quwwatul Islam mosque in Delhi, claiming the Taj Mahal as the Tajo Mahal temple, and demanding access to specific areas in Mangaluru.

- The Allahabad High Court’s decision to allow a survey of the Shahi Eidgah in Mathura has set a precedent for similar disputes across the country.

- The survey, similar to the one ordered for the Gyanvapi mosque in Varanasi, aims to verify claims made by Hindutva groups regarding the historical positioning of these places of worship.

- The legal landscape is further complicated by numerous cases and petitions in various courts, including eighteen pleas in Mathura alone seeking ownership of disputed land by the temple management.

- These legal battles highlight a growing trend where Hindu groups seek ownership of land where mosques are situated, challenging the Places of Worship Act and placing the government and judiciary in a challenging position.

Places of Worship Act, 1991:

- Enacted in the aftermath of the Ram Janmabhoomi Movement, the Places of Worship Act has played a crucial role in maintaining religious harmony.

- The Act, passed in 1991, aims to preserve the religious status quo by freezing the state of all places of worship as of August 15, 1947, with the exception of the Ayodhya dispute.

- It was legislated with the purpose of maintaining the status of religious places of worship as they existed on August 15, 1947. The law prohibits the conversion of any place of worship and ensures the preservation of its religious identity.

Key Provisions of the Act:

Prohibition of Conversion (Section 3):

Prevents the conversion of a place of worship, either in full or in part, from one religious denomination to another or within the same denomination.

Maintenance of Religious Character (Section 4(1)):

Ensures that the religious identity of a place of worship remains unchanged from what it was on August 15, 1947.

Abatement of Pending Cases (Section 4(2)):

Declares that any ongoing legal proceedings related to the conversion of a place of worship’s religious character before August 15, 1947, will be terminated, and no new cases can be initiated.

Exceptions to the Act (Section 5):

- Excludes ancient and historical monuments, archaeological sites, and remains covered by the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958.

- Does not apply to cases already settled or resolved, disputes resolved by mutual agreement, or conversions that occurred before the Act came into effect.

- Specifically excludes the place of worship known as Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, along with any associated legal proceedings.

Penalties (Section 6):

- Specifies penalties, including a maximum imprisonment term of three years and fines, for violations of the Act.

- Recent disputes in Mathura and Varanasi involve litigants invoking the 1991 Act, emphasizing its role in protecting the sanctity of religious places.

Shortcomings in the Act:

- Critics argue that freezing the religious character of places of worship at a specific historical moment may not account for the evolving social fabric and religious demographics of the nation over time.

- Additionally, the Act faces criticism for its perceived inability to address disputes arising from historical grievances, such as the alleged demolition of temples during medieval times.

- The Union Government’s reluctance to clearly articulate its stance on the Places of Worship Act adds to the complexity of the situation.

- The lack of a definitive position raises concerns about the government’s commitment to either uphold, review, or scrap the legislation, contributing to confusion surrounding its applicability in present times.

- Critics contend that the Act hinders judicial review, a fundamental aspect of the Constitution, thereby undermining the checks and balances system and restricting the judiciary’s role in safeguarding constitutional rights.

- Detractors criticize the Act for employing an arbitrary date (Independence Day, 1947) to determine the status of religious places. They argue that this cutoff date neglects historical injustices and denies redressal for encroachments that occurred before that specified date.

- Opponents claim that the Act encroaches upon the religious rights of Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, and Sikhs. They assert that it impedes their ability to reclaim and restore their places of worship, thereby restricting their freedom to practice their religion.

- Critics argue that the Act runs counter to the principle of secularism, a core component of the Constitution, by seemingly favoring one community over others.

- Detractors specifically criticize the Act for excluding the land involved in the Ayodhya dispute. They question its consistency and raise concerns about the differential treatment of religious sites, pointing to potential inconsistencies in its application.

Way Forward:

- To prevent further deterioration of the situation and potential communal tensions, the government must provide clarity on its position regarding the Places of Worship Act.

- The Supreme Court, as the ultimate arbiter, must expedite proceedings on the validity and interpretation of the Act in the context of evolving disputes.

- The nation faces far-reaching consequences if these issues are left unaddressed. The legal ambiguity surrounding the Places of Worship Act could lead to the reemergence of similar disputes, compromising social harmony.

- A proactive approach from both the government and the judiciary is essential for a swift resolution.

- As the legal complexities unfold, striking a balance between historical grievances and maintaining communal harmony becomes paramount.

- The Places of Worship Act, while well-intentioned, needs careful reevaluation to address contemporary challenges and ensure its continued relevance in a dynamically evolving society. A judicious resolution that upholds principles of justice, fairness, and social cohesion is awaited.

- In navigating these intricate contours, it is crucial to recognize that the preservation of religious harmony and historical justice need not be mutually exclusive. A nuanced and inclusive approach is required to address contemporary challenges while honoring the diverse tapestry of India’s cultural and religious heritage.

Conclusion:

The Places of Worship Act must evolve to meet present challenges while respecting the historical tapestry that defines the nation. Only through a harmonious blend of legal clarity, historical understanding, and a commitment to social cohesion can a future be ensured where places of worship stand as symbols of unity rather than sources of division.